Welcome to our special section, Thrive on Campus, devoted to covering the urgent issue of mental health among college and university students from all angles. If you are a college student, we invite you to apply to be an Editor-at-Large, or to simply contribute (please tag your pieces ThriveOnCampus). We welcome faculty, clinicians, and graduates to contribute as well. Read more here.

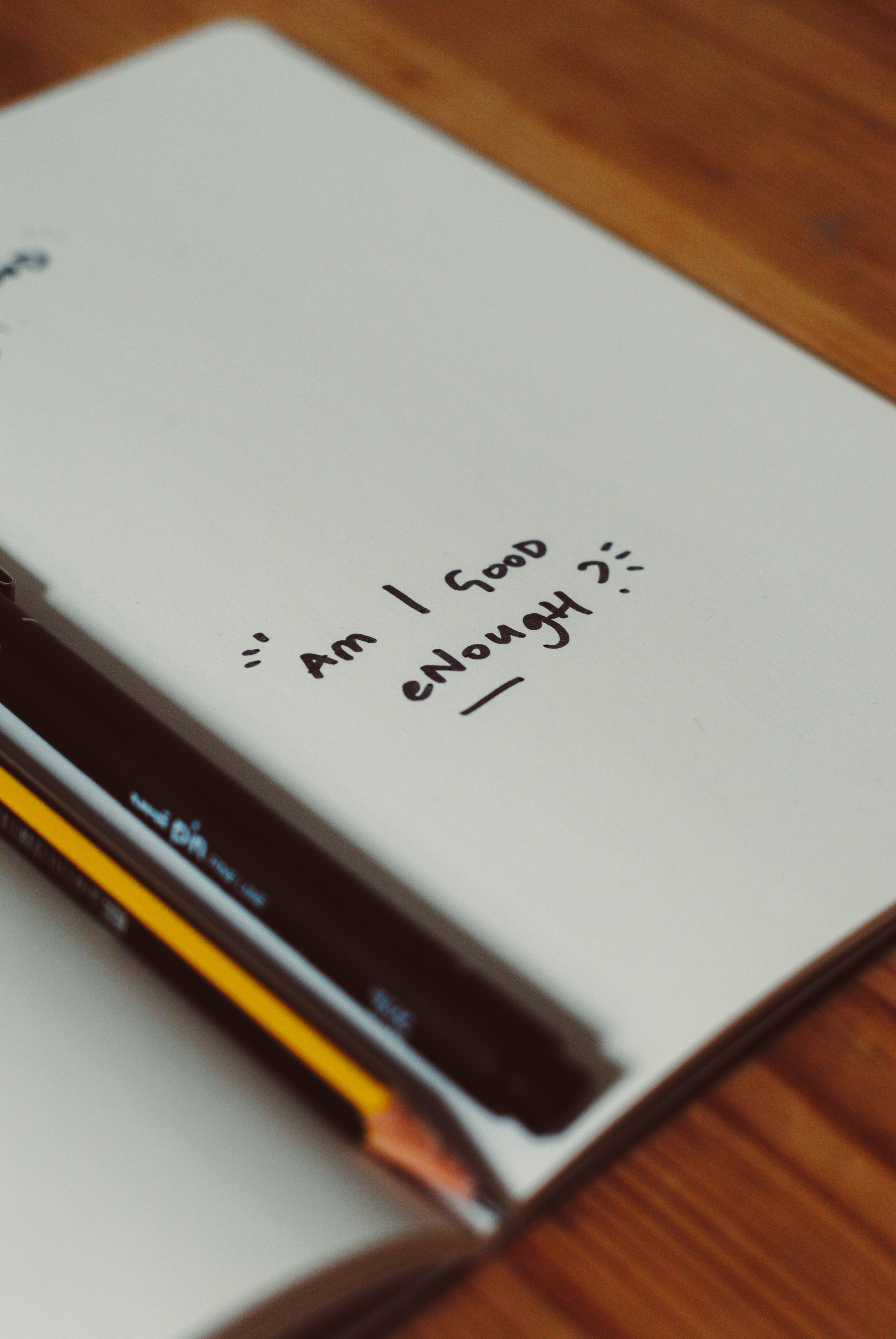

“Am I enough?” is a pervasive, if tacit, question in today’s college culture. Michelle Obama opens up about her relationship with the question in her new memoir Becoming, and Rachel Simmons — best-selling author and girls’ leadership specialist — addresses an iteration of it in the title of her recent book, Enough as She Is, which focuses on the “College Application Industrial Complex” and the pressures that young women face in a culture of “perfectionism 2.0.”

Equally, if contradictorily, pervasive is the rhetoric of resilience. Angela Duckworth’s notion of “grit,” or “passion and perseverance for long-term goals,” has sparked education professionals to ponder whether perseverance can be taught or tested, and Carol Dweck’s conceptions of fixed and growth mindsets have students, parents, and professors touting the values of process-based teaching and learning.

But genuine resilience suggests a more integrated approach towards acceptance (of oneself and one’s circumstances) than perseverance, and holds important power in one’s perceptions of self-worth. Harold Cohen, Ph.D., defines resilience as “how well a person can adapt to the circumstances in their life,” suggesting that resilience requires flexibility and change in the face of challenge, rather than the no-holds-barred, power-through-it approach inherent in definitions of grit — a virtue that is often found in what psychological researchers Niiya, Crocker & Bartmess call “overstrivers.”

College culture promotes overstriving, and I — guilty as charged — understand its call. On traditional campuses, students live, study, and socialize in communities of competition whose standards are set forth during the application process, long before young adults ever step foot on campus. It can therefore prove difficult to release those messages throughout one’s time in college — to let go of the feeling that one is in a boxing ring, under a spotlight, required to perform and outperform past record-setters.

However, the most common and ruthless opponent in these battles is usually oneself: one’s own perceptions of achievement and success, one’s own approaches to failure. If we examine the pressure that students feel to prove themselves, we might find that they — that we — are hustling to prove ourselves to ourselves, striving to beat our own personal bests on campus and beyond.

This is not to minimize or overlook the external factors that influence students’ self-perceptions or definitions of success. Outside influences and influencers sculpt students’ learning experiences in more ways than I can recount here. However, as long as students have what psychologists call “contingent self-worth,” their time in the boxing ring will never end, and its psychological implications can be devastating.

What is Contingent Self-Worth?

Contingent self-worth is a phenomenon in which self-esteem is a dependent variable, meaning that it is mediated and modulated by intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Niiya, Crocker & Bartmess study academic contingent self-worth, or senses of self-worth that are dependent on academic outcomes and achievements: GPA, test scores, graduate school acceptances, etc., while other researchers have honed in on appearance-based contingent self-worth (think weight, muscularity, and Snapchat filters); power-based contingent self-worth; and even the ways in which extrinsic contingent self-worth leads to greater materialism (a vulnerability that is targeted directly by marketing companies, thereby perpetuating mass-media messages that make us think and feel that we are not “enough”). Influencer culture, dominated by everyday people who are sponsored to project images of perfection in correlation with products or services, seemingly heightens this problem. As Simmons writes in her book, celebrities are no longer the primary (curated) images of success to which students are exposed. Instead, it is the peers and strangers that fill Instagram feeds to whom students compare and calibrate their lives.

In a study involving 128 college students enrolled in an introductory college psychology course, Niiya, Crocker & Bartmess discovered that students’ academic contingent self-worth was a malleable trait, meaning that teachers could scaffold the extent to which students floundered or rebounded after challenges. Through their words, researchers reveal, teachers have the power to influence the lens through which students perceive academic stress and success.

“Incremental Theories of Ability”

For teachers interested in boosting students’ senses of self-worth in the face of academic setbacks, Niiya, Crocker & Bartmess emphasize the importance of a classroom culture founded on incremental theories of ability, or a “learning orientation” centered around the belief that “improvement is possible.” This sentiment echoes a Dweckian growth mindset and, researchers confirm, is relatively easy to facilitate:

“Simply priming incremental theories of intelligence through a brief text buffered self-esteem from failure,” they write. “This finding suggests that shifting people’s focus from demonstrating their ability… to learning and improving… could be an effective intervention for vulnerable self-esteem and depression among people with highly contingent self-esteem.”

As Claude Steele found in his research about the ways in which stereotype threat influences academic performance in minority populations (see Whistling Vivaldi), the narratives that educators share prior to an assessment or performance-based task shape students’ outcomes and attitudes towards that task. “[O]ther approaches to achievement situations, such as having a goal of obtaining successful outcomes, outperforming other people, or validating one’s ability,” amplify academic contingent self-worth, and teachers who stress those values — by emphasizing assessment of competency, for example — unwittingly perpetuate contingent self-worth in students who are prone.

Taking Control

Realizing the risks of contingent self-worth in students, some colleges have taken action. In 2017, for example, Smith College — a private women’s liberal arts college in Northampton, Massachusetts — implemented a program called “Fail Well,” also spearheaded by Rachel Simmons, in which students and professors worked together to communally “destigmatize failure.” In their coverage of the initiative, the New York Times referenced a term created by professors at Stanford and Harvard: “failure deprived,” coined to describe an uptick in the number of students seemingly unable to cope with even the smallest setbacks.

In an era where millennials get the (grossly inaccurate, in my opinion) reputation as being a “snowflake generation,” it might feel too easy to buy into this idea of a coddled, cozy swath of young adults so guarded from challenge that they are unable to cope. After reviewing scholarship on contingent self-worth, however, it seems critical to inquire: Are college students really failure deprived, or is our culture of “perfectionism 2.0” the culprit behind the contingent senses of self-worth that consume college students, rendering challenges a reflection of fixed personal value rather than opportunities for growth? I contend that the fault is not on students’ shoulders, as is implied by the “failure deprived” title, but rather the institutions and influences that surround them.

The onus of self-worth is not solely on educators’ shoulders, however, and neither is the combatting of contingent self-worth contingent on others. If you are a student looking to cultivate a healthier sense of self-worth, here are several strategies to try:

Journal about what you’ve learned from past challenges

The reflective power of journaling is integral in processes of identity development, self-exploration, and the scaffolding of self-worth. To bring to the fore a “learning orientation,” take five or ten quiet minutes to write about three significant challenges you have lived through, how you endured those times, and what you learned from them. Calling to mind the knowledge that you now have, having made it to the other side of this difficult experience, will boost your ability to find meaning in future struggles.

Gain perspective by helping others

Third-person perspective taking, a foundation of empathy, is the ability to imagine another’s thoughts and feelings as if they are one’s own. One way to practice third-person perspective taking is through volunteering to help those who are struggling, whether tutoring a younger student in math or serving meals at a local food bank. Amid the flurry of college deadlines, schedule in an hour per week—or even per month—to pause your schedule and extend a hand to someone else. It might just boost your sense of self-worth, and another’s.

Make a list of attributes that are independent from success

Crack open the spine of the journal you grabbed in Step 1 and make a list of admirable attributes you possess that are independent from success. Are you compassionate, honest, sincere? Are you a good listener, a caring friend, or a loving sibling? Write down as many positive traits as you can think of (that are disconnected from mainstream notions of achievement), and refer back to this list when facing challenges that might lead to contingent self-worth in the future.

Write (and read aloud) your own pre-performance pep talk

Niiya, Crocker & Bartmess emphasize that teachers’ narratives influence students’ self-worth. However, you can conjure your own pre-performance pep-talks too. Write out a paragraph-length “success manifesto,” reminding yourself of the incremental theory of ability; the idea that time and practice lead to improvement; the lessons you have learned, and can learn, from failure; and the positive attributes that will endure despite the positive or negative outcome of any given task. Store this paragraph in a special place and read it aloud before heading off to a challenge: a big sports tournament, GRE exam, or other stress-inducing endeavor.

Subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

More on Mental Health on Campus:

What Campus Mental Health Centers Are Doing to Keep Up With Student Need

If You’re a Student Who’s Struggling With Mental Health, These 7 Tips Will Help

The Hidden Stress of RAs in the Student Mental Health Crisis