Nothing is particularly hard if you divide it into small jobs. — Henry Ford

Ideas have an annoying habit of not showing up as doable projects. They show up either as loose goals (as opposed to SMART goals) or, even worse, as “wouldn’t it be cool/nice/fun if …” nudges that immediately take up residence in that crowded part of our brain and leech small amounts of cognitive energy until they all revolt. (Or maybe that’s just me.)

Being able to think of the next action is a great way to make your ideas actionable, but when you get serious about moving on that project, you’ll have to start thinking in terms of chunks. Keep in mind that doing a next-action exercise won’t necessarily be a fruitful way to chunk a project down because you might get a long list of actions that are too granular for you to see the shape of the project; it’s easy to start listing leaves (actions), when you’d be better off looking at the trees (chunk) in the forest (idea).

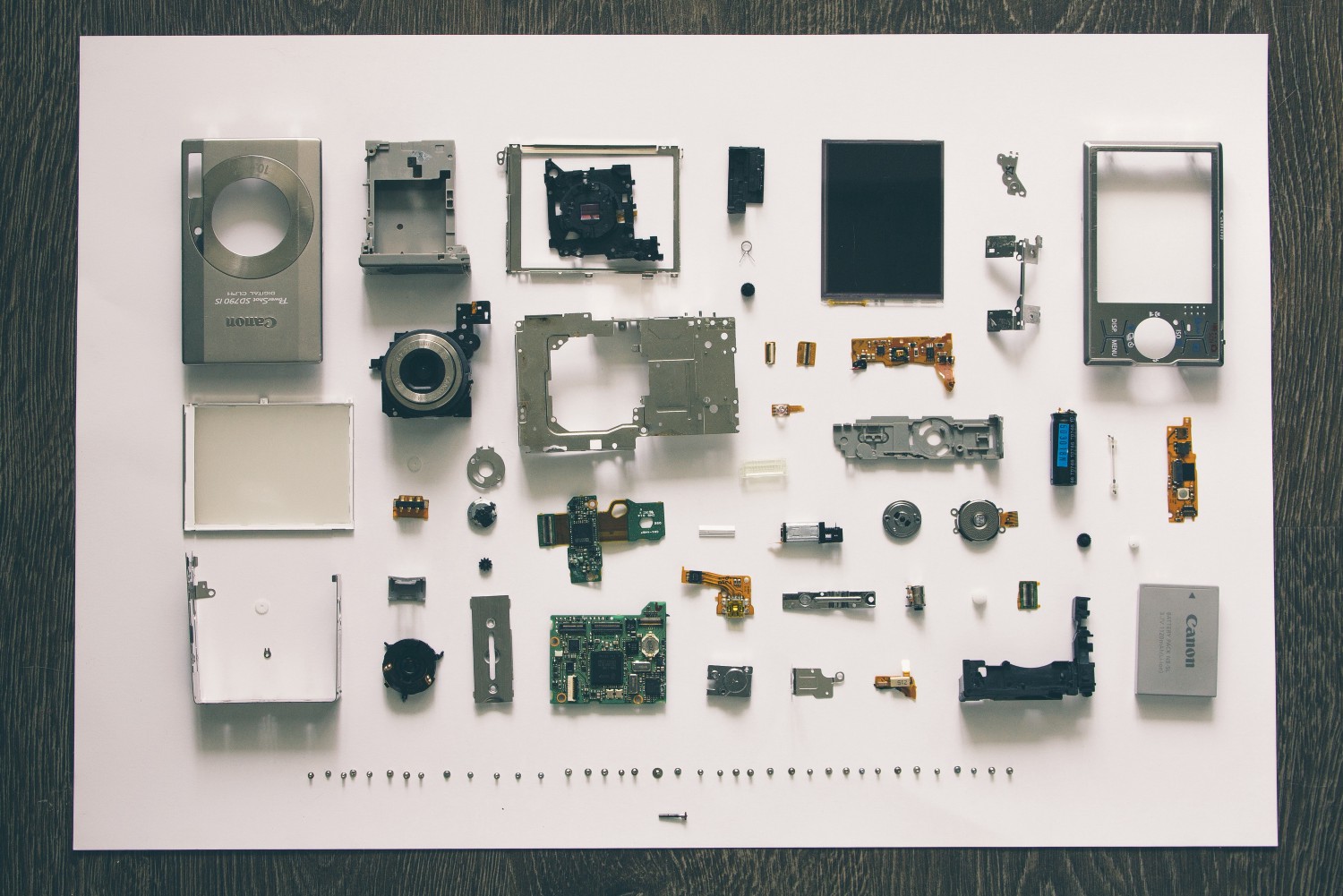

Chunking your projects down into manageable parts is a critical step in moving from idea to done.

There’s a bit of an art to chunking projects down, mostly because you have to keep two variables in mind:

- What are the discrete elements of the project?

- How much detail do you need to include to drive action for the project?

A few examples may help here, so I’ll discuss a creative project, a business project, and a personal project.

Let’s start with a book since it’s familiar to most of us. A book can be divided into chapters, and chapters can be divided into sections. Sections may have sub-sections, fiction writers might call sections “scenes,” and we might quibble over whether a glossary is a chapter, but the point isn’t about what we call the chunks; the point is that the chunks are pretty straightforward here. You don’t write books; you write sections by writing a discrete number of paragraphs at a time. A chunked book-writing project plan might look like this:

- Make an outline of topics or scenes, chunking down to sections as much as you can.

- Determine whether you’ll have your finished product professionally edited. (I’ll assume yes because you’re a great writer.)

- Get a list of potential editors.

- Contact editors to determine availability and fit.

- Select your editor.

- Draft individual sections (rinse and repeat).

- Edit drafts en masse so you can see the structure and common themes.

- Rewrite sections as needed.

- Send your manuscript to your editor.

- Figure out what you’ll do besides pacing while waiting for your editor to get back to you (may I suggest yoga or exercising?).

- Review your editor’s comments (which means being simultaneously excited about and exasperated with the commentary you received).

- Rewrite the book sections to address the commentary from your editor.

- Send the revised manuscript back to your editor (and thus, do more pacing, exercising, or crocheting while you wait again).

- Address final editorial concerns in the manuscript.

Let’s now consider a business project, say, hiring a new teammate. For that project, you’ll need to:

- Determine what you need the teammate to do.

- Draft or modify a job description.

- Post that job description.

- Review applicants.

- Cull applicants.

- Interview applicants.

- Select the 1–3 candidates you want to hire.

- Propose an offer to your top candidate.

- Propose an offer to your second candidate because your top candidate inevitably will have been hired or moved on to something different.

- Negotiate with that candidate.

- Confirm the final agreement with the candidate.

The individual components of the project might have varying degrees of difficulty, but it’s not hard to see what needs to be done.

One last project, on the personal side: putting garden beds in your yard. Here’s what that might look like:

- Determine what you’ll be planting in the garden beds, so you can determine how big they need to be and where they need to be.

- Select the location of the garden beds.

- Mark the locations where you’ll put the garden beds so you don’t forget.

- Determine whether you’re going to buy beds, have someone make them for you, or make them yourself. (I’ll go with the “make them yourself” option so that we don’t have to have a nested if-then list.)

- Research bed plan blueprints (or make your own if you’re wired that way).

- Make a list of materials and tools needed to make the bed.

- Cross-check your current materials and tools to make sure you don’t get something you already have (to avoid adding to the countless boxes of screws you’ve accrued over the years because you forget that you already have enough screws or can’t remember which screws you have — not that I know anything about that from personal experience).

- Set up your bed-building area, close to the place where you’ll actually put the beds (so you can put the tools and materials there and not have to move stuff around multiple times).

- Get the materials and tools you need to build the beds.

- Build the beds.

- Put the beds in the ground.

- Put the dirt in the beds.

- Prepare your “I made the garden beds” conversation hooks to use for bragging, negotiating, reminding, and celebrating as needed.

In each case, I hope you see that each chunk is a coherent, discrete piece with a clear start and finish. There are no mysteries about what need to be done.

You might notice that I put some non-obvious chunks earlier in the projects than you may have. For instance, on the book project, I put contacting an editor before writing your first draft. Why? Because it’s helpful to know who your editor is before you start writing so you can get some editorial support as you’re writing and because it addresses one of the drag points that happen in the writing process. Likewise, “set up your bed-building area” reduces the frustration of moving things multiple times just because you didn’t think the project through.

Tips to Make Chunking Your Projects Easier

Here are a few other tips that’ll help you chunk your projects:

- At this stage in the game, try to think just about the WHAT aspects of the project, not about WHEN you’ll do it. Put the pieces of the puzzle on the table before you start trying to put them together in the right way. (You’ll notice that I put things in order above, mostly because I can’t not do it.)

- Start each chunk with a verb. It’ll help you remember what actions need to be taken to move the project forward. (This is one of 7 Ways to Write Better Action Items.)

- Use the Two-Hour Rule as a guideline for your chunks. A natural question people have about chunking is how much to chunk projects down. The Two-Hour Rule comes in handy here, for the simple reason that we generally know how much we can get done in two focused hours and it allows us to start creating standard units of creative time for projects.

Take a look at your action lists for the week. What ideas or projects would benefit from being chunked down into two-hour blocks? Where will you find or make those two hours to work on that chunk of the project?

Charlie Gilkey is an author, business advisor, and podcaster who teaches people how to start finishing what matters most. Click here to get more tools that’ll help you be a productive, flourishing co-creator of a better tomorrow.

Originally published at journal.thriveglobal.com