As of late, a week doesn’t go by without yet another man in a position of power being accused of sexual aggression towards women, and in some instances towards other men.

The impact of these disclosures has been widespread and furious. The Twitter hashtag #MeToo has become the unifying rally cry for those who have been victimized by manipulative and controlling men in powerful positions. The accused are facing condemnation on social media, firing from jobs, loss of esteemed careers, and ruined marriages.

Typically, we don’t spend a lot of energy worrying about the wellbeing of the offender, preferring retribution to compassion. We hope the courts will provide the double benefit of an “eye-for-an-eye” type of punishment while simultaneously making our communities safer by punishing those who could do us harm.

Yet in the last couple of decades the field of psychology has brought us an abundance of research in the topic of forgiveness, helping us realize that it is in our interest to look beyond our desire to even the score. Counterintuitive as it may seem, we ought to be thinking about the wellbeing not only of the victim, but the offender as well. It is in society’s interest for offenders to do the hard work of self-forgiveness, because risks to the general public will be reduced, better serving our society as a whole.

To clarify, self-forgiveness does not exonerate offenders for the hurt they have caused. The harm to their victims can never be undone.

Psychologists studying the field of forgiveness emphasize that prior to forgiving oneself for causing pain to another person offenders must go through the non-negotiable process of fully and honestly admitting responsibility for hurting someone. The offenders cannot take shortcuts such as minimizing or rationalizing their hurtful behavior. They have to abandon any attempt to cope by using the defensive and more familiar techniques of hiding behind power, control or deflection of blame onto others. Nor can they use pseudo-forgiveness, a false forgiveness that resembles forgiveness but in actuality is a quick-fix route of selfishly trying to forget, deny or justify the hurt they caused.

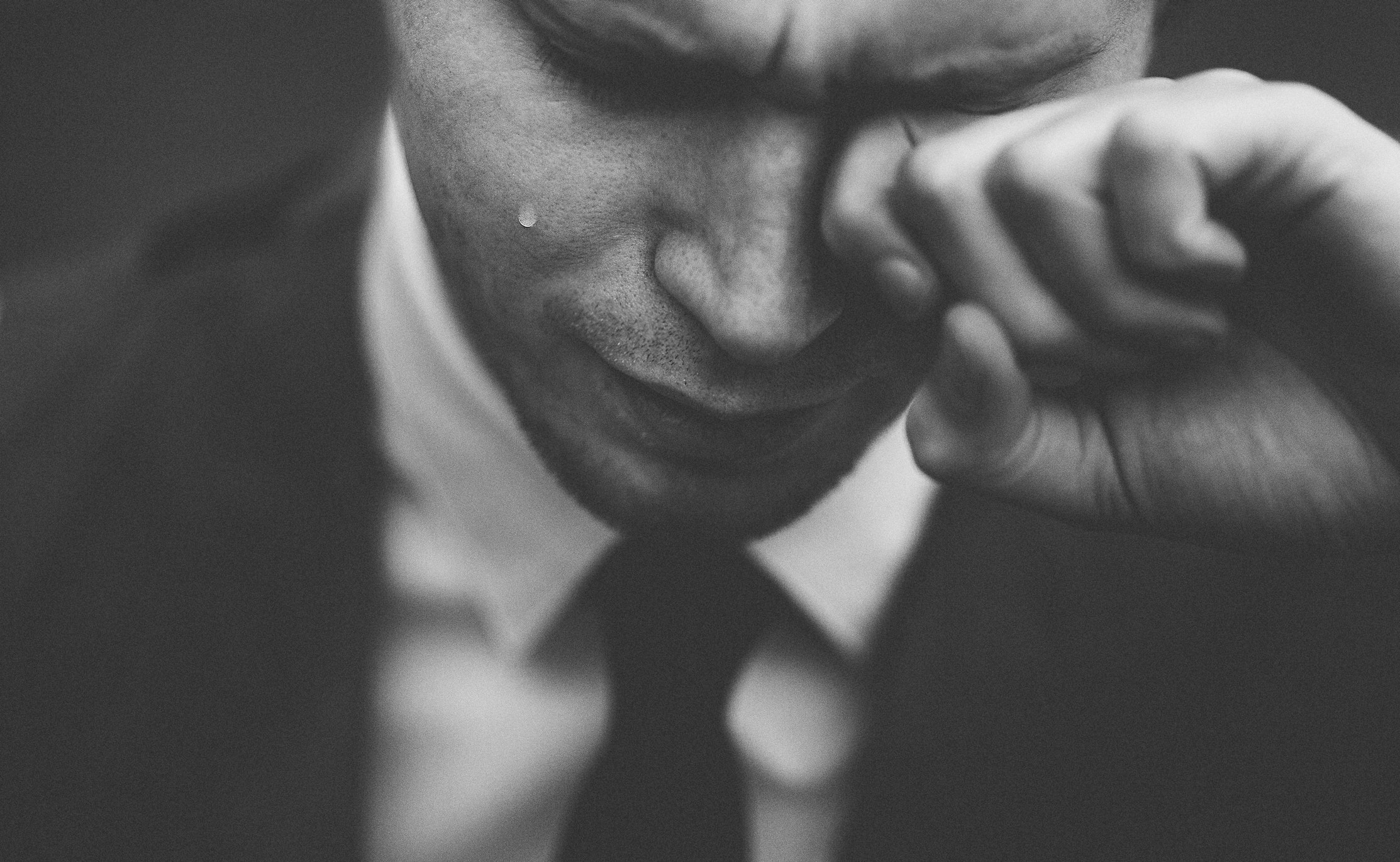

True self-forgiveness is hard work. It involves digging into the deep and dark feelings the offenders have resisted experiencing… up to now. Through this often lengthy, time-consuming self-exploration, offenders develop insights into why they did what they did. They realize why it was wrong to commit the hurtful acts, and that as a result of their actions, their lives and the lives of the victims are irrevocably changed.

From this process they can begin to own responsibility and create the pathway to becoming genuinely remorseful. At this point they will feel more motivated to make amends, either in the form of apology, restitution or both, to the victims. Giving back to the victims helps offenders develop compassion not just for those they hurt, but for others as well. Instead of feeling a sense of entitlement, which enabled their previous harmful treatment of others, the offenders can change and develop empathy for people.

On the other hand, when offenders do not take responsibility for hurting someone, or are overwhelmed by the recognition that their behavior was selfish and mean, they may find themselves stuck in a downward spiral of incapacitating feelings of worthlessness and shame. Research finds that the likelihood of these shame-based people inflicting pain on that same victim, or another person, continues to be a possibility.

If not resolved, shame lowers people’s self-esteem, which results in sleep disturbances, depression, loneliness and self-criticism. Doing what they can to escape those crushing feelings, they may attempt to self-medicate by turning to drugs, alcohol or other self-destructive behavior in an effort to shut down the emotional pain. Such self-destructive behaviors spill over into society as a whole, with considerable emotional and financial cost.

These offenders don’t live in isolation. Many have spouses and children. They cannot parent well when their emotional energy is depleted. The parent-child relationships may crack or even totally shatter because their toxic negativity, unhealthy values and coping skills are passed on to their children. These children and even their children’s children may grow up in pain, becoming innocent victims of an intergenerational crisis. Careers will stall, marriages collapse, and spirituality fray. Their immune systems may be stressed by living with chronic shame and anger, causing medical problems to develop, even resulting in premature deaths.

Rehabilitated offenders will recognize that their actions affected the careers, sense of safety, and emotions of others. By forgiving themselves, they change the direction of their lives. The prospect of permanently discontinuing the pattern of offenders hurting others and themselves can become a reality.