This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go there.

Covid-19 has been, in many ways, a high watermark moment for public health. Over the last year, health authorities have engaged with the public, with the goal of influencing behavior in order to save lives. And the public has largely listened. Certainly, there have been loud voices protesting against public health’s advice. There have been many who have shunned mask-wearing and distancing, who even—to this day—downplay the severity of the virus. But there have also been many who have heeded the advice of public health, making drastic changes to their lives in the name of health.

A key reason, perhaps, that public health advice has so resonated is that it has tried to offer clarity in the midst of a disorienting moment. This clarity comes largely from our data. Throughout Covid-19, public health recommendations have largely been supported by our growing knowledge of the disease. For example, the data reliably show that the virus spreads through the air, via person-to-person contact. This allows us to clearly say that masks and physical distancing are an effective means of slowing the disease’s spread. This clarity has led to the widespread embrace of these measures, which, despite pockets of resistance in the US, have come to define our response to Covid-19.

Unfortunately, this resistance points to the limits of clarity. At the heart of the recalcitrance we have encountered is the politicization of many aspects of the pandemic over the last year. This politicization was characteristic of the Trump era, when partisan battle lines, which once chiefly reflected differences of opinion over policy, started to run through almost every aspect of our lives. This includes our attitudes towards the science of Covid-19, and—perhaps more to the point—our attitudes towards other people’s attitudes towards the science. As a consequence of this, much of the country, following the former President’s lead, has taken a dim view of public health’s advice, if not outright rejected it, while much of the rest of the country has vilified them for this.

This has only led public health to lean further into the business of telling people what to do. It has also, in my assessment, heightened a tendency among some to shame and condemn those who do not follow specific health advice. These tendencies have converged from time to time, which has only further politicized science and limited its scope, even at a moment of heightened influence for public health. For its part, public health has at times embraced this tendency to cast Covid-laxity as a moral failure, in the interest of encouraging wider compliance with pandemic protocols. The pictures below, for example, are from a UK government-run ad campaign. They reflect the use of blame in the name of health, essentially pointing a finger at the viewer, as if to say “Your moral failure is the cause of this sickness.”

Public health has long had an uneasy relationship with scapegoating and stigma. We generally oppose it, with the understanding that it informs the marginalization that creates health gaps and limits the scope of prevention efforts. Yet the truth is that we selectively embrace stigma, when we feel doing so will support health. The classic example is smoking. Smoking has declined over the last 50 years because of greater regulation of the tobacco industry, yes, but also because it has become socially unacceptable to smoke. That it is now regarded as such is due, in part, to public health’s willingness to make explicit the risks that smokers impose not just on themselves, but on communities. Put simply: We have embraced the stigmatization of a certain behavior in the name of the common good. Anti-smoking ads have reflected this; for example, looking at the ad below, it is not difficult to see where current, stigma-friendly Covid campaigns may have found inspiration.

Having said this, it is important to note the obvious: smoking kills, and we have spent the last 50 years making sure as many people as possible know it too. This knowledge is now so common that there is indeed a case to be made that anyone who smokes in 2021 willingly puts themselves at risk. We can now plausibly say the choice to smoke or not smoke is, in a sense, a choice between right and wrong. The same is to some extent true of Covid-19. We doknow that wearing masks and limiting our physical interaction will reduce the spread of the disease. Taking these steps is—there is no getting around it—a matter of personal responsibility, a moral consideration, and we ought to acknowledge this.

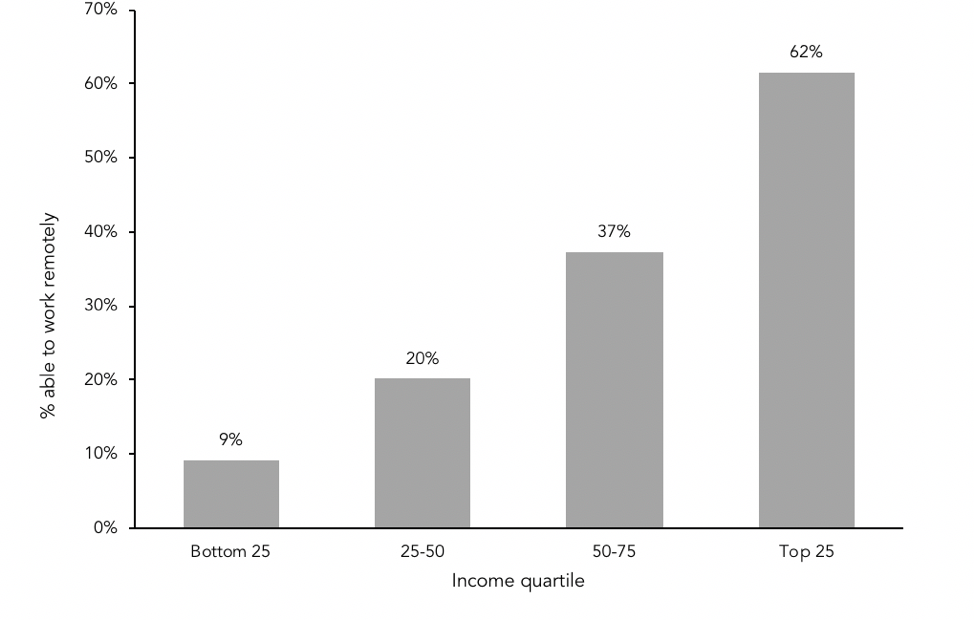

But there is also real peril in a public health approach that is steeped in moralism. Such an approach can overlook the conditions that constrain people’s lives and choices. Just as we should not ignore personal responsibility, we should not ignore how factors like employment, income, education level, and neighborhood context affect our ability to choose health in all our decisions. We know, for example, that there is a clear link between income quartile and our ability to physically distance by working remotely. The figure below, using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows how 62 percent of earners in the top 25th quartile were able to work remotely, compared to just nine percent of those in the bottom 25th. Messaging that shames people for not staying home may be pushing away the very populations we aim to protect.

The implication here is that, in stigmatizing those who do not adhere to physical distancing protocols, we risk targeting those with the least amount of personal control over whether or not they do so. We also know that stigmatizing behavior can be harmful in and of itself. In 2009, I worked with Jennifer Stuber and Bruce Link on a study of smoking and stigma. We found smoker-related stigma, however good the intentions behind it, can sometimes function as a negative influence on wellbeing, particularly when it encourages secrecy and social withdrawal due to a feeling of being devalued by society on account of their choices.

Then there is the important question of whether or not stigma actually works as a means of encouraging healthier behavior. I am not so sure that it does. The data on the efficacy of behavioral modification interventions are quite dubious. Indeed, there is evidence which suggests overly negative public health advertising can sometimes be lesseffective. At the very least, the task of getting public health messaging right is complex, and ill-served by one-size-fits-all approaches. People are complicated, and using shame as a cudgel in every case will not always have the desired effect.

It can even backfire. Let us take as a case study one of the most important efforts that public health is tackling right now: addressing deeply rooted systems of racial inequity and injustice. That structural racism is a real and present threat to the health of the public is inarguable. That we should be tackling this challenge head on equally so. But one approach that has been adopted in many workplaces, to the exclusion of real engagement with harder, deeper challenges, has been workplace diversity programs. These have proliferated in the past decade. Such programs have been widely embraced out of the best possible motives—to address bias, promote understanding across barriers of perceived difference, and create more inclusive work environments where everyone can thrive. Implicit in hosting these programs is the acknowledgement that bias is deeply undesirable, and that anyone supporting such bias is on the wrong side not just of company policy, but of morality. This raises the stakes considerably, as it should. Workplace bias, incidents of bigotry, and discriminatory systems have no place in a functional organization, or, indeed, in a healthy society. Yet data suggest that diversity programs are not always effective at changing behavior, and can, at times, actually reinforce bias. This can be a consequence of participants chafing at what they can see as a coercive element to the trainings.

To reiterate: such deeper engagement with racism, and its structural effects, is very much to the good, in fact critical to our mission. The work of public health is in large part the work of understanding how our country’s racial history has created systemic disadvantage for communities of color. At the same time, an approach to addressing systems that underlie racial injustice that leads with condemnation, that overlooks the individuals at the heart of systems, and that minimizes the critical role of mercy and forgiveness can risk undermining the broader goals of justice-oriented change movements. Moralism may indeed be useful in encouraging healthier behaviors, but only when coupled with true compassion and the understanding that we are not exempt from the standards to which we hold others. Moralism, to be effective, may need mercy in parallel. With this in mind, we should tread lightly, particularly when we are most tempted to take a harder line.

This is, I suggest, particularly important in our current moment, when virtue is often confused with virtue signaling, a confusion encouraged by the incentives of social media. Online, it is easy to criticize, to condemn, and to feel righteous for sounding “good” or virtuous. The question we must ask is: what is this actually accomplishing? Is it advancing the cause of a healthier world? Or are we merely spinning our wheels? Or, worse, are we actively setting our cause back by sowing the seeds of backlash rather than doing the harder, but arguably more effective work, of reaching out to others in full awareness of the complexity of their lives and motivations, and engaging from a place of humility and good faith?

It is necessary that we pose these questions, and answer them honestly, because it is necessary that public health be seen as credible, particularly in this time of crisis. If it is not, if people tune us out, or reflexively do the opposite of what we recommend simply because they do not like us, then it does not matter the knowledge we generate, how clever the solutions we propose, or how firmly on the right side of history we feel we are—we will fail in our efforts. We will be seen not as figures to be trusted, but as prim moralizers or tiresome pedants.

There is a stock character in commedia dell’arte, known as Il Dottore. He is a classic pedant, a parody of educated elites: well-read, decadent, verbose, stuffed with useless knowledge—useless because no one takes him seriously. We cannot afford to be him. When public health is dismissed, it is ineffectual, and when it is ineffectual, people sicken and die. Moralizing may make us feel right—it may even allow us to feel effective—but, in the end, it does no favors for health.