I remember looking over my left shoulder out of the large rear window of the limousine. My breath caught in my throat. I hadn’t expected to see so many cars. Slowly, respectfully, they snaked around the curve at the end of the long somber street. Headlights on.

I didn’t know there were so many people who cared. How did I not know that?

If only he had known how much he was loved. Perhaps he did know. Perhaps it just wasn’t enough.

I don’t remember much about those few days. It was as if I were living someone else’s life. In someone else’s body. Even as I look back now, there are distinct and specific moments I remember. And they follow a continuum. But it’s the stuff in between that’s gone.

In the early morning hours on Monday, July 25, 1988, I received a frantic call from my sister Kathleen. The ring jolted me out of a deep sleep. She was in London, Ontario, still living in the house that our mother owned. She shared the house with David.

Our mother, who at that time was spending the majority of the year on a little Caribbean island named Montserrat, had called Kathleen a few minutes prior. She was trying to reach David.

Apparently, Mom called him the night before but couldn’t get through. So she thought she’d just try again that morning.

Kathleen went to rouse David so that he could take the call. After knocking on his bedroom door a few times with no answer, she let herself in.

There he was. Lying face up on his bed. Naked. Eyes open. Blood coming out of his mouth.

She rushed back to the phone to let our mother know what she found, and was immediately told to call me. When I listened to Kathleen’s voice, I thought there must have been some mistake. That somehow she just saw something else. I told her to go to the neighbor’s house, and I hung up the phone.

A few minutes later, the phone rang again. She whispered, “He’s dead.” And I screamed.

Vaughn, a new tenant who was staying in the bedroom beside mine (I was living in my brother Denis’s house in Toronto), came rushing into my room. I don’t remember what I said to him. I don’t remember anything I said or did.

Shortly thereafter, Bruce K., a longtime friend of Denis’s (and a friend of my family’s), rang the doorbell. I opened the door to see his face heavy with grief, shock, and sadness. Unforgettable.

It must have been a couple of hours later when I was in my car, driving along the QEW highway, en route to London. I was frozen in shock. “Don’t Give Up” started playing on the radio. And it was while I was listening to Kate Bush’s ethereal, haunting voice that it hit me. When the reality of the situation could not be denied.

When I knew I would never see him again.

My dear, beautiful, sweet, sensitive, funny, intelligent, little brother David.

I don’t remember anything that was said that day when I arrived in London. Surely phone calls were made. Arrangements were handled. But for the life of me, I can’t remember a damn thing.

The only clear image I have is of my mother walking through the front door that night after her long and heartbroken journey home. I had never before seen her face look the way it did that night. I don’t have the words to describe it. There was insurmountable sorrow emanating from her body. It halted her gait and weighed her down to such an extent that I thought she would never be able to lift her head again. I felt as though I not only lost my little brother, but that my mother was gone as well.

No memory of what was said or done. Until Thursday morning.

The limousine continued its crawl. We were almost at our destination. The Forest Lawn Cemetery was just another mile or so ahead.

I returned my gaze to the front of the procession. My eyes locked on the car that held the hearse where my little brother lay silent and dreamless.

As the wrought iron archway of the cemetery entrance passed above, I prayed that David’s spirit was at peace. I hoped that somehow, somewhere he knew that he was loved.

September 2004

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline receives approximately two million calls a year. Two million. And those are the people who choose to reach out for help.

How many countless others suffer in silence?

Why has suicide become such a pandemic in our society?

I hate to say this—I feel ashamed in doing so—but I am growing numb to the news of another life being tragically taken by someone’s own hands. There are times when I must choose to numb my feelings, otherwise it’s just too heartbreaking.

I cannot help but ask myself, sometimes out loud: What the f*ck is going on?

Is it the crumbling of the family unit? How much does that play a part in the disappearance of hope for a fulfilling future?

Is it the secrecy, shame, and stigma that still exist about mental health issues, even though much progress has been made?

Is it because it’s too damn easy to label someone as having mental health issues, when all it really is, is loneliness, and isolation, and fear of intimacy?

Is it just being f*cked over too many times and giving up hope on humankind? Believing that no one is trustworthy?

Is it the lack of community that too many of us experience?

Is it our stupid smart phones and social media that oftentimes make us feel both connected and brutally disconnected from life and real human interaction?

Is it the pharmaceutical companies that offer so many drugs for depression and anxiety, and then peddle other drugs if the frst drugs don’t work? I love how part of the disclaimer for a lot of these antidepressants is, “May cause suicidal thoughts.” Are they f*cking kidding me??

We now know that a young mind isn’t fully formed until around the age of twenty-four. And if that brain is under the infuence of these drugs, it may not be able to handle the full side effects. David was twenty-one when he died from a pharmaceutical drug overdose. I still don’t know who his psychiatrist was. F*cker.

Clearly, I have some anger issues to deal with.

Is suicide the last and only option when a tender heart is too broken to heal? Is that what happened with my David?

I don’t have the answers. And try as I might, I will never know what was going through David’s mind as the night of July 24, 1988, closed in.

But here’s what I do know. I know that my family structure was never solid. And it began to unravel around the time of my father’s death.

I know that living in isolation, even while (and maybe especially while) living under the same roof with many family members, destroys the soul.

I know that secrecy was rampant in my family. Still is. I know that I get very scared as I walk around my city of New York, witnessing person after person hunched over, their eyes locked like a zombie’s on their glowing screens. Unable or unwilling to peer up and risk looking around at what’s happening right in front of them. Not taking the chance to look another human being in the eye.

It terrifies me when I see a two-year-old, four-year old, ten-year-old glued to their phone or tablet while in a stroller or in a restaurant dining with their family. No social skills learned. No needing to learn how to behave respectfully in public, or how to gauge human behavior around them. Just placated and soothed by another world that gleams from their screens.

Talk about isolation.

I call it the new AA. Apple Anonymous. But here’s the thing: where there’s life there’s hope.

And the hope lies in knowing that I’m not alone in thinking this way. I’m not the only one who despairs over the lack of human connection that seems to be the new normal.

There’s hope in knowing that there’s more research, tests, and knowledge around pharmaceutical drugs and how they affect the mind.

I garner hope when I see people dining and having a conversation at a restaurant with no cell phones sitting on their table.

Hope rises when a smile is shared between me and a stranger as we pass each other on the street on a cool, crisp, sunny autumn day in NYC.

My heart is lifted with hope when precious time is spent with a close friend, as we muse over ways we can inspire more human connection through art.

And those two million people who reach out for help every year—I pray that every single one of them receives a seed of hope that will be planted deep in their hearts. Tended to. Nurtured and protected. So that in time, they will experience the strength in knowing that they belong here in this world. Come what may.

I hope they will know that they are already loved. Even though sometimes it feels like they aren’t.

They aren’t alone.

We aren’t alone.

We are already loved.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

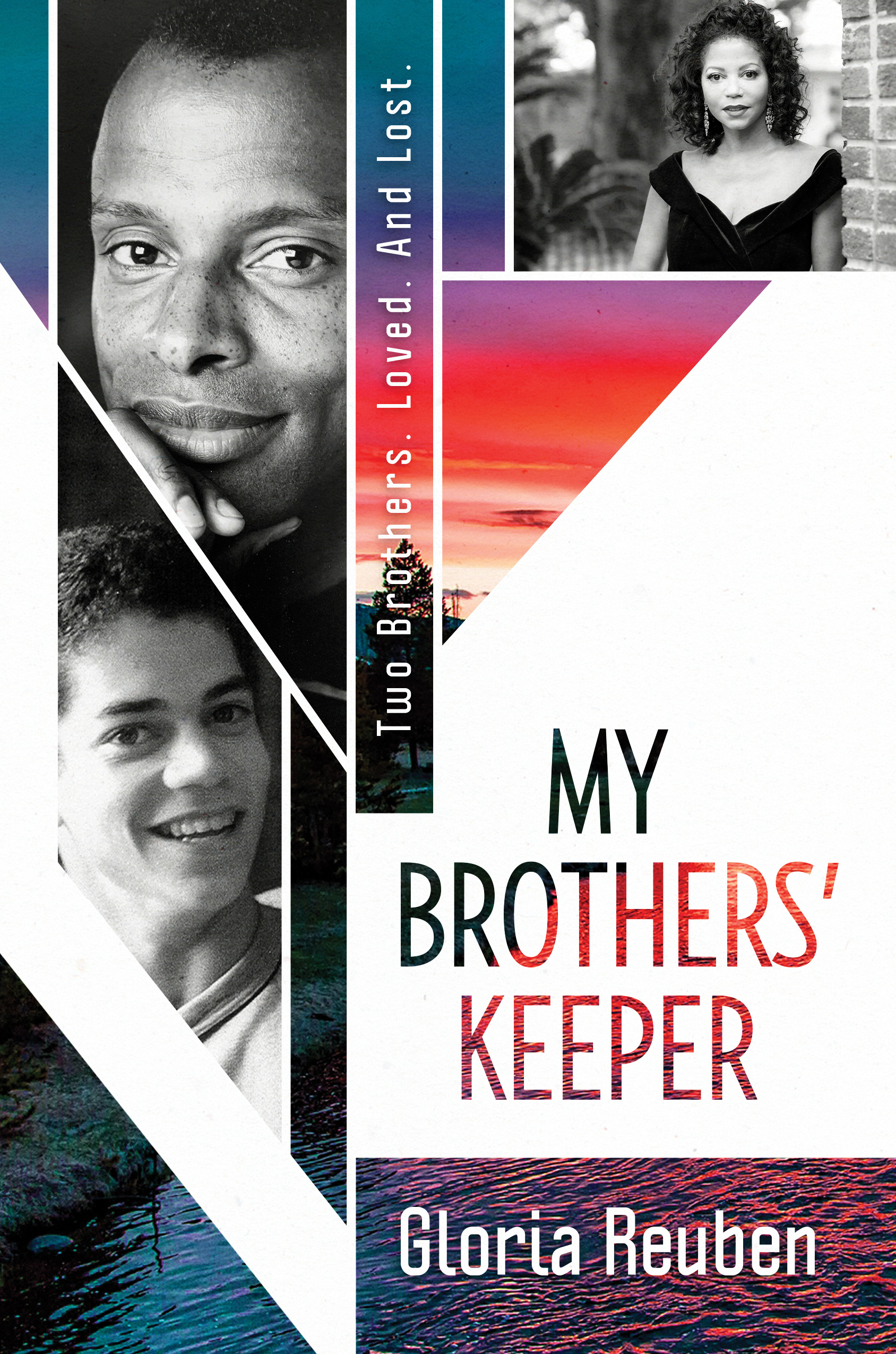

Excerpted from My Brothers’ Keeper: Two Brothers. Loved. And Lost. by Gloria Reuben. Used with Permission of Post Hill Press.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.