This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go there.

My favorite game by some distance is soccer. The game has been in the news lately, most recently with the arrival of the US Women’s National Team—who have done so much to bring attention and energy to the sport of soccer—at the Tokyo Olympics. In the spirit of the moment, I wanted to start with a story about women’s soccer, one that illustrates a key feature of the dynamics that shape our world—and our health.

A key issue in the soccer world, which has belatedly risen to the fore in recent years, is the pay gap between women’s soccer and men’s soccer. One often hears, as justification for a status quo where women players make less than men, that the pay gap simply reflects the fact that women’s soccer has a consistently smaller audience than men’s soccer. While it is true that the audience for women’s soccer is smaller, this begs the questions: did this disparity simply “happen”? Or were there discrete events in the past, choices made, which, over time, led to the present outcome? The answers lie in the history of organized women’s soccer, which dates back to the 19th century.

In the 1890s, there were several women’s soccer clubs in England. In the early 1900s, some of their matches attracted thousands of spectators. This progression, building in parallel with men’s soccer, came to an abrupt halt in 1921, when the Football Association banned women’s soccer from the grounds of its clubs, out of a belief that the game was “unsuitable” for women. It was more than 45 years later, in 1969, when the Women’s Football Association was formed.

It is hard to think that this early disinvestment in women’s soccer did not play a critical role in shaping public attitudes towards the sport, and in limiting the game’s reach by limiting women players’ access to the resources male players had. It makes sense that men’s soccer would have a larger audience today, given that the sport had a decades-long head start on enjoying the resources and institutional backing of the FA. This advantage can, to a large extent, be traced back to that initial decision to bar women from the FA’s clubs, a choice which has had a ripple effect over time, informing a culture where men’s soccer remains (though one hopes not forever) the dominant draw. Within the larger network of social, economic, and political choices that shape the world of professional soccer, the FA’s 20th century response to women playing the game has become, in the 21st century, a factor in shaping the present within which fans and players now live.

This dynamic—in which a seemingly small decision ripples over time and within complex circumstances to shape a major outcome—is an example of the butterfly effect. The butterfly effect is a phenomenon whereby tiny events, happening within complex systems, can unfold into large-scale changes. The concept of the butterfly effect is credited to Edward Norton Lorenz, a mathematician and meteorologist, who referred, in the context of chaos theory (a branch of mathematics he helped pioneer), to how the flapping wings of a butterfly could create a breeze which, unfolding across time and space, could ultimately inform the creation of a tornado. (It is worth noting that the butterfly effect is also sometimes linked to Ray Bradbury’s short story, “A Sound of Thunder.”) Core to the theory is the idea that small, even infinitesimal, changes to complex, nonlinear systems can produce significant effects over time.

The butterfly effect reflects the dynamics of a systems approach to health, in which health outcomes unfolding in populations are seen less as products of a linear equation and more as what they are—emergent properties of complexity, nested in overlapping systems. Within these systems, small changes can lead, over time and as a consequence of complexity, to outcomes of profound significance. This has implications for how we think about health, and for how we implement solutions towards a healthier world. It also matters for how we think about the status quo. It challenges our assumptions that certain states of affairs have always been so, and are the natural conditions of our world rather than the products of countless discrete variables rippling through time and across systems to shape the present. When we can see this complexity, we can start to imagine how we can better engage with it, towards shaping new outcomes, and a new status quo, one which is more supportive of health.

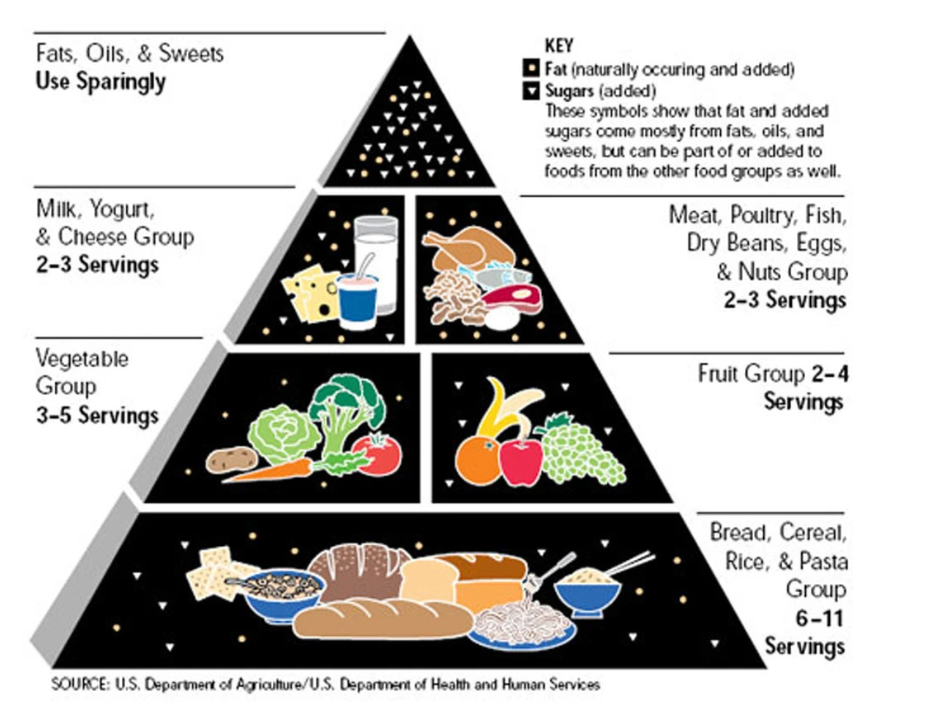

The following example is another reflection of the butterfly effect at work, this time explicitly in the context of health. Below is the USDA food pyramid that was in use between 1992 and 2005:

This food pyramid was long a key influence on how Americans eat, and was created to help them do so nutritiously. However, its broad warning against fat and seeming endorsement of carbohydrates elides many subtilties about the nutritional value of both. Not all fats are bad—indeed, some are necessary for health—and carbohydrates are not an unalloyed good, with some forms having done much to contribute to the obesity epidemic. The design of the food pyramid, then, reflects seemingly small choices which, over time, unfolded into something of great significance for health. But the nature of this significance was likely not what those who made the initial choices would have predicted.

The takeaways from the examples of women’s soccer and the food pyramid are, I think, threefold. The first takeaway is that decisions matter, and the seeming significance or insignificance of a decision in the moment it is made is not always a good predictor of its influence over time and across complex systems. The flapping of a butterfly’s wings on Monday could indeed help create a tornado on Thursday of next week, or it could amount to nothing. We cannot know and should therefore respect the possibility of either outcome.

This leads to the second takeaway, which is that, within the context of complex systems, it does not always matter whether choices are made with good or bad intentions. The history of women’s soccer is a case where a choice was made with intentions we now recognize as sexist. That such intentions led to a suboptimal outcome feels logical. But what about choices made with what seems like an eye towards health, and yet which still lead us astray? That is where the food pyramid example is instructive. The choice in 1992 to present a simplified version of the dietary significance of carbohydrates and fats was made with the best of intentions—to give Americans an easy-to-understand guide for healthy eating. Yet, over time, it has become possible to see how this choice may have contributed to a less-than-healthy present.

The third takeaway is that, given the power of these choices, it is clear that the status quo around health is, in fact, malleable, and shaped by the choices we make in the context of complexity. It did not have to be the case that women’s soccer has a smaller audience than men’s, just as it did not have to be the case that Americans eat more carbohydrates than they probably should. This pushes us to test our assumptions about why the world is the way it is, and about our power to make it otherwise. Our choices—all of them—have the capacity to shape health for better or for worse and we often do not know which effect they will have until long after we have made them. This should cause us to proceed with due humility, and with a willingness to think about how our choices may shape the status quo around health not just in the moment, but in the years to come, informing our sense of the tradeoffs involved in such decisions.

For example, consider the potential long-term effect of COVID school closures on the health and wellbeing of students in the years ahead. Education, particularly early education, is core to long-term health. The educational disruption caused by the pandemic has the potential to create consequences for population health which may not become apparent for quite a while, but which will likely be deeply significant to health when they do manifest themselves. We knew this to be a possibility when we chose to close schools, but the decision was made that the risk of COVID was greater than the long-term risk of educational disruption. Yet, as significant a decision as the choice to close schools was at the time it was made, it is hard not to think its significance may loom even larger in the coming years, as the butterfly effect manifests itself in the health of those most affected by our recent choices.

Given the power of these choices, it falls on us to make sure that our decision-making is informed by a respect for their consequences—both short- and long-term, positive and negative. This can help us to remember that no present “just happens”; even the smallest of choices has the potential to change the world in dramatic ways. This is cause for hope, I think, as we work towards a healthier world, reflecting the power we all have to shape health to the good, in each choice we make.