The other day, one of my friends made an offhand comment that really grabbed my attention. She’d been having conflict after conflict with her preteen daughter, and she was feeling angry, frustrated, and emotionally exhausted. “I know it’s not just her, and it’s not just her age,” she said. “I can think of plenty of things I’ve said to her in the past that I wish I could take back. Sometimes I feel like I just want to give up!” Then, she laughed and rolled her eyes to let me know she wasn’t serious. But it got me thinking.

Like most parents, every day we discover (again) that we can’t come close to parenting perfectly. It can be painful when things don’t go well, as it is when we belatedly realize that we missed a golden opportunity that our kids were giving us to connect with them about something they care about, or we raised voices and tension interrupted what was meant to be a restful vacation day. Still, at some point we accept that parenting is a complicated life arena that simply can’t go well all of the time, or even most of the time.

We are parents for life—we can’t just toss in the towel and quit—and we bring the same type of understanding to our careers, our education, and other important life areas. We stay the course, take the challenges as they come, learn what works and what doesn’t, and move forward. We understand that life’s not perfect.

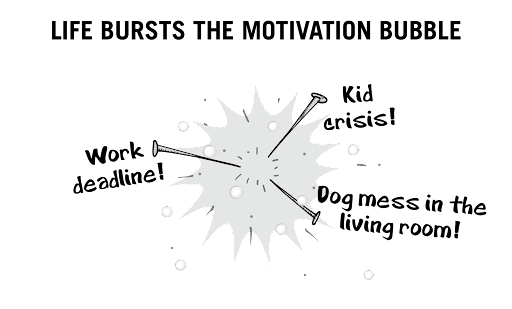

In my coaching around creating lasting changes in healthy behaviors, however, I rarely see people bring this same approach to eating and exercise. Instead, we create an idealized goal that aims for an idealized self, especially intertwined with weight pressures and beauty norms and self-worth. We stuff all of this into a motivation bubble so overinflated it can’t help but burst upon the tiniest impact with life. We see ourselves as less than perfect in relation to these perfect goals, and as more deserving of our blame when we can’t achieve that perfection we’re aiming for.

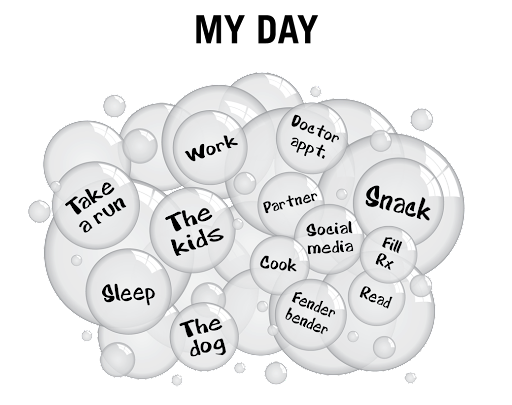

But the truth is, we are complex beings living in a complex world. Healthy eating and physical movement are just two elements of the whole of our lives. Think about it—are you primarily a person trying to eat according to a plan or work exercise into your daily routine, or is there more to you than that? The many moving parts in my own life that compete with my own efforts to eat well and stay active include work (and its subparts: researching, speaking, coaching, writing, and consulting), friending, parenting, partnering, daughtering, sistering, grocery shopping, cooking, list making, appointment keeping, dog walking . . . And on any given day, I need to value some of these more highly than others. An important call from my mom may cut into time allotted for research or I may need to take the dog to the vet when I had planned a walk.

It just depends, right? Life’s not perfect. We all know this about our lives, and we move our priorities around without much trouble, while simultaneously stumbling over our artificially inflated eating and exercise bubble. When a point of conflict arises—when our eating plan is challenged by a tempting dish or our bike ride is challenged by a sudden storm—it can feel like a crisis. We could follow the same imperfect path we take with conflicts to our work or family plans by doing a part of our eating or exercise plan, or we could just give up and try again next year. Typically, when facing these ominous conflicts to our ideal eating or exercise plan, we feel overwhelmed and it’s all too easy to give up. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

FOREVER BLOWING BUBBLES

Just for now, think of all the bits and pieces of your life as bubbles. We’ve got a lot of separate bubbles moving around in our daily lives. Work, family, health, finances, and housing are the big ones, the ones we naturally prioritize. Some are larger, some are smaller. Some rise to the top, some fall to the bottom or cling to the sides. They bump up against one another all the time. Sometimes when they collide, they burst on impact.

When we embark on a new eating strategy or exercise regimen, to finally be all that we can be, our eating or exercise plan bubble tends to get overinflated, obscuring all of our other life bubbles. Perhaps because it is idealized and it contains our perfect goal, we believe it will never burst. But then life happens. Our eating and exercise bubble bumps up against a higher-priority bubble like work or family and bursts on impact, sending all our plans (and aspirations) right down the drain.

As physiological beings, we have a real need to care for our bodies. Just to stay alive, we need to get enough food, water, and sleep, and to some degree move our bodies. But to do more than just survive, we also need to live our lives, fulfilling meaningful life roles—as employees, students, entrepreneurs, clinicians, professionals, creators, coaches, friends, parents, partners, caregivers. At any given time, a different bit of our life suddenly rises to the top of the priority list, needing our attention and our care and, in the process, often creating a very real conflict with our eating or exercise plan.

This point of conflict becomes our choice point: the true place of power. What we do here determines not only the fate of our specific eating and exercise plans, but our success in supporting the greater goals they aim to achieve. What I call “the Joy Choice” is the perfect imperfect option that lets us do something instead of nothing.

This decision strategy is based on the assumption that many of the plans we make do not work out, and it is all about learning to effortlessly and joyfully negotiate all of these choice points. A big part of that approach is having flexible beliefs and strategies that work for rather than against you and all the meaningful things that make up your life.

Flexibility doesn’t just sound good. It is considered the cognitive style needed for societies to flourish and is a prerequisite for successful innovation across life areas within our modern world. Flexible thinking is associated with a better quality of life and well-being, and is considered to be a fundamental aspect of health. It cultivates psychological resilience to negative life events, including better coping and emotion regulation within work, relationships, and leisure.

I’m banging the flexibility drum so loudly for a good reason. We’ve been told over and over again, across decades, to stick to the plan no matter what. This idea is so deeply embedded in our psyches that inevitably these inflexible plans get blown to smithereens, leaving us picking up the pieces, once again despondent and pessimistic about ever becoming successful.

But flexible thinking is our true superpower when it comes to successfully navigating choice points and making consistent decisions. This is especially true for caregivers and others living with many competing responsibilities.

Flexible thinking drives creativity and resilience in the face of challenges and unexpected sudden change. Studies generally find that when it comes to eating and exercise, being overly restrictive often backfires. However, flexible thinking enables us to better manage our food consumption and physical activity.

In fact, striving toward any plan or goal in a flexible way is considered paramount to continued engagement and long-term behavioral pursuit,not only in lifestyle behaviors but across many parts of life.

So, how ‘bout it? Are you ready to free yourself from what hasn’t worked (too many times to count) and join the growing number of people who have decided to align their new healthier eating and exercise practices with the perfectly imperfect ways that they flexibly, and successfully, manage their other life arenas?

The Joy Choice is yours.