This is the third and last installment in a series about the work of psychotherapy pioneer Tim Beck. Read the first piece here and the second one here.

In one of Tim Beck’s recent articles, he tells the story of David, a 37-year-old man hospitalized with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

David’s symptoms are severe, and traditional therapeutic approaches have so far been unsuccessful. Some days it’s a challenge for him to even engage in a conversation.

One day, his therapist asks him what activity he liked most in the past. “McDonald’s,” he replies. “I’ve always enjoyed going to McDonald’s for a hamburger.”

The therapist proposes that they walk over to the hospital restaurant. On arrival, without explanation, a miraculous transformation occurs.

Suddenly, David is alert to his surroundings, able to cheerfully complete the transaction at the cash register and even to joke with the cashier before taking his food.

Had you been waiting behind David in line, you would never guess that he was suffering from a severe mental illness. But he wasn’t cured; once they left the restaurant, his schizophrenic symptoms returned.

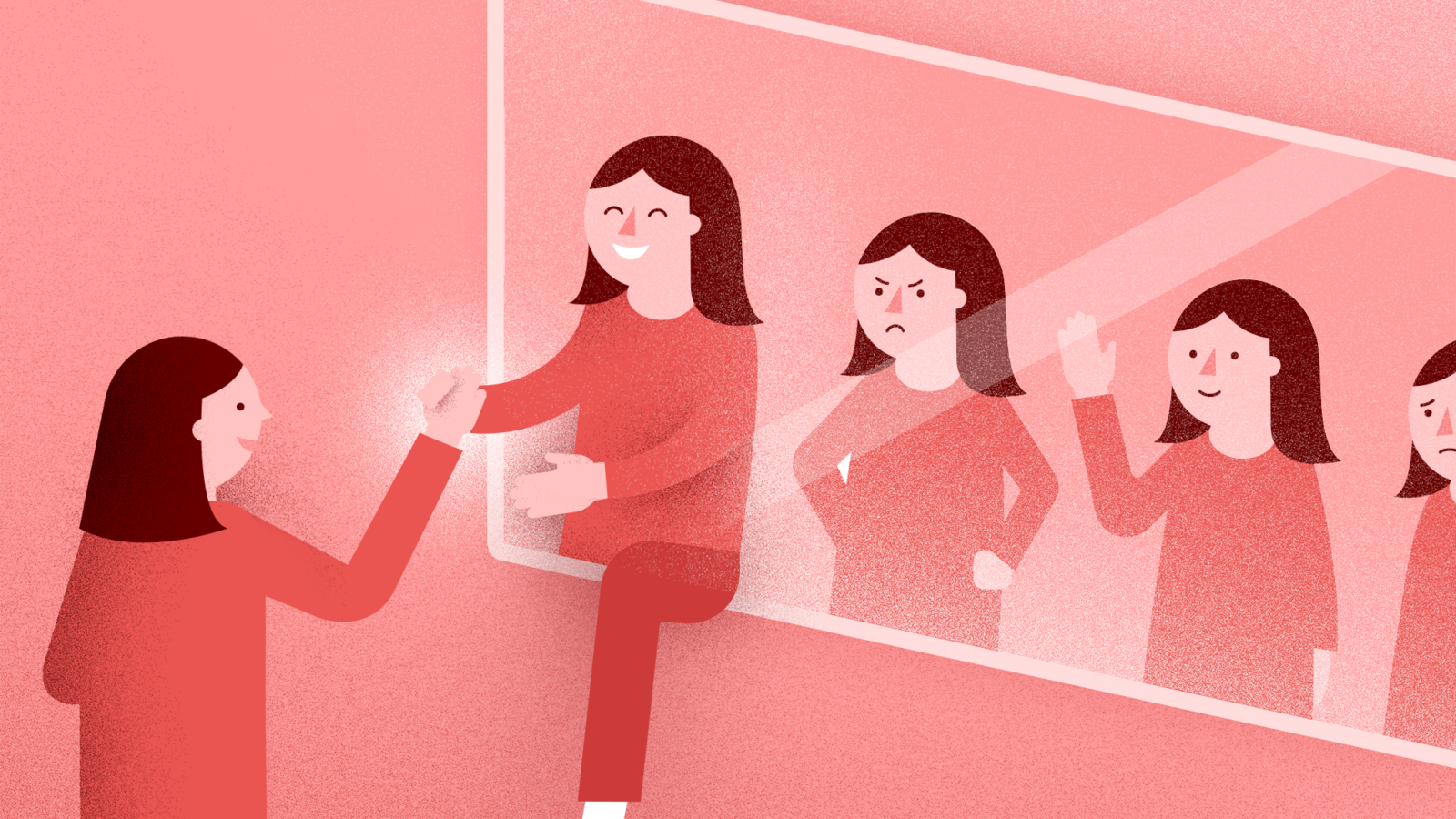

It was the observation of these strikingly different modes—co-existing personality states in the same individual—that inspired Tim to develop an alternative psychotherapeutic approach for patients who don’t improve in traditional cognitive therapy. And the implications of Tim’s Theory of Modes extend to all of us, not just those struggling with mental illness.

Rather than helping the patient correct maladaptive thoughts, this more recently developed approach is asset-oriented. The therapist, Tim explains, aims “to ferret out the individual’s values, interests, capacities, skills, [and] provide collaborative experiences that cater to these attributes and provide new learning.”

For instance, in the months following their visit to the restaurant, David and his therapist explored his interest in preparing and serving food, and together they discovered that the meaning of this particular interest was a deep desire to care for others. After learning to cook for himself, David learned to cook for other patients in the hospital, eventually leaving the hospital altogether to live on his own, with a full-time job at a restaurant.

Everyone, Tim says, has a profound need to feel accepted, respected, effective, and connected to others. “When individuals shift into an adaptive mode,” he says, “these critical needs and meanings in their lives can be met.”

Don’t dwell on your worst selves. In each of us coexist multiple modes—some more adaptive than others. Problematic behavior grabs our attention, but focusing on the positive is often more fruitful.

Do ponder, and perhaps share with the young people in your life, this parable, quoted verbatim from Tim’s recent article:

An old Cherokee is teaching his grandson about life.

“A fight is going on inside me,” he said to the boy.

“It is a terrible fight and it is between two wolves.

One is evil—he is anger, envy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego.”He continued, “The other is good—his is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith. The same fight is going on inside you—and inside every other person, too.”

The grandson thought about it for a minute and then asked his grandfather, “Which wolf will win?”

The old Cherokee simply replied, “The one you feed.”

With grit and gratitude,

Angela