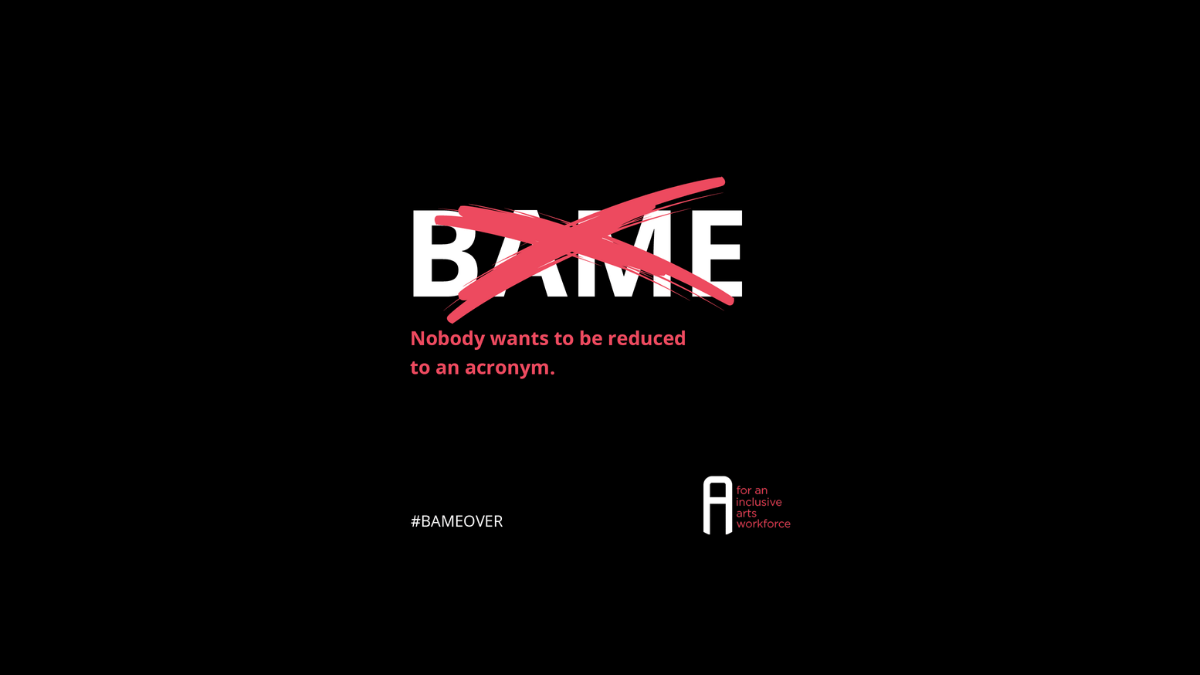

I write this with a heavy heart. When I first read this #BAMEOver statement it made me realise something that I hadn’t really taken the time to explore fully until now. I am someone who has used the term BAME in my vocabulary in the past. I used it without even batting an eyelid – not realising why grouping us together like this isn’t helpful. When I say ‘us’ I mean those who identify as being ethnically diverse.

BAMEOver is a statement for the UK. In August more than 1000 people completed a survey conducted by Inc Arts. On 4th September 2020 over 250 people came together to reset the terms of reference for people with lived experience of racism.

Essentially this document provides guidance on the terms to use instead of BAME. The very last paragraph states:

The difference between saying ‘BAME’ and ‘people of South Asian heritage’ or ‘people who experience racism’ is approximately 2 seconds. 2 seconds is not too much time to devote to taking positive anti-racist action on a daily basis. Remaining actively conscious of the language we use is a powerful act of allyship.

After reading this I felt a real sense of unease. I took the time to delve into why I didn’t think twice about the use of this acronym before – especially as someone who is British Indian – I was born in the UK and I am of Punjabi heritage.

At the risk of a possible backlash, I am going to openly state that I spent much of my youth shunning my roots. I grew up in a family where pretty much every single male ‘role model’ beat the sh*t out of their wives and if they weren’t beating the sh*t out of them, they were manipulative and controlling. There was also sexual abuse thrown into the mix. Please know that this is NOT indicative of the behaviours from those of my heritage. I understand that the cyclical behaviours in my family were passed down from generation to generation and why it never stopped – it was because it was all they knew. And this can and does happen in all cultures. However, when I discovered from two of my other peers at school that they were witnessing the same behaviours, I thought that’s it – it must happen in every Punjabi family.

My mum and dad’s marriage ended abruptly in the late 90s. Social services gave my mum 24 hours to decide whether she’d stay with my dad, or let us go into care. She chose us. Then we had to live in a women’s refuge for 3 weeks. At the age of 13 I was dealing with legal aid letters and helping mum sort through household bills because she could not read and write English. Over 20 years ago, my mum was one of few Punjabi women at the time to go through a divorce. Within a week of the split we were essentially deserted from both sides of the family. I witnessed how a lack of education – and freedom to make her own decisions – meant my mum did not live her true potential and I did not want that to happen to me.

I grew up knowing very little of British colonial rule of India, other than the anecdotes I heard about my maternal grandmother who with her family, had to suddenly leave their home because they lived on the wrong side of the border. In the panic to get on to trains out of the newly formed borders during Partition, my Bibi’s (we call my nan Bibi) younger sister died – she had fallen from a train in what was described to me as hysteria, where thousands of people were fleeing for their lives. I admit that I still don’t know everything about ‘The British Raj’ – a term used to describe Britain’s rule of India. My family had land to grow food but were not ‘cash rich’. All I grew up hearing from my parents, aunties, uncles and grandparents was that England was the place to be – to live better, more fulfilled lives and provided the chance for them to climb out of poverty. To be in England and be ‘English’ was a good thing. Remember this Goodness Gracious Me Sketch?

At school I was referred to as ‘coconut’ by my Indian counterparts – “brown on the outside white on the inside” – because I had a non-Indian forename and couldn’t speak Punjabi (I didn’t start speaking until I was 6 and speech therapists told my mum that I was confused so she should only speak to me in English. I wasn’t confused I just chose not to talk but that’s another story for another day).

This next admission may cause yet more backlash. I leveraged the fact I was given a ‘western’ name, despite being picked on about it as a child. I also leveraged having fair skin. This thought process used to go through my mind when sending CVs to gain work experience in the broadcast industry over 15 years ago: “They won’t know I’m Indian – my surname only has 3 letters – they’ll think I’m ‘English’ and if I get an interview, when they see me, they (hopefully) won’t be able to tell that I am actually Indian.” I never consciously questioned why I thought my heritage would be an issue and why being perceived as ‘white’ would help me ‘get on’ in the industry. At the time – in the words of Tupac Shakur – “That’s just the way it is” was my ‘way of living.’

I was once loved by people whom I considered as family and they are of European ancestral origin. I am loved by friends of European ancestral origin. These friends give me joy, support and love in abundance, as do my friends from other heritage backgrounds of course! I am lucky to have them all.

I am also someone who has never been on the receiving end of racism. No malicious behaviour or rhetoric has ever been directed towards me personally about my ethnicity. Is this because of my non-Indian forename, my fair skin, how I behaved and who I surrounded myself with? I don’t know. I have, however, been in situations where what has been discussed with me about my heritage has been rooted in ignorance with remarks like: ‘When the Indian’s came over we thought their women were good looking at least. And to be fair you’re a very good looking woman yourself.‘ I think they were attempting to be complimentary but I didn’t settle for days after this.

I grew up truly grateful for being born in the UK, because I was able to have more opportunities than my mum. And I still am grateful. I think about how lucky I am to live in the UK Every. Single. Day. So with all this – and there is so much more but then this blog would turn into a book! – the shunning of my heritage and hoping to ‘get away’ with being identified as being ‘English’, meant I had never before questioned the label BAME. In a weird way I didn’t attribute myself as being part of this group because I never felt ‘Indian’ enough, but there again I never felt ‘English’ enough either.

I shared the #BAMEOver document with a number of people of African, Caribbean and South Asian heritage who work within the UK broadcast industry, to get their thoughts on this. Here’s what was shared with me anonymously:

“The term seemed to appear from nowhere and became standard. I think that it diminishes racial differences and is disrespectful.”

“It’s a great document and I felt better after reading it. I am guilty myself of NOT KNOWING WHAT I WANT TO BE CALLED! What’s my label?”

“I see myself as an individual working in favour of a collective sense. I identify myself as a Black British man and honoured by that right. I don’t identify with saying I’m Caribbean, because that is not my full identity but then I understand how that part of me has had an influence on my life. I truly think it’s your given right to be identified how you see fit and acknowledge or come to terms with your existence in the world – specifically knowing what your role is and how you rule from your disposition.”

“The word BAME is now considered inappropriate and people are getting angry about its use. I believe a re-education plan needs to be to executed. There was a time when ‘coloured’ was acceptable and now it’s not! So… there is an amount of work to do to ensure that people understand that Black people are no longer happy to be put into a box with other people of colour. However, I can’t help but wonder if my Asian friends or colleagues feel like they are being left out?”

I keep reading what I have written here over and over again because I fear what the response to this will be. Will I be judged? Will I be hated for admitting the things I have? Will I regret being this open and honest? Will I become completely unemployable? On the flip side will this be ignored? Will it roll on by like tumbleweed?

But then I continually ask myself; what is it that I want to happen as a result of writing this? The answer is that I want to make a positive difference, in whatever way I can, to highlight the changes needed in the language we use around describing groups of ethnically diverse people.

I want to share one last quote from an email I was sent about the #BAMEOver document.

“My children are of mixed heritage and I constantly correct people for calling those of mixed ethnicity “Mixed Race”! It is my understanding that there is only one race of people on this planet and they are humans!”

I concur. I certainly don’t want to dismiss the importance of #BAMEOver or the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter Movement. It is vital that we acknowledge the wrongs of the past to make it right for the future and embrace our differences as human beings.

My nephew recently turned a year old and he is of mixed heritage. His mother is Welsh and grew up in England. This little boy has lit up my life in a way I did not imagine possible. I love him sooooooo much. It is my hope that we as a human race always act from a place of love, empathy and compassion for one another, so that my nephew never faces the identity crisis I grew up with. Throughout my life many strangers along my travels have tried to place me in a group of people (not with racist intentions, more out of curiosity), and the typical question I get asked is ‘Where are you from? Are you Italian, French, Spanish, Armenian, Persian, Argentinian, Chilean, Brazilian?’ There is a part of me that likes the fact that I can’t be placed because the most important thing for others to acknowledge is that:

I am human and I’m from planet earth.