I cry easily, whoop at the end of dance performances and am passionate about my work. My partner would tell you it’s not possible to have a conversation with me that does not involve me sharing my feelings.

And I think the world would be a much better place if we raised men and boys to feel similarly empowered to experience and express sadness and fear, excitement and love.

But when I’m reading someone’s bio notes or cover letter to decide whether or not to hire them as my lawyer or webmaster or realtor, I’m more interested in their competency and experience than how they feel.

Emotional descriptors don’t convey competency

“Sally is passionate about …”, “Maria feels very strongly that…”, “Sabrina loves to write…” — these are not the best advertisements for your contributions.

I am passionate about sourdough bread but you wouldn’t hire me to bake you a loaf. I feel very strongly about a woman’s right to choose, but have no relevant employment skills for a women’s reproductive health clinic. I, too, love to write, but my emotional attachment to the activity isn’t what demonstrates that I do it well enough for you to pay me to do it for you.

Research into the language used in reference letters has documented the damage done to women’s career aspirations by champions who describe them in terms of their emotional affect or interpersonal style. It often undermines a candidate to emphasize her warmth, collegiality or energy, instead of the impact those qualities support her in having, such as achieving results, building effective teams, increasing productivity.

(To counter the phenomenon, the University of Arizona’s Commission on the Status of Women created a valuable one-page primer featuring research-backed advice for how not to inadvertently sabotage someone you’re supporting with gendered language.)

In addition to being conscious of how we characterize others, we also need to be mindful about how we’re feeding into or overcoming stereotypes when describing ourselves.

Take enthusiasm. It’s a wonderful quality, often contagious in a valuable way. But I recommend not leading with “I’m enthusiastic…” in your bio notes or cover letter, unless enthusiasm is central to your field, or the job you’re seeking. Are you applying to be a camp counsellor or motivational speaker? Go for it. Chief financial officer, deputy minister, surgeon? Better to emphasize the qualities and experiences that uniquely qualify you for success in those jobs.

Sharing passion without undermining credibility

Don’t get me wrong: This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be enthusiastic, passionate or bereft — particularly when you’re speaking in situations where part of your goal is to motivate others to care.

In a media interview skills workshop I led recently, several participants shared concerns about revealing their depth of passion for the issues on which their expertise is sought by journalists. Academics worry they’ll be seen as lacking in objectivity; they suspect that displaying emotional investment in their research will undermine its credibility, and — by extension — their own.

Meanwhile, violence against women advocates are wary about being dismissed as shrill or indefensibly alarmist. (Given that women’s lives are, literally at stake, this is an unreasonable burden to bear!)

But media interviews designed to help people understand an issue are different from academic journals, conference presentations or meetings with policy-makers. When you have an informed opinion about an issue, and you’re being interviewed by a journalist who’s looking for a way into the topic that will engage audiences, the emotional dimensions are not just relevant, they’re essential.

Because women have generally been given greater permission to remain in touch with and express our feelings, we have the opportunity to remind others of the emotional dimensions of an issue, which is more likely to drive home how people are affected and the consequences of failing to act.

Effective communicators of all genders recognize the value of complementing data with examples, illustrating history with personalities, enlivening concepts with evocative stories. And if, in the process of sharing those stories or the human implications of data, your emotional response becomes visible, that can be enormously powerful.

Dr. Henry: role model of effectively deployed emotion

In recent months, public health officers Theresa Tam, Deena Hinshaw and Bonnie Henry have become Canadian household names by virtue of their ability to clearly relay critically important information about the coronavirus and how we should be responding. Dr. Henry, in particular, has demonstrated her capacity to increase the relatability of data by accompanying it with emotional context.

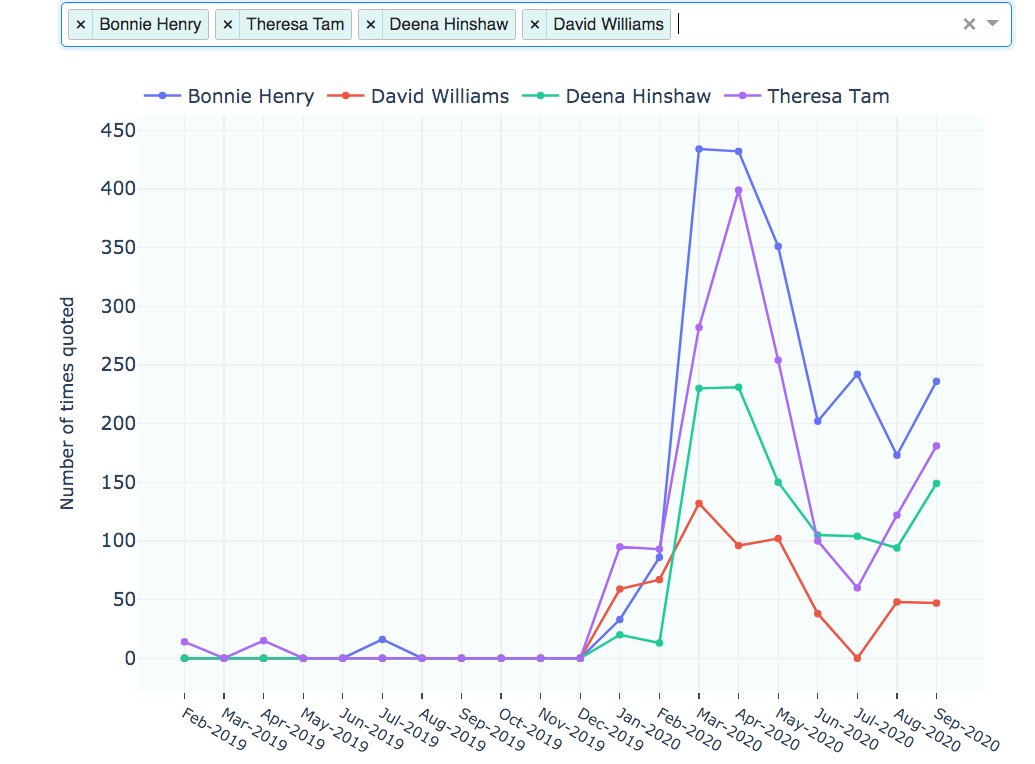

Fighting back tears at a news conference earlier this year, she confessed, “I’m feeling for the families and the people that are dealing with this right now.” Already recognized for her compassionate approach, her relatable display of vulnerability touched off an outpouring of support online. And it’s interesting to note how much more often Henry is quoted than her counterparts. This is partly a function of BC Premier John Horgan’s willingness to share the spotlight, but it’s also a testimony to the doctor’s effectiveness as a communicator.

“We know” or “It’s clear” vs “I feel”

But emotional admissions should be restricted to actual feelings, as opposed to being used as the lead into a sentence that deserves to be set up as factual information. Occasionally during a mock interview in one of our media skills workshops, an expert will start a sentence with “I feel” and risk undermining an audience’s perception of what follows.

Consider that “I feel women are suffering more from the pandemic than men” is not remotely as compelling as “We know…”, “It’s clear…” or “The research shows…” Someone with a different view can easily discount the “I feel” statement with the rejoinder, “Well, I feel that men are worse off.”

I am convinced (also a better alternative to “I feel”) that we can all benefit from paying attention to when and how our expressions of feeling are likely to reinforce vs undermine our comments.

Shari Graydon is the Catalyst of Informed Opinions, a non-profit working to amplify women’s voices and ensure they have as much influence in Canada’s public conversations as men’s.

We train smart women to speak up more often and more effectively.

We make them easier for journalists to find.

And your donation can help ensure that women’s perspectives are heard and exert influence in every arena that matters.