This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go here.

There are many ways in which Congress falls short of representing the American population. For example, 22% of members of the 116th congress are racial or ethnic minorities, even though non-whites are 39% of the country. Women are approximately 25% of congress, despite being 51% of the population. But perhaps the most remarkable identity difference between members of congress and the country they represent is on a different axis: education. 5% of members of congress do not have a 4-year college degree. 65% of Americans do not have a 4-year degree. Of course, we know that persons without a college degree are scarcely found in a broad range of lead institutions—including courts, newspapers, universities—where consequential decisions are made, or where the ideas and stories that inform those decisions are articulated.

Now there are many reasons, some good, for this discrepancy. We may want our elected leaders to be well educated, presuming that that education provides wisdom and perspective that has utility in governance. We know that to have a career in universities or media organizations one has to have gone to college, both to achieve the credentials that have one accepted into the relevant “guild”, and simply because everyone in those institutions does, making this a required “badge” for admission.

I am not here to argue whether this is the right way for us to structure our society, and we know that there are patently unfair reasons why some people end up being able to graduate from college while others do not. It does seem to me, however, that there are plenty of arguments that can be made for the importance of representation of all members of society in important sectors that fundamentally shape how we think and what we do collectively.

Let us take for example this moment in time. Imagine that we were, as a country, struck by a previously unknown disease, and we had to make choices about how to handle that disease that had a differential effect on persons based on their education. Would we then be confident that a congress that essentially has no members who have less than a college degree can make decisions that affect the two-thirds of the country who do?

The believers among us—and generally speaking as an immigrant who chose to be in this country I prefer to believe—might suggest that, yes, absolutely. Those who are in a position to determine what gets done and when will make sure that their particular group is not overly advantaged and they will work hard to ensure that all are looked after, and that the burden of the disease will not fall disproportionately on those who are not represented at these levels.

Is that what happened? For better or worse we have been living through just such a moment, the COVID-19 moment. To what extent did COVID-19 disproportionately affect those without a college degree, who were, perhaps, not represented when decisions were made—at all levels—about how we handle the virus and the trade-offs we needed to make that influenced our life?

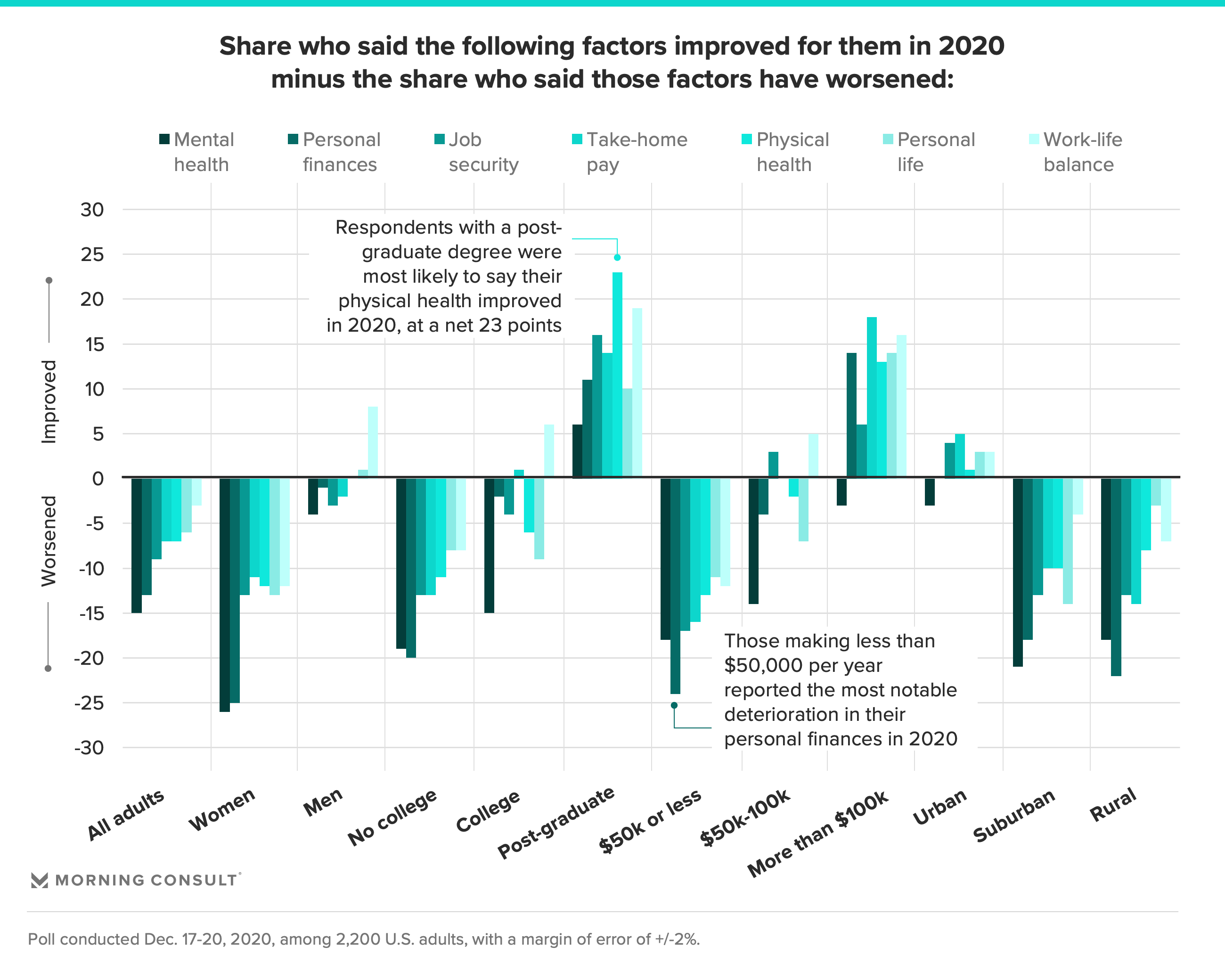

I could answer this in many ways, but let us look just at one graph, below

Leaving aside for a moment the criticisms that one can level at any set of data, and that I have little enough information about the methods behind this survey to be able to evaluate it fully, these data, from Morning Consult, tell a story that is corroborated by any number of sources. Fundamentally the picture is straightforward—the principal axis on which we have differentiation of COVID consequences is education. In fact, remarkably, those with post-graduate degrees reported an improvement in mental and physical health, personal finances, job security, pay, personal life, and work-life balance during COVID-19. Not surprisingly this coincides with persons with an income of more than $100,000 a year which, of course, is more concentrated among persons with higher educational levels.

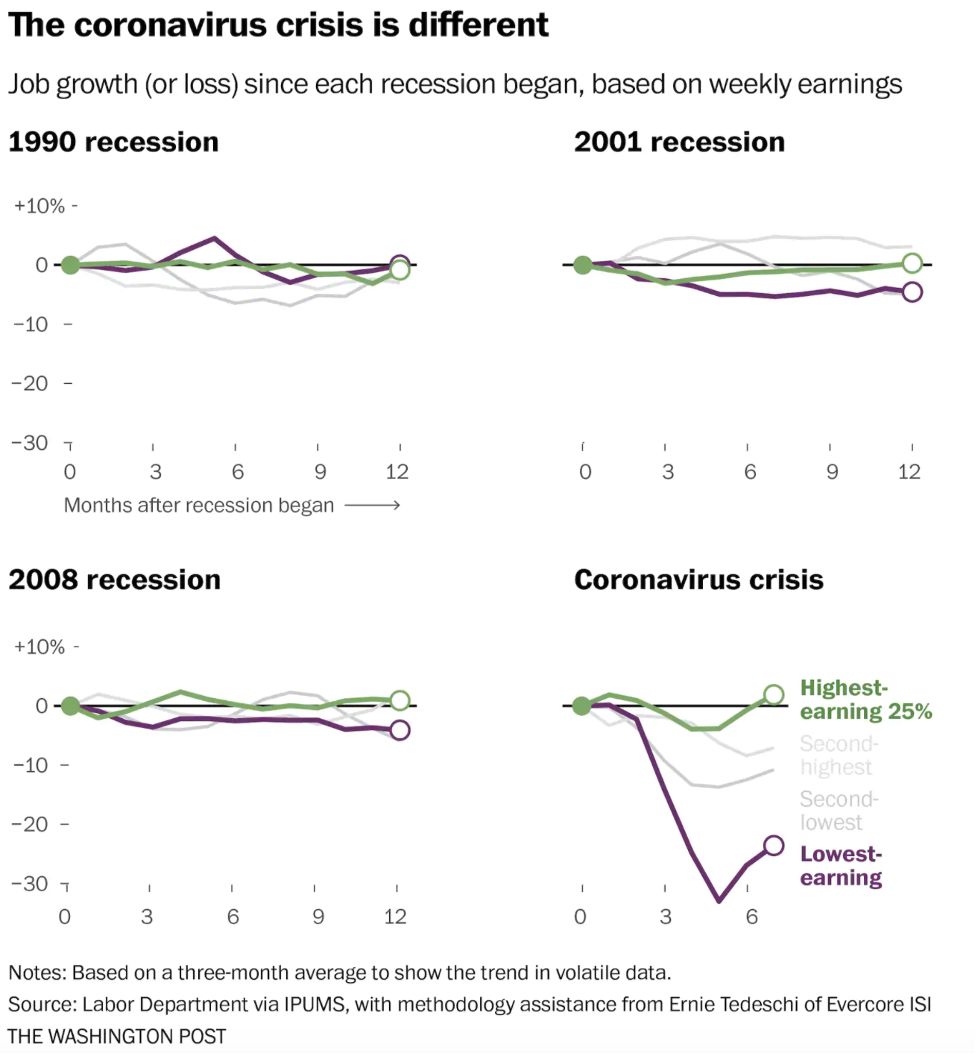

So, we went through a year of COVID-19 and those of us with higher education emerge better than we did before COVID-19, while everyone else is patently worse. Is this so surprising? COVID-19 resulted in an economic downturn that has been unparalleled in 90 years, with tens of millions of persons becoming unemployed during the pandemic. But that burden was not borne evenly—far from it. While economic capacity had recovered by October for those with high wages, it remained about 20% below where we started for those with low wages. This was, importantly, in sharp contrast with prior economic downturns. The graph below, fromThe Washington Post, makes this point well.

No recent recession resulted in more differentiation between persons who were high earning and low earning. Other economic recessions have affected us much more equally. And this comes at a time when our health has been diverging on axes of income and education more than ever before. In recent work, our team showed, for example, that the health of those in the richest 20% has substantially diverged from those in the poorest 80% over the past 20 years. And we know that much of this is highly correlated with race and ethnicity, with people of color vastly over-represented in the categories that were disproportionately affected than were white Americans.

So, what happened? Well, the pandemic hit, we were afraid—reasonably—we bungled testing and early response, leading us to adopt widespread shutdowns as a way of minimizing viral spread. And then we continued to bungle our response, and the shutdown efforts affected sectors that were over-populated by persons with lower levels of education and income: retail, service, hospitality, leisure, mining. Meanwhile, those of us with higher educations, and incomes, were able to spend more time at home, minimizing commute, perhaps working a bit less, and spending more time with our families. And more of our money is tied up to retirement accounts and other sources of wealth that are lined to the stock market, which has gone up, remarkably so.

I come back to where I started. Was what happened during COVID-19 inevitable? Looking at the past year at this point, when we are still in the throes of the virus, I can imagine anyone asking: but what else could we have done? Given our efforts to reduce infectious disease spread, was reducing contact not the only way? And that such an effort resulted in worse circumstances for some is perhaps regrettable, but maybe unavoidable?

I am not so sure. None of this minimizes for a second the imponderably high toll of COVID-19. But ultimately, what we do is always a matter of choices and trade-offs. A set of unprecedented circumstances resulted in a rapid surge in fear of disease—affected by a health system that was ill prepared for a rise in respiratory disease cases and a rapidly overwhelmed and vastly underfunded public health system—pushing us to take drastic measures that seemed like the only thing we could do. These measures perhaps may have seemed not so bad compared to COVID-19, particularly as those of us who make such decisions, and who are adjacent to those who do make such decisions, were actually doing just fine.

Would we have made different decisions were those who have less education, lower incomes, at the decision-making tables? It seems to me plausible that we would have, and we would now. Would we have invested many more resources in making sure we had tests available quickly if we knew that our own jobs were on the line if we did not succeed in that? Would we have left no stone unturned to make sure that we developed the best possible case identification, contact tracing, isolation systems to contain the pandemic early if we knew how much this would affect our own personal circumstances? Would you make a different decision about, for example, choosing to continue curfews, if that meant that you would lose your job, or substantially have lower income, even if it meant increasing risk of virus transmission a bit? I suspect so, or at least the choice to do so would have been made with greater appreciation for the complexity of the situation.

We have not been helped in the past year by suggestions that we should blindly follow the science, as though the science offers solutions that are clear cut. The science offers ways to mitigate viral transmission, yes, but it says nothing about how we weigh the costs of that mitigation. That is a matter of values and weighing the difficult trade-offs that inevitably should shape what decisions we make about health. And those decisions are easy when we are making decisions that protect our health, while harming others. They are much harder when those who are balancing harms—greater risk of viral transmission vs. job loss for example—are genuinely heard.

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH, is Professor and Dean at the Boston University School of Public Health. His upcoming book, The Contagion Next Time, will be published in fall 2021. Subscribe to his weekly newsletter, The Healthiest Goldfish, or follow him on Twitter: @sandrogalea