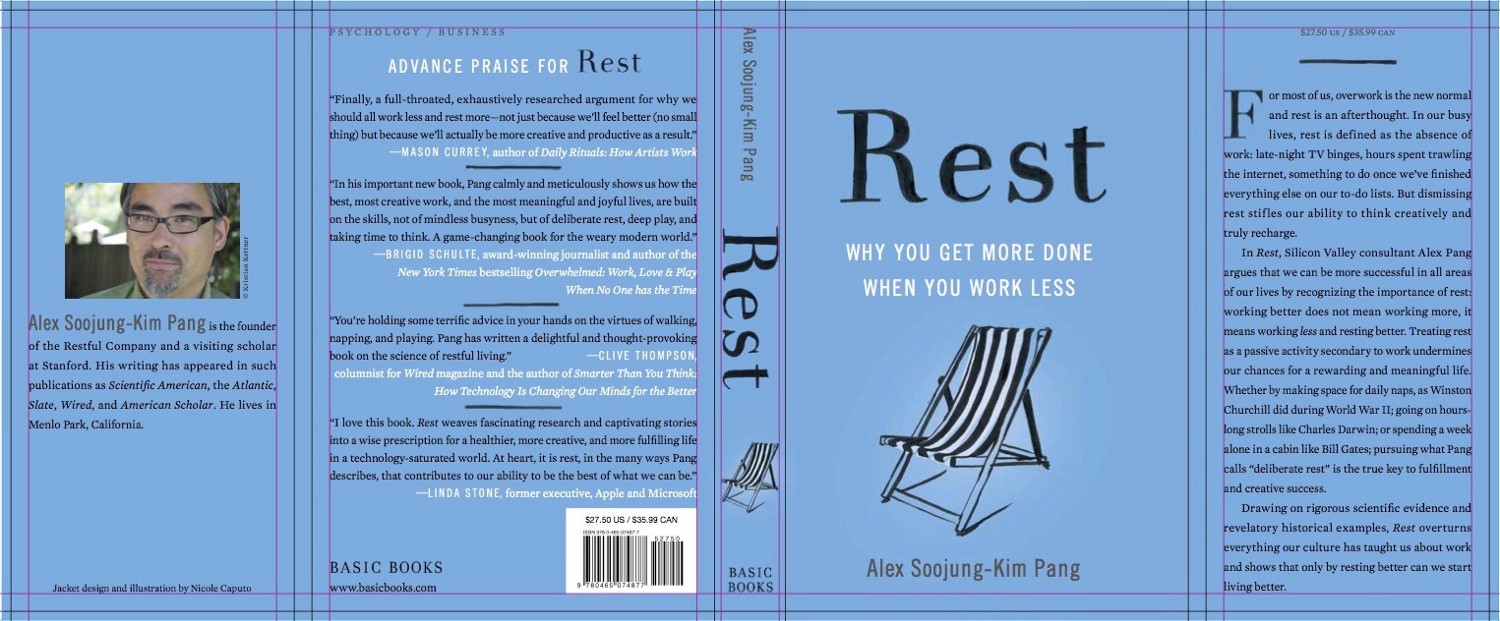

Recently I was in Amsterdam to promote the Dutch edition of my new book, Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less. (If you read Dutch, you can order the translation.) The book argues that we underestimate the importance of rest in our busy lives; that we should see work and rest as partners, not competitors; and that some of history’s most accomplished figures learned to rest in ways that helped them be more creative.

In addition to a round of press interviews and two photo shoots (a novel and slightly surreal experience), I gave a lecture about rest at the Westerkerk, a church in Amsterdam. Without realizing it, the School of Life, which had organized the talk, had chosen a perfect venue to illustrate my central argument.

The Westerkerk (the name translates as “Western Church”) was built in the 1620s by Dutch Protestants who wanted a church designed for Protestant services. The building is at once impressive and understated, grand in scale but unadorned, and can easily fit hundreds of people. Just outside the church doors is the Prinsengracht, one of Amsterdam’s famous canals; it was actually still being completed when the Westerkerk was under construction. The busy Westermarkt is just across the street.

In other words, the location is bustling, not bucolic. Had you come to services here after the church opened in 1631, you would have passed workmen, threaded your way around construction projects, stepped around bales of cargo and stalls hawking goods from across Europe. Looking up, you’d have seen the church’s grand tower; but the masts of ships returning from voyages to the East Indes, their holds filled with spices and china and other luxuries, also crowded the skies.

This location is not accidental, nor is it without meaning. Amsterdam was at the time building itself into one of Europe’s great modern cities. Its canals are the most visible pieces of a vast machine specially-built to support the accumulation and circulation of goods and wealth. The congregation that built the Westerkerk helped build the modern global trade networks, modern finance, and a city beautifully designed to support international commerce: they could literally sail ships to the doorsteps of their houses, and unload their wares into storage facilities on the top floor (that’s why so many houses have hoists and winches on their roofs).

And they put the Westerkerk right in the middle of it. Made by rich by global trade and commerce, the church’s founders felt the need to declare that while they lived in a world that rewarded work, it was just as important to make time in their lives for prayer, thanks — and rest. In the middle of this whirlwind of commerce they located a sanctuary dedicated to worship and rest, a retreat from the world made possible by their worldly success. Work and rest both had a place in the city, and in their daily lives, and that they needed both in order to have a deep and meaningful life.

This architectural arrangement reflects a wisdom that was once widely shared. The week before my Westerkerk talk I was in London to promote my book, and during a break between interviews I took a walk to Covent Garden.

Visitors to Covent Garden tend to flock to the shops and restaurants in the Covent Garden Market and around the square, or scour the Jubilee Market in search of inexpensive souvenirs and antiques. It’s the kind of space that draws bargain-hunters, flaneurs, and tourists alike.

But across from the market sits Covent Garden St. Paul’s, a church designed by the great English architect Inigo Jones.

Again, commerce and worship, work and rest stand side by side, and switching from the one to the other is simply a matter of crossing the Garden’s stone square.

You’d never see such an arrangement today. (The churches nearest Google’s and Facebook’s headquarters are more than a mile away, for example.) This doesn’t just reflect a decline in the importance of religion in everyday life; it also reflects a belief that rest and contemplation don’t have a place in everyday life.

In our busy lives we don’t think much about rest, nor do we regard it as important or interesting. Rest is something we do if we have time, or if we’re not too busy. Rest is simple: it’s inactivity, or a negative space defined by the absence of work. And if we treat overwork as a virtue or sign of ambition, and sleep deprivation as a sign of commitment, we may even see rest as weakness.

But as I argue in Rest, and I’ll argue here on Thrive Global, we should not regard rest as work’s opposite.

In a good life, work and rest support, strengthen, and sustain each other. We should recognize that rest is skill that we can cultivate and improve. And we should value rest as a source of creativity and wisdom. Just as we are adapting contemplative practices and meditation to the 21st century, developing apps that remind us to be mindful and stay focused, and churches are experimenting with technologies that reinvent worship and restore a place for the divine in the lives of believers, so too should we take rest seriously, recognize its value, and reclaim it for ourselves.

Originally published at medium.com