Could right now be the most influential time ever? Richard Fisher looks at the case for and against – and why it matters.W

What is the best word to describe our present moment? You might be tempted to reach for “unprecedented”, or perhaps “extraordinary”.

But here’s another adjective for our times that you may not have heard before: “hingey”.

It may not be a particularly elegant term, but it describes a potentially profound idea: that we may be living through the most influential period of time ever. And it’s about far more than the Covid-19 pandemic and politics of 2020. Leading philosophers and researchers are debating whether the events that occur in our century could shape the fate of our species over the next thousands if not millions of years. The “hinge of history” hypothesis proposes that we are, right now, at a turning point. Is this really plausible?

The idea that those alive today are uniquely influential can be traced back several years to the philosopher Derek Parfit. “We live during the hinge of history,” he wrote in his book On What Matters. “Given the scientific and technological discoveries of the last two centuries, the world has never changed as fast. We shall soon have even greater powers to transform, not only our surroundings, but ourselves and our successors.”

The hinge of history hypothesis has been gaining fresh attention in recent months, however, as academics attempt to address the question in a more systematic way. It began last year when the philosopher Will MacAskill of Oxford University posted an in-depth analysis of the hypothesis on a popular forum dedicated to effective altruism, a movement that aims to apply reason and evidence to do the most good. It sparked more than 100 comments from other scholars approaching the question from their own angle, not to mention in-depth podcasts and articles, so MacAskill published a more formal version, as a book chapter in honour of Parfit.

As Vox Future Perfect’s Kelsey Piper wrote at the time, the hinge of history debate is more than an abstract philosophical discussion: the underlying goal is to identify what our societies should prioritise to ensure the long-term future of our species.

To understand why, let’s start by looking at the arguments that support the present moment’s “hingeyness” (though MacAskill now prefers the term “influentialness”, as it sounds less flippant).

First, there’s the “time of perils” view. In recent years, support has grown for the idea that we live at a time of unusually high risk of self-annihilation and long-term damage to the planet. As the UK’s Astronomer Royal Martin Rees puts it: “Our Earth has existed for 45 million centuries, but this century is special: it’s the first when one species – ours – has the planet’s future in its hands.” For the first time, we have the ability to irreversibly degrade the biosphere, or misdirect technology to cause a catastrophic setback to civilisation, says Rees, who co-founded the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge.

Story continues below

In front of posters about the Sars epidemic, a boy eats ice cream, which we collectively spend more on than preventing extinction through our technology (Credit: Getty Images)

Those destructive powers are outstripping our wisdom, according to Toby Ord – one of MacAskill’s colleagues at Oxford – who makes the case for reducing existential risk in his recent book The Precipice. The title of Ord’s book is an allegory for where we stand: on a path on the edge of a precipice, where one foot wrong could spell disaster. From this vertiginous point, we can see the green and pleasant lands of the destination ahead of us – a flourishing far future – but first we must navigate a time of unusual danger. Ord put the odds of extinction this century to be as high as one in six.

In Ord’s view, what makes our time particularly hingey is that we have created threats that our ancestors never had to face, such as nuclear war or engineered killer pathogens. Meanwhile, we are doing so little to prevent these civilisation-ending events. The UN Biological Weapons Convention, which is a global ban on developing bio-weapons like a super-coronavirus, has a smaller budget than an average McDonald’s restaurant. And collectively the world spends more on ice cream than we do on preventing technologies that could end everything about our way of life.

The UN Biological Weapons Convention, a global ban on developing bio-weapons like a super-coronavirus, has a smaller budget than an average McDonald’s restaurant.

The idea that we are at a treacherous turning point is also the theme of a second argument supporting the hinge of history hypothesis. According to a number of serious researchers, there is the chance that the 21st Century will see the arrival of sophisticated artificial general intelligence that could quickly evolve into a superintelligence. They argue that how we handle that transition could determine the entire future of civilisation, through a kind of “lock-in”.

The all-powerful superintelligence itself could determine humanity’s fate for all time, based on whatever goals and needs it has, but these researchers propose other potential scenarios too. Civilisation’s future could also be shaped by whoever controls the AI first, which might be a single force for good who directs it for the benefit of everyone, or a malevolent government who chooses to use that power to subjugate all dissent.

Not everyone subscribes to AI’s long-term influence. But those who do counter that even if you believe there is only a small chance of the worst-case AI scenarios happening, the fact that they could be so influential for such a very long time could make the coming decades more important than any in human history. For that reason, many researchers and effective altruists have decided to dedicate their careers to AI safety and ethics.

We stand at a precipice, where the future is visible but the path is treacherous (Credit: Getty Images)

You could also assemble other evidence to support the hinge of history hypothesis. For example, Luke Kemp of the University of Cambridge points out that human-caused climate change and environmental degradation in this century could reach far into the future. “The most pivotal transformation so far in human history was the advent of the Holocene, which allowed for the agricultural revolution,” says Kemp. “Human societies appear to be intimately adapted to a narrow climatic envelope. This is the century in which we will perform an unprecedented and dangerous geological experiment and perhaps irreversibly push ourselves well outside of the climate niche, or pull back from the abyss.” (Though it should be noted that Kemp himself is sceptical about the hypothesis and its expedience.)

You might also argue that civilisation’s relative youth makes us particularly influential. We’re only 10,000 years or so into human history, and a case could be made that earlier generations have a greater ability to lock changes, values and motivations that persist for later generations. We might think of civilisation today as a child who must carry both formative traits and scars for the rest of their lives.

Though as we’ll see, our relative youth could also be used to argue the opposite. And this also raises an obvious question: surely, then, the first humans lived at the most influential time? After all, a few wrong steps in the Palaeocene, or at the dawn of the agricultural revolution, and our civilisation would never have come into existence.

Perhaps, but MacAskill suggests that while many moments in human history were pivotal, they were not necessarily influential. Hunter-gatherers, for example, lacked the necessary agency to sit at the hinge, because they had no knowledge that they could shape the far future, nor the resources to choose a different path if they did. Influence, under MacAskill’s definition, involves an awareness and ability to choose one of myriad paths.

Why it matters

This specific definition of influentialness leads on to why MacAskill and others are interested in the question in the first place. As a philosopher who thinks about the far future, MacAskill and others see the hinge of history hypothesis as more than a theoretical question to satisfy curiosity. Finding answers affects how much resources and time they believe that civilisation should spend on near-term versus longer-term problems.

To give this a more personal framing, if you believed that the next day of your life would be the most influential so far – taking a crucial exam or marrying a life-partner, for instance – then you’d put a lot of time and effort into it straight away. If, however, you believed the most influential day of your life was decades away, or you didn’t know what the day would be, you might focus on other priorities first.

A wildfire cloud looms over Californian traffic, earlier this month (Credit: Getty Images)

MacAskill is one of the founders of effective altruism, and has focused his career on finding ways to do the most good over the long-term. If an effective altruist accepted that we are at the hingiest time now, then it might suggest devoting a large proportion of their time and money to reducing existential risk urgently, for example – and indeed, many have.

If, however, that altruist believed that the hingiest time was centuries away, then they might pivot to other ways to do good over the long-term, such as investing money to help their descendants. A philanthropist, for example, who invested at a 5% rate of return could see their resources grow by 17,000 times after 200 years, according to MacAskill.

Some might question this assumption about the benefits of long-term investment, given that societal collapses throughout history have wiped out funds. While others might suggest that money would be best spent on big present-day problems like poverty. But the essential point for effective altruists is that nailing down hingeyness could at least help to inform how we might maximise well-being as a species and ensure we flourish in the future.

Against hinginess

So, if those are some of the arguments for the hinge of history hypothesis, and the reasons why it matters, what are the arguments against?

The simplest comes down to fairly straightforward odds. Probability-wise, it’s just unlikely.

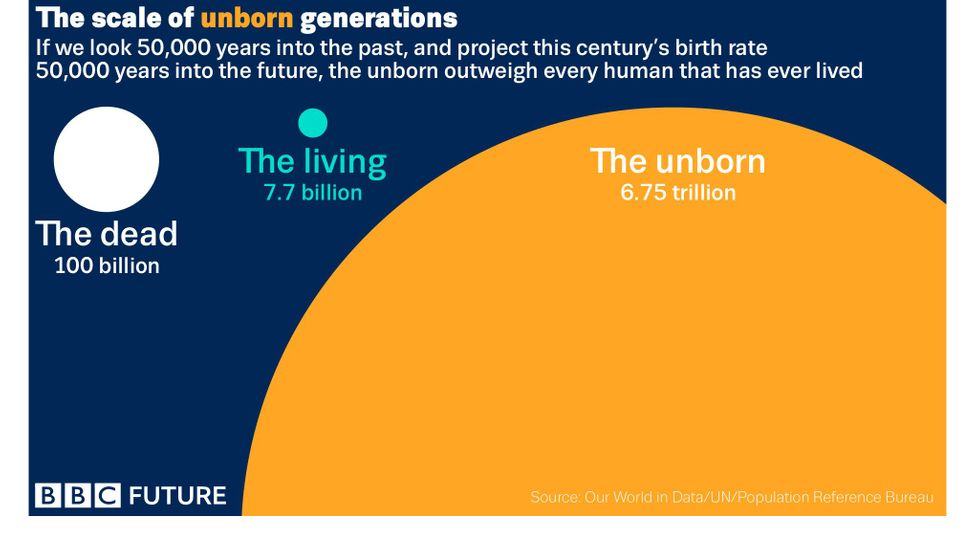

If we were to navigate past this century and reach the average lifespan of a mammalian species, then we’re talking about humanity lasting at least one million years, in which we could potentially spread to the stars and settle other planets. As I wrote on BBC Future last year, there are potentially a vast number of people ahead of us, yet to born. Even if we look at only the next 50,000 years, the scale of future generations could be enormous. If the birth rate over that period stayed the same as it has been in the 21st Century, the unborn would be potentially more than 62 times the number of humans that have ever lived, around 6.75 trillion people.

(Credit: Nigel Hawtin)

Given the astronomical number of people yet to exist, says MacAskill, it would be surprising if our tiny fraction of that population happens to be the most influential. These future people will likely (hopefully) also be more morally and scientifically enlightened than we are today, and therefore could potentially do even more to influence the future in ways we can’t yet conceive of.

It’s not only unlikely, MacAskill continues, it’s also possibly “fishy”. Those who conclude we must live at the hinge of history might be deploying hidden faulty reasoning; an unconscious stacking of the deck. What if cognitive biases are at play, for example? Firstly, there’s salience bias, which makes visible, present-day events seem more important than they actually are. Living in the 1980s, for example, you might have thought that nanotechnology was the greatest risk to humanity, but the much-feared “gray goo” theory turned out to be over-hyped.

If a chain of reasoning leads us to the conclusion that we’re living at the most influential time ever, we should think it more likely that our reasoning has gone wrong

Secondly, there’s potential for confirmation bias: if you believe that existential risks deserve more attention (as all the researchers in this article do), then you might subconsciously marshal arguments that support that conclusion.

“If a chain of reasoning leads us to the conclusion that we’re living at the most influential time ever, we should think it more likely that our reasoning has gone wrong than that the conclusion really is true,” writes MacAskill.

For these reasons, among others, MacAskill concludes that we are probably not living at the most influential time. There may be compelling arguments for thinking we live in an unusually hingey moment compared with other periods, he suggests, but because of the potentially long, long future of civilisation that could lie ahead, the actual hinge of history is most likely yet to come.

The upside of no hinge

While it might seem deflating to conclude that we are probably not the most important people at the most important time, it could be a good thing. If you believe the “time of perils” view, then the next century will be especially dangerous to live through, potentially requiring significant sacrifices to ensure our species persists. And as Kemp points out, history suggests that when fears are high that a future utopia is at stake, unpleasant things are sometimes justified in the name of protecting it.

“States have a long history of imposing draconian measures to respond to perceived threats, and the greater the threat the more severe the emergency powers,” he says. For example, some researchers who wish to prevent the rise of malevolent AI or catastrophic technologies have argued we may need ubiquitous global surveillance of every living person, at all times.

But if life at the hinge requires sacrifices, that does not mean that life at other times can be laissez-faire. It doesn’t absolve us of all responsibility to the future. This century we could still do remarkable damage, and it needn’t be as catastrophic as a species-ending event. Over the past century, we have found myriad new ways to leave malignant heirlooms for our descendants, from carbon in the atmosphere to plastic in the ocean to nuclear waste beneath the ground.

So, while we do not know if our time will be the most influential or not, we can say with more certainty that we have increasing power to shape the lives and well-being of billions of people living tomorrow – for better and for worse. It will be for future historians to judge how wisely we used that influence.