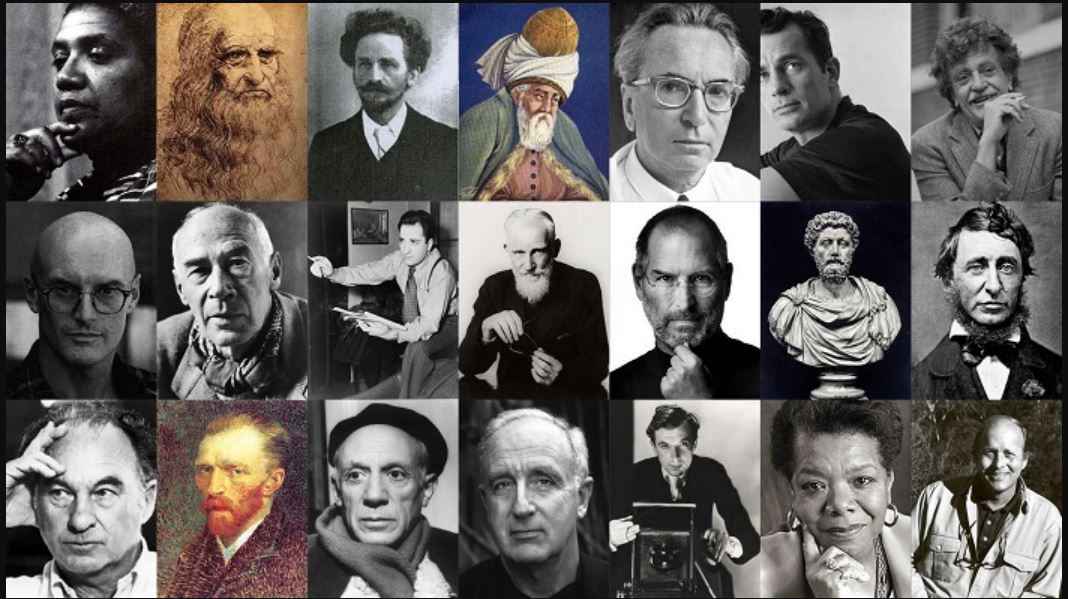

Some might claim the term “Genius” has been hijacked by our current society. When Kayne West and Kim Kardashian are called geniuses, or when the President ironically calls himself a “Humble Genius,” the term appears to have taken on a new connotation. It is more than a high IQ test score or academic achievement. One thing that is true with geniuses throughout time is that many of their ideas have been so forward-thinking that they often are not recognized until after their death. So the verdict is still out for the West family and the Donald in that they still could be remembered as geniuses in retrospect, but given the esteemed group they would be joining, I would bet against it.

Professor Craig Wright from Yale University has researched geniuses over time and in his book The Hidden Habits of Genius has discovered these key traits: Work Ethic, Resilience, Originality, Child-Like Imagination, Insatiable Curiosity, Passion. Creative Maladjustment, Rebellious, Cross Border Thinking, Contrarian Action, Preparation, Obsession, Relaxation, and Concentration.

I was fortunate enough to interview Professor Wright on a recent Podcast. I asked him what a person who is not a genius and may not have the time and patience to curate these 14 skill sets can learn from Lincoln, Einstein, or Shakespeare. I asked him if I could focus on just a few areas to maximize my time and energy to get just a taste of what these legendary icons experienced in their lives. Although the Professor was quick to point out that there are no short cuts, he did recommend these three areas for us mortals focus on to get a chance to tug on the robe of genius.

Cross-Discipline

The list of traits, habits, and experiences from Professor Craig mix together to create a rich soup for curating genius. At its heart, genius is based on the application of cross-disciplinary fields. A common phrase in the financial world is that diversification is free, and at no time in history has learning a new skill or subject area been this easy and affordable. Coursera has over 1600 free classes online, ranging from Artificial Intelligence, to learning a new language. Most of the major universities have all their course curriculum that includes class lectures, notes, and readings available online at no cost. Not only do Coursera and University repositories have great depth on specific subjects, but the content is also curated by the world’s eminent thought leaders in the area of study.

The application of cross-discipline knowledge and insights does not necessarily require mastery in these areas. The magic often is in the unique mix of these areas to create something unique. Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert, in his book How to Fail at Everything and still Win Big, felt a key to his success was his ability to combine his good but not great skills. Adams was a good cartoonist, he knew the business world and he was funny. He admits he is not the best cartoonist or smartest businessperson or even really all that funny, but he combined these skills into an extremely successful career.

Keep in mind that the new topic may be very distant from your Journey. If you are an AI researcher dusting off that guitar from high school and relearning the cords may seem silly and a waste of time but that is where the magic happens. The practical application of combining jamming on an electric fender and AI development might not be apparent, if it were, someone would have made the connection already.

There should be a genuine interest in these diverse areas. Forcing yourself to learn Sanskrit with the expectation that it will help you write your novel may not ever pay off. Learning a new skill or subject matter should be based on authentic curiosity in the topic area. Pursuing these other interests with the expectation of a miraculous connection to occur will likely guarantee that no insights will emerge. That would be like a meditator every day sitting down and demanding enlightenment. That is not the way these practices appear to work. Steve Jobs didn’t take the calligraphy class at Reed College with the plan of dropping out and applying this learning years later on the Macintosh that brought font type to the masses.

Build Downtime into your routine

If you are reading this article, it is highly likely that you have heard this advice before several times and have ignored it because you feel the grind of work will eventually pay off. “Lunch is for Wimps,” as Gordon Gecko famously said in the movie Wall Street. Heroes on their journeys are always looking to optimize, and the big area that can often be enhanced and intensified is time.

But many studies show that people need downtime to rest the mind and the body. It is in these downtimes that breakthrough ideas can occur. You often hear someone say they had a thought in the shower. It is so common it has become almost a cliché, but often epiphanies take place away from the digital screens and workplace. Showers are an especially common place for ideas because they are often taken in the morning when the internal critic is still groggy, so ideas flow more manageable. The shower is also a safe, quiet place with no expectations of creative production, and that is when it is most likely to strike. Professor Wright points out that many geniuses were famous for taking breaks, naps, or baths where they could step away from work and quiet the mind.

This is an area that many type A people overthink. They feel it is necessary for downtime to payoff to buy an expensive flotation tank, sleep pod, or hyperbaric chamber. Those devices may, in fact help, but if you consider the downtime as worktime it could be counterproductive. The goal should be to shut down with no expectation.

Redefine Failure

One thing key attribute that separates these geniuses from the rest of us is their perception of failure. Wright thinks these individuals almost had no choice and were compelled to pursue their journeys. This trait of plowing through setbacks has been played up in books like Grit, but of the three genius hacks, this is the most challenging muscle to build. Challenges, setbacks, and all-out failures are often romanticized in the biographies of geniuses with the historical view of a victorious triumph. The reality is these failures are brutal and spirit crushing events. The fact that Michael Jordan did not make the cut for his high school basketball team appears almost funny through the lens of history. But for a young Michael Jordan this was a crushing set back. The failure can be interpreted that the entire journey is a fools errand. Mike Birbigula a successful comedian, writer and actor often felt that his idea of being a standup comic might be just some grand ego driven delusion. This was not necessarily because of self-doubt in his skills but more from a total lack of progress and audience acceptance of his humor night after night

Winston Churchill is quoted that genius is going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm. The idea of not being bothered or discouraged by a significant humiliation is not a normal human reaction. Often an earnest effort on a project that flops appears to be the universe telling the journey taker to pack it in and buy some ice cream and watch Netflix. In this area, geniuses are probably most unlike ordinary people in that they are serial failure generators.

Having a different perspective can reduce the sting of these failures. Professor Wright tells us to, “imagine ourselves in a room with 500 doors when one door shuts just head to another. The most important thing is to keep moving forward.” In his last lecture at Carnegie Mellon, Randy Pausch pointed out “The roadblocks and barriers on your journey are not there to stop you. They are there to eliminate those who don’t want it as bad.” One mindset is to consider an attempt at something new as an experiment, a trial period to test out the results. Doing this can reduce the power and stigma of not succeeding. Success is a numbers game, so that multiple attempts can increase your surface area for success.

Articles on geniuses focus only on the achievements because people want to read about the spoils of the success, the private island, the luxury jet, not the long hours in desperate solitude alone at the computer or factory floor. We only see the tip of the iceberg of success and not the messiness it took to get there. To think that someone we have made a statue of or carved their image on a mountainside had sleepless nights, deep regrets, and times of deep despair is difficult to imagine. The reality is that this is part of the ride and the odds of being successful without incidents of deep disappointment is not realistic. These times of trouble are critical in the recipe for outstanding achievement. With geniuses, the grind and getting back up after being knocked down is more important than IQ and may be the critical element that separates these iconic humans from the rest of us.