During this Covid-19 winter, my neighborhood sprouted homeless encampments under the scaffolding around commercial buildings whose renovations and offices were abandoned during the New York State mandatory lockdown. We have always had homeless men and women living on the streets here. We knew them and they knew us. I helped some and learned their stories. However, these new residents were younger, more aggressive, and clearly more desperate. My Citizen app lit up with reports of knife fights, assaults, robberies, and purse snatchings. I didn’t like it; I was feeling afraid.

Of course, the real danger was not these homeless men, but the novel Corona virus. I could see these unruly men, living inconveniently in my neighborhood; I could not see the virus.

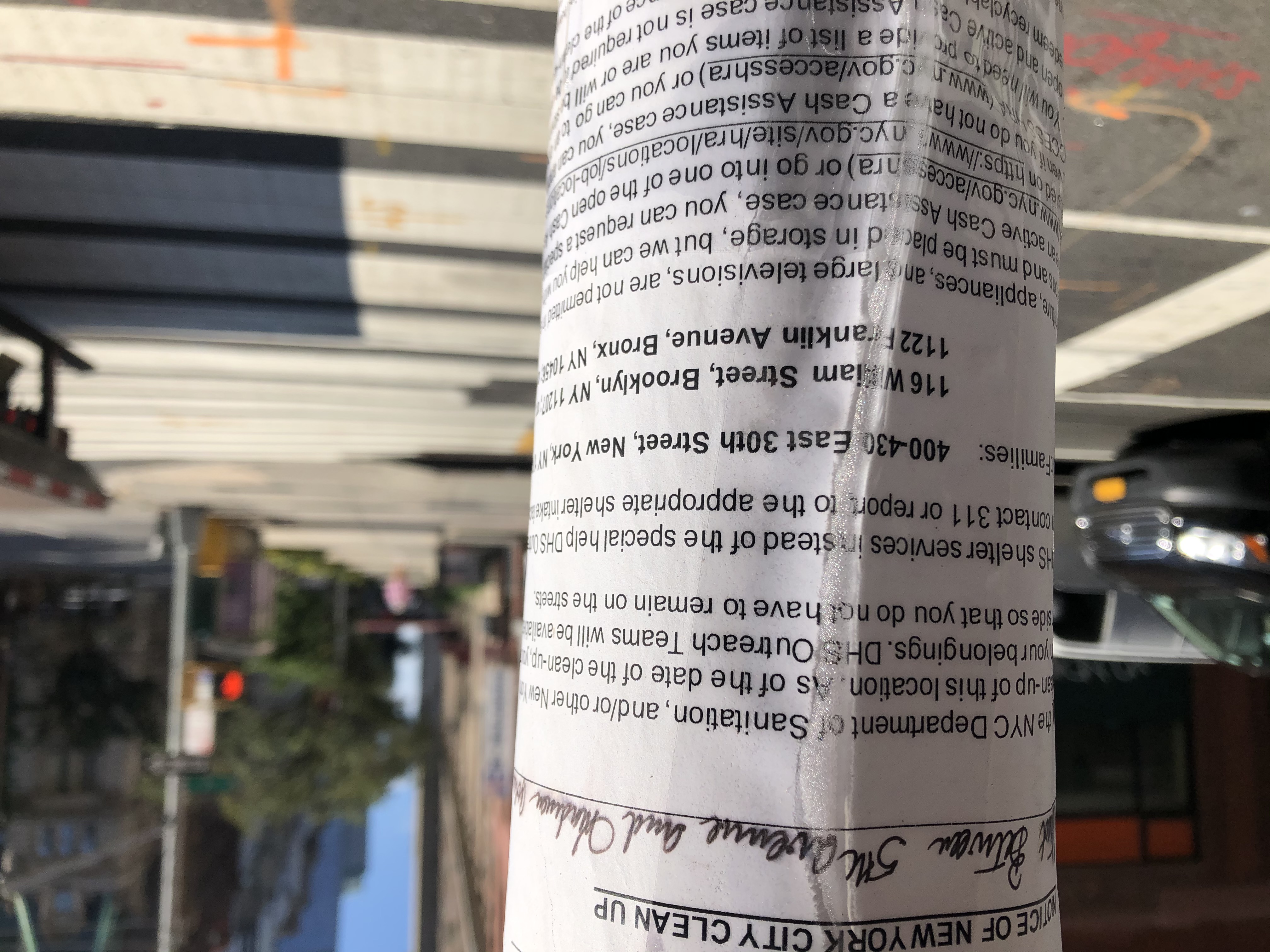

I admit to feeling relief when I saw the notices taped to utility poles on the side streets: these homeless households would be cleared away by the Department of Sanitation no later than August 18th, social service workers would assist residents to find temporary housing, and cash payments would be awarded to help relocate folks.

It’s lazy to just be afraid. Fear isolates us and inhibits our ability to feel compassion and empathy for those who suffer. To combat my fear, I had befriended one man who regularly panhandles on 36th Street. He is bearded and bowl-legged. He did not serve in the Armed Forces, as many other homeless men in the neighborhood had. Occasionally he had a black eye or a bandaged hand. Life on the streets of New York City must be unbearably tough. I started by giving him money mostly from my quarter collection, which I would leave at a hollowed out telephone booth to avoid getting closer than six feet since he doesn’t wear a mask. Then as the neighborhood filled with more homeless men, I increased my donation so that he could at least buy a daily meal. He was always polite and thanked me. We greeted each other even when I had already given him money for the day. Once he offered to carry my bags filled with fresh vegetables from the farmers market.

Two weeks ago he disappeared, even before the notices went up and the ominous August 18th deadline loomed. I wanted to feel relieved that perhaps he had found a permanent home, instead I found myself worrying about him. Had he been arrested? Was he even still alive?

This week he was back. He had lost his housing. I didn’t ask why; it isn’t my business. But from the look in his eyes, I know he occasionally uses heroin and often drinks too much. And I know he gets into fights. I assumed he broke some rule involving drugs or alcohol, or being uncooperative. Here he was coming back to his home on our corner.

There are 200,000 pending eviction cases filed before March 17, 2020, the date of the New York lockdown and the start of a moratorium on residential evictions. 200,000 is an enormous number, almost too big to contemplate, and that number doesn’t include all of the tenants who have gone into default since March 17th. There remains a moratorium on new evictions until at least October 1st.

Where will these men, women, and children go? These are not hardened homeless people like the bearded man on my corner, but grandmothers, aunts, uncles, single mothers, recovering Covid-19 patients, essential workers who might have lost their jobs because they got sick or had to care for a loved one. And these people include children and multiple generations of extended families. What cruelty will allow these individuals and their families to be removed from their homes and placed on the streets in the middle of a pandemic and economic crisis?

We have choices now. We can get paralyzed with fear and insist that the dispossessed disappear from our daily lives. We can blame the victims of a pandemic, the unemployed, the ill and disabled, as well people of color whose economic stability and emotional wellbeing is kept tenuous by discrimination and structural racism. We can live in a society that fears these fellow human beings because they are damning evidence of a failing economic and political system.

Or we can face our history and acknowledge that greed, racism, and entitlement are overshadowing the principles of our better selves–community, equality, fairness. We can instead nurture these men, women, and children and treat them as individuals deserving of our compassion and respect. These are real choices and are being presented to us on the November 3rd ballot. Which kind of society do I want to live in?