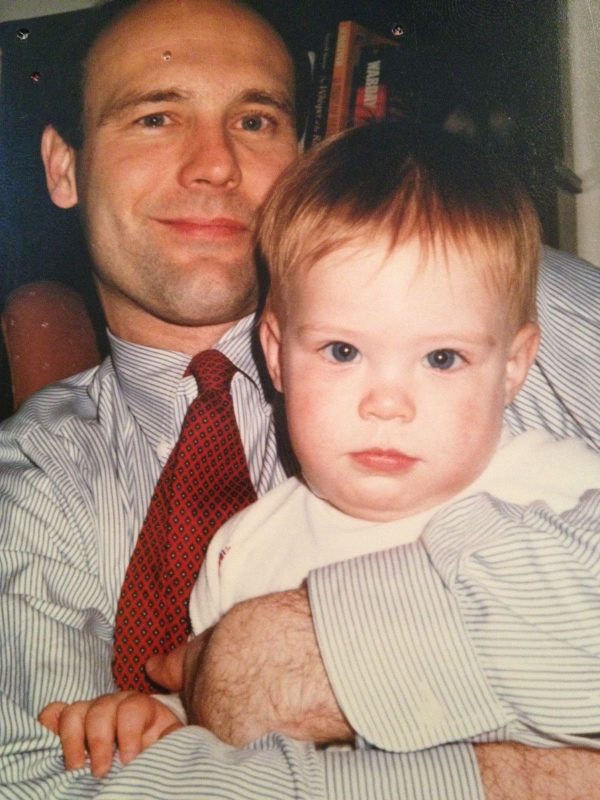

In his senior year of high school, John Cleveland had to write a 25-page paper about the events that shaped his life.

The theme, he knew right away, would be his dad’s job.

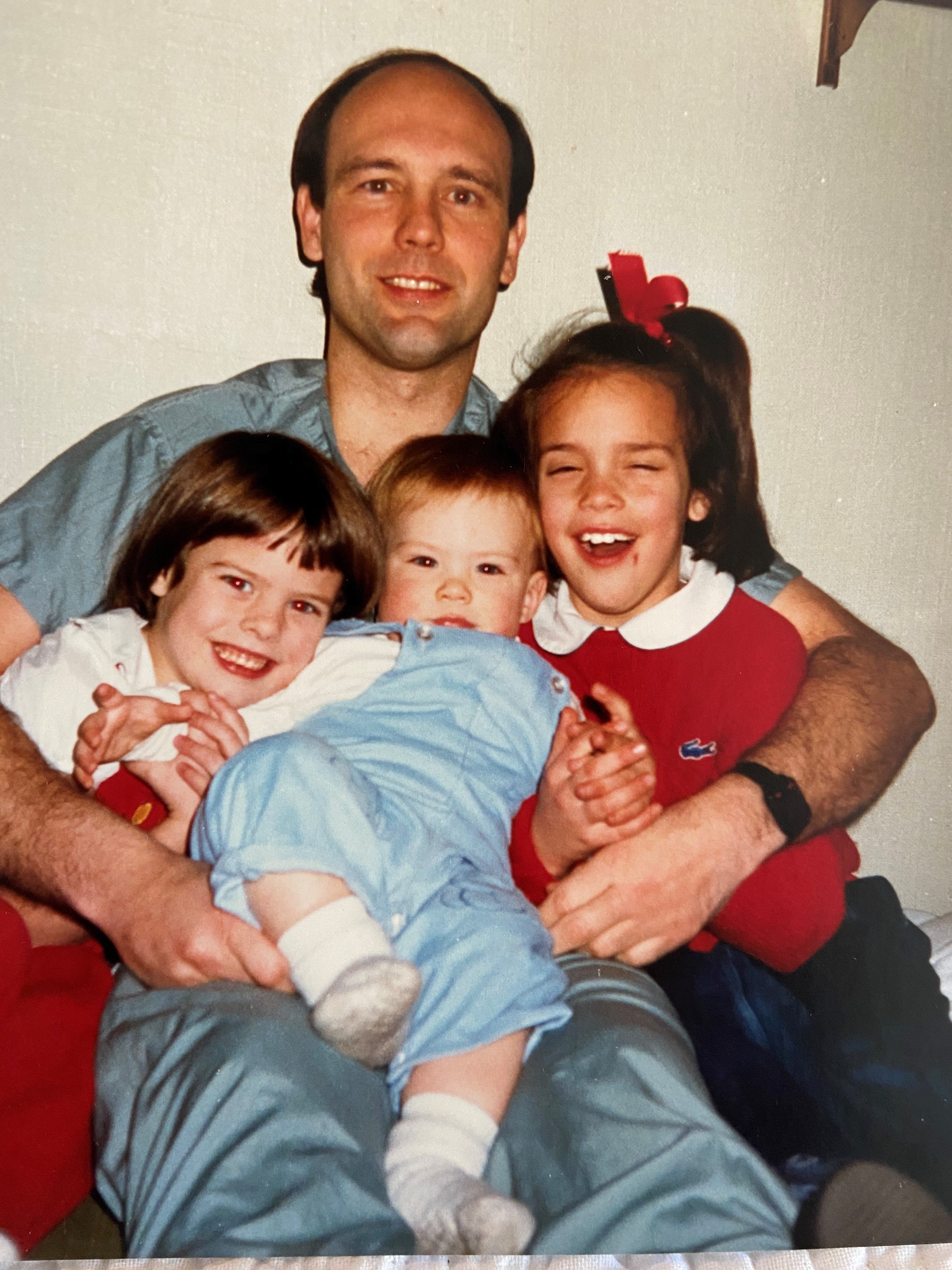

Because of it, John lived in five cities before landing in Phoenix only a few days before the start of high school. His two sisters were in college by then, leaving John feeling more alone than ever.

Work also often kept John’s dad from seeing John play piano, soccer and football. The night John scored two touchdowns, including the game-winner, “I walked off the field with only my mom.”

David Cleveland was a pediatric heart surgeon. John understood and appreciated that his dad saved sick babies. Many nights, John and his mom prayed for the patients. Still, the teen resented his dad spending time with other people’s kids instead of his own.

The easiest place for John to target his anger was the career.

“Despise is a strong word,” John said. “I learned to dislike his job. I did not want to be a heart surgeon, and I certainly didn’t want to be a congenital heart surgeon.”

This story is about how John changed his mind.

It’s about how John’s kids have lived in one city with their dad a vibrant part of their lives.

And it’s about John’s rebuilt relationship with his dad – a bond that’s grown so strong that they’re about to work together for the first time, and it’s on a project that could revolutionize the treatment of ailing hearts.

***

John left high school in a hurry to get on with his life.

He graduated from Auburn University in 2½ years and went to medical school at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He gravitated to surgery, specifically reconstructive plastic surgery. As an intern, he found himself treating a potentially once-in-a-career patient: a man mauled by a grizzly bear.

Hours into a complicated operation, John’s peers were still buzzing with excitement. He wasn’t.

“Something is incredibly wrong,” he thought.

John was weeks from starting a plastic surgery residency. Needing a new specialty, he scrambled into a rotation doing heart surgery. That led to participating in his first pediatric heart operation.

In the operating room, a veteran doctor threw question after question at the rookie. Even as the queries became more complex, John – who’d never studied this area, much less trained in it – aced the quiz. The look on the veteran doctor’s face sent John a clear message.

“This,” he thought, “feels like the right place to land.”

***

During John’s years in Phoenix, he and his dad played golf most weekends. David made a point of filling those hours with meaningful conversations.

What John had been too young to realize is how much it hurt David to miss so many of his children’s milestones. And it wasn’t until the 25-page paper that David realized how much it hurt John.

So when John was at Auburn, David visited often. They took trips together, just the two of them.

“We reconciled during that period,” John said.

By the time John landed in pediatric heart surgery, he understood the decisions his dad had to make. He also vowed to aim for jobs that would provide a more stable family life.

It wasn’t theoretical. Around the time John scrubbed in for his first pediatric heart surgery, he became a dad.

***

With a newborn at home, John began a fellowship at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

He worked directly for Dr. Vaughn Starnes, who is such a leader in the field that an operation is known as “Starnes’ Procedure.”

They hit it off right away. Starnes liked John’s Alabama roots; John liked how much Starnes resembled his dad – the same age, similar values.

Starnes’ presence indicates CHLA’s quality. The hospital’s location ensures a heavy caseload. A byproduct of that combination is a large, skilled staff.

As John’s career progressed – and as his family grew from one child to three – he gladly remained at CHLA. He’s now on a team with six partners.

“I feel like we’re all interchangeable because of how excellent everybody here is,” John said. “There’s a level of trust that allows you to walk away from the job and have more of a work-life balance.”

In fact, on the day we spoke, John was leaving the office in time for his oldest daughter’s softball season finale. Even if an emergency case came in, a colleague would’ve handled it.

David never had that luxury. At best, he had a single partner.

***

John and David talk at least three times a week. Their conversations go wherever John takes them.

Between November and January, they often discussed a particular patient – a baby named Alex whom one of John’s colleagues described as having “a wackadoodle circulation.”

Alex was born with nothing connecting his heart and lungs. This congenital heart defect is called total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR). It happens to about one of every 10,000 babies.

TAPVR patients are born with that “missing” connection; it’s just in the wrong place. In Alex’s case, his heart connected to his liver.

What makes Alex’s case truly unique is that he was born 14 weeks premature.

TAPVR is rarely found in babies born that early. Development that would’ve happened in the womb was occurring in the neonatal intensive care unit – for better and for worse.

He was about a week old when doctors diagnosed the problem. They transferred Alex to CHLA, where John and his colleagues handle about six cases each year.

Alex was too small for surgery. He needed time to grow. Yet time was running out because of another issue.

Alex’s body was getting life-sustaining oxygenated blood by accident. A blood vessel connecting his lungs to his circulating blood that was supposed to close shortly after birth was closing slowly – and was likely to seal before Alex would be ready for the TAPVR surgery.

Now what?

As John and his colleagues brainstormed, someone remembered a medical journal article about a similar case elsewhere in the world. That patient was kept alive by propping open the vessel with the type of stent used to open a clogged coronary artery. They couldn’t find any examples of it being tried in the U.S.; they’d likely be the first.

While one team of doctors inserted the stent, John and another team were on standby to perform a last-gasp procedure if needed. They weren’t. The stent kept Alex alive 10 more weeks. He still weighed less than 4 pounds when complications meant it was time for the TAPVR surgery.

When John removed Alex’s heart from his chest, “it was about the size of my thumbnail.” Still, John and team were able to put Alex together the correct way.

Alex soon turns 8 months old. John’s colleagues are writing a journal article about the case.

***

John recently performed another complicated case that prompted David to say, “That’s just amazing! Tell me how you did that.”

Imagine the dynamics of such a conversation – intricacies understood by only the most specialized of specialists sprinkled in among discussions about all the usual things fathers and sons discuss.

“There’s so much nuance to it,” John said. “I could go on talking for days about my relationship with my dad and how it impacts how I work and how I think about my job. But the most important thing to me is that we have a good relationship.”

And soon they’ll be spending a lot more time together.

***

David now works at UAB. A few years ago, he and his colleagues began studying pig hearts that had been genetically modified to trigger less of an immune response in humans.

Early research has sparked hope that the pig hearts could eventually be implanted in people waiting for a new human heart (what’s called “bridge to transplant”) or perhaps even instead of a human heart.

If they’re approved for human use, the first candidates will be children with a particular type of heart problem. CHLA happens to treat about as many of those patients as any facility in the world.

So when David was in Los Angeles for a conference in February 2020, he spoke about his project at CHLA.

Because of the pandemic, John and David haven’t been together since.

That changes this weekend. They’re meeting in Colorado for a Father’s Day reunion, a trip featuring just the two of them, like they used to do during John’s college days.

“We’re going to boat down a river, camp and try to catch some trout,” John said.

Later this summer, they’ll meet again. Professionally.

David’s research has advanced to the point where the genetically modified pig hearts will be implanted in baboons. The team will include John on behalf of CHLA.

Their collaboration will begin later this summer at a primate facility in Texas. How long it lasts depends on how successful they are.

John is cautiously optimistic, noting that cross-species heart transplants have long been considered the future of medicine and – the joke is – always will be.

Maybe the Drs. Cleveland will be the ones to break through.

The odds are long, of course. But there was once a time when John Cleveland becoming a pediatric heart surgeon was unimaginable, too.