“I do this work in honour of my Mom, because my Mom’s life mattered” – Teoni Spathelfer

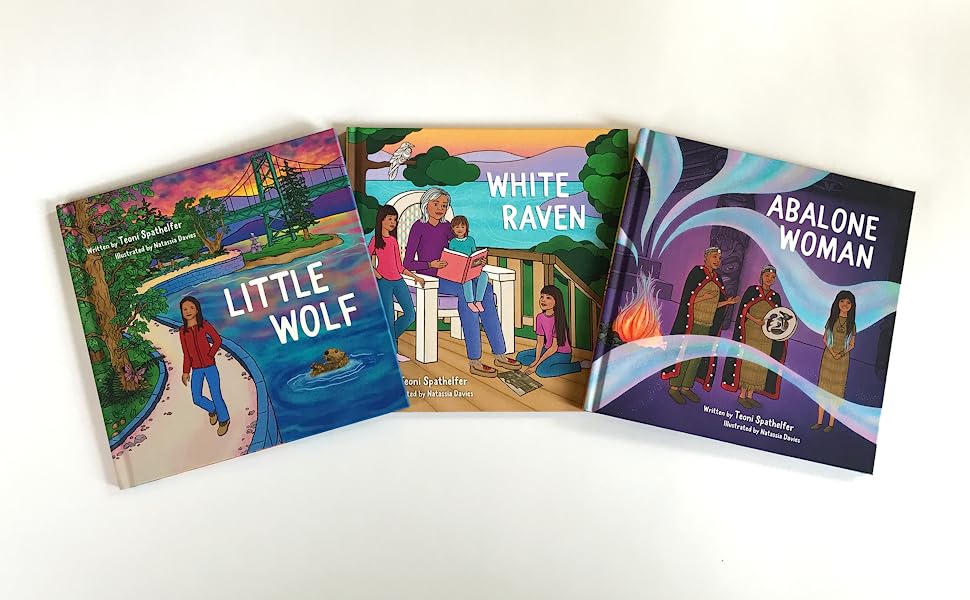

“Little Wolf” was the first book, part of a trilogy written by Heiltsuk Nation member Teoni Spathelfer. In “White Raven” Little Wolf is non longer a young girl struggling to adjust to her new life in the city, far away from the Nature she so deeply loved. As she learns to see the beauty in her new surroundings, Little Wolf, continues to cherish her traditional land and culture through beading and dance classes. Little Wolf does not waver despite the difficult start. She grows up proud of her Indigenous background and is ready to undertake the challenges and the adventures of life.

As a grown woman with a family of her own Little Wolf moves out of the city and into the country, to the island where she was born. The young family lives immersed in the traditions of the First Nation people. Orcas, sea lions, forests, woodpeckers, wildflowers and eagles become the connection between heart, mind and spirit. A “school” that cannot be matched by any human thought of institution. A school where truth and justice find their sole meaning and prepare Little Wolf’s young daughters to learn about a painful story. That of their beloved grandmother Lena, White Raven.

Imagine being born in a beautiful island village, surrounded by family, community and nature. Imagine a happy six year old girl, picture her in your mind. Imagine that little girl and other children suddenly being taken away from those their loved ones, from their parents, from their grandparents, from their uncles and aunts, from their friends, from home. Imagine these children, children, being put on a boat. Imagine them travelling for two days, imagine them being taken far away from their village to a place called St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. Let us reflect for a moment on the meaning of the word “school”. Imagine how terrified these children were when they arrived and saw so many strangers. White Raven was one of 150,000 Indigenous children from across Canada who were forced to attend residential schools. Imagine not being able to fall asleep because someone in the dormitory is always crying because they miss their mom and dad. Imagine White Raven’s hair being shaved off. Imagine someone applying DDT on her little head. Feel the skin burning. Imagine this being done to all the children in residential schools because the monsters who worked in these places thought all children had lice. Imagine never having enough food to eat, imagine the food often being rotten. Imagine feeling sick after having eaten raw sausages. Imagine only being able to eat fresh fruit at Christmas. Imagine eating toilet paper to make your hunger pains go away. Imagine not being allowed to see, play or talk to your little sister who is with you in the same residential school. Imagine having your mouth washed with soap if you dare to speak your native language. White Raven was not Lena, she was number 534. Imagine being called by that number to take a shower. Imagine the water being icy, freezing cold. Imagine a child not being able to see the blackboard because she needs glasses and the teacher making fun of that child infront of the whole class. Imagine a child going to school and having to pick up garbage in the fields, wash dishes in the kitchen and milk cows. Imagine children having to drink watered-down powdered milk while staff is allowed to drink the fresh cow’s milk. Imagine a child having to live like this for ten years, ten endless years. When Lena White Raven finally left the prison that the Government of Canada and religious institutions of the time had the audacity to call schools, she suffered post-traumatic stress disorder for most of her adult life.

Can we imagine? How could we ever imagine?

Although Lena managed to feel some solace in finding the courage to come out and speak of the atrocities she endured for so many years, she did not manage to see the day the Canadian government announced that all Residential School Survivors would be compensated for each year they spent in those prisons. The decision came too late for Lena who also deserved compensation. Sadly, she passed away six months prior to the news.

My dear grandchildren. Remember that you can do anything in life if you focus on it. I will always be proud of you, no matter what. Always know that the things that make you different are the things that make you beautiful and strong!

Lena White Raven

Teoni does presentations and readings in schools about her Mom’s residential school experience and about the history of the schools in Canada. She talks about Reconciliation as a way for First Nations and all communities to move forward together into a future where this history is understood and all cultures are appreciated.

Giaxsixa my beautiful friend Teoni. My heart is with you always. Christina.