Contradictions abound in the study of effective leadership.

For instance, we often expect our leaders to hold steady a consistent and unwavering vision of what they want for their organization. But we know that effective leaders must also be responsive to changes in their system and to the needs of their followers. Can both be true?

The surprising answer is that effective leaders must — and can — do both.

Create a Clear and Consistent Vision

A clear and consistent vision is a powerful motivator to enlist action amongst followers. But it can’t really be rigidly unwavering — the leader must also redefine the vision if it becomes obsolete or if — particularly in politics — a challenger comes along with a more compelling vision of what they offer. So a certain amount of revising the vision is healthy.

Know When to Change the Vision

This allowance for flexibility on vision does not mean that leaders should give in to the temptation to make deals with the devil to live and fight another day. When leaders become fearful of losing their influence, they often compromise their original vision and resort to less-principled transactions as a means of preserving their power and ability to influence change. The feeling of power and influence that comes with positional authority can be intoxicating and a distraction to the original vision.

More often than not, the articulation of a strong vision gets neglected because the reality of change gets in the way. So good leaders calibrate these competing needs, and understand when to maintain their vision and when to demonstrate flexibility. In the end, the best vision not only serves as a clear “north star” or “guide post,” but also gives a sense of stretch and new possibility, while also remaining feasible.

Calibrate the Ambition of the Vision

Leaders can exploit our tendency to want a better future by over-promising with their sense of vision. Eventually, this trap catches up with the leader, who inevitably ends up under-delivering and unintentionally becoming duplicitous. To prevent cynicism, good leaders manage the tension between between what is promised and what can be delivered, and keep the gap between the two from becoming too wide.

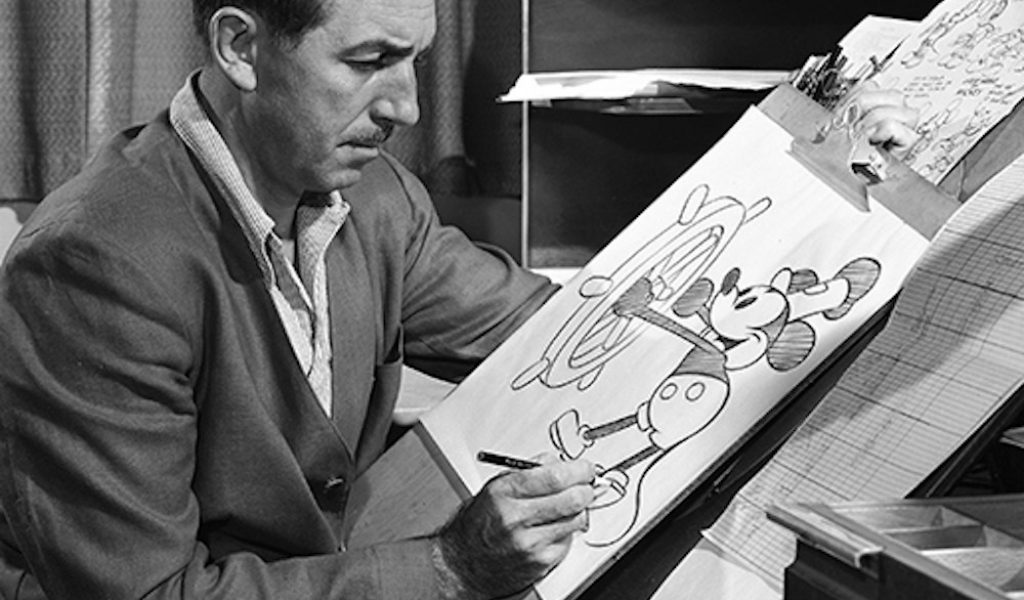

In our recent book, Leaders: Myth and Reality, we explore the case of Walt Disney, who was known for his extraordinary precedent-breaking vision, and also had an incredible record of making much of that vision a reality. But his success was not simply the product of vision — equally, it was achieved through persistence and many small but incremental steps, each of which was both a stretch and also feasible at the same time.

All of this means that followers must hold leaders accountable to the vision.

If a leader is slow to adjust when the vision becomes stale, the followers should make that known. If a leader loses sight of the original vision for the wrong reasons, as they are prone to do, it is incumbent upon the followers to remind the leader, and all of us, why we’ve invested in leadership in the first instance. Finally, the leader shouldn’t over-promise, but they inspire and motivate with a clear and positive sense of new possibility.

This piece was adapted from the answer to “We have often observed that many of the leaders lose sight of the vision they set out to achieve, they stumble and become a completely new version of themselves. Why is that?” that was asked during a recent Quora Session I hosted along with my co-authors, Jeff Eggers and Jason Mangone.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.