Early in the space age, we struggled to define our relationship to artificial satellites.

The first, Sputnik, launched late in 1957, surprised and scared us; its cheeky beep-beep-beep reminded us that there could be a weapon or a spy camera passing right over our heads. A month later, Sputnik II transported the first living creature into space; we mourned for Laika, its doomed canine passenger. Early in 1958, when Explorer 1 carried the first scientific instrument into orbit, a cosmic ray detector, satellites became our scientific partners, augmenting what we might learn, measure, or discover by using ground-based tools alone.

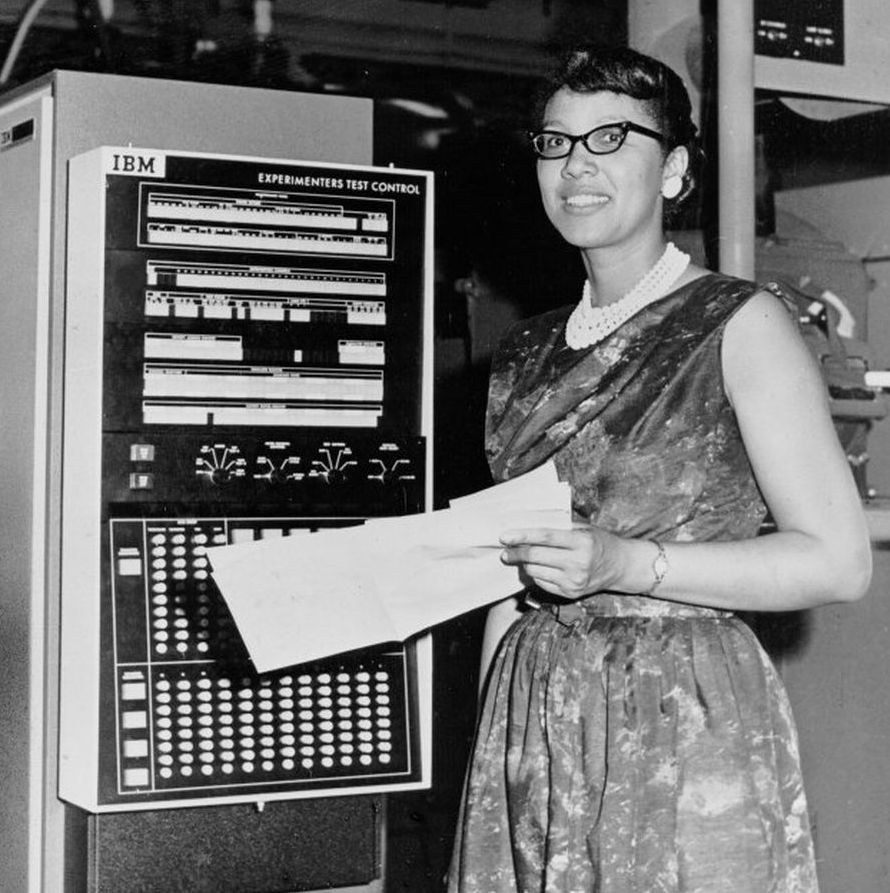

Echo, launched on August 12, 1960, was a simpleton of a satellite (actually a gigantic balloon, inflated once in orbit), covered with an ultra-thin layer of reflective Mylar. Its shiny surface allowed scientists and others (including President Eisenhower) to bounce signals from one place on Earth to another–the first step toward building the complex orbital communications network we all use today.

Thousands more satellites would follow (there are 2000 active Earth orbiters now). Rapid advancements in communications technologies, as demonstrated by Echo’s more sophisticated successors (including Telstar in 1962), rapidly eclipsed the “one-trick” capability of the passive Echo orbiter. And yet, Echo’s reflective skin contributed greatly its immediate and enduring glory; the Mylar covering was so shiny, the satellite could easily be seen making its way across the night sky. Anyone, anywhere on Earth, could be a part of the Echo experience. No tools or special knowledge were needed.

Echo was the first public, participatory event of the space age, perhaps the first step in popularizing space exploration in a fully inclusive way.

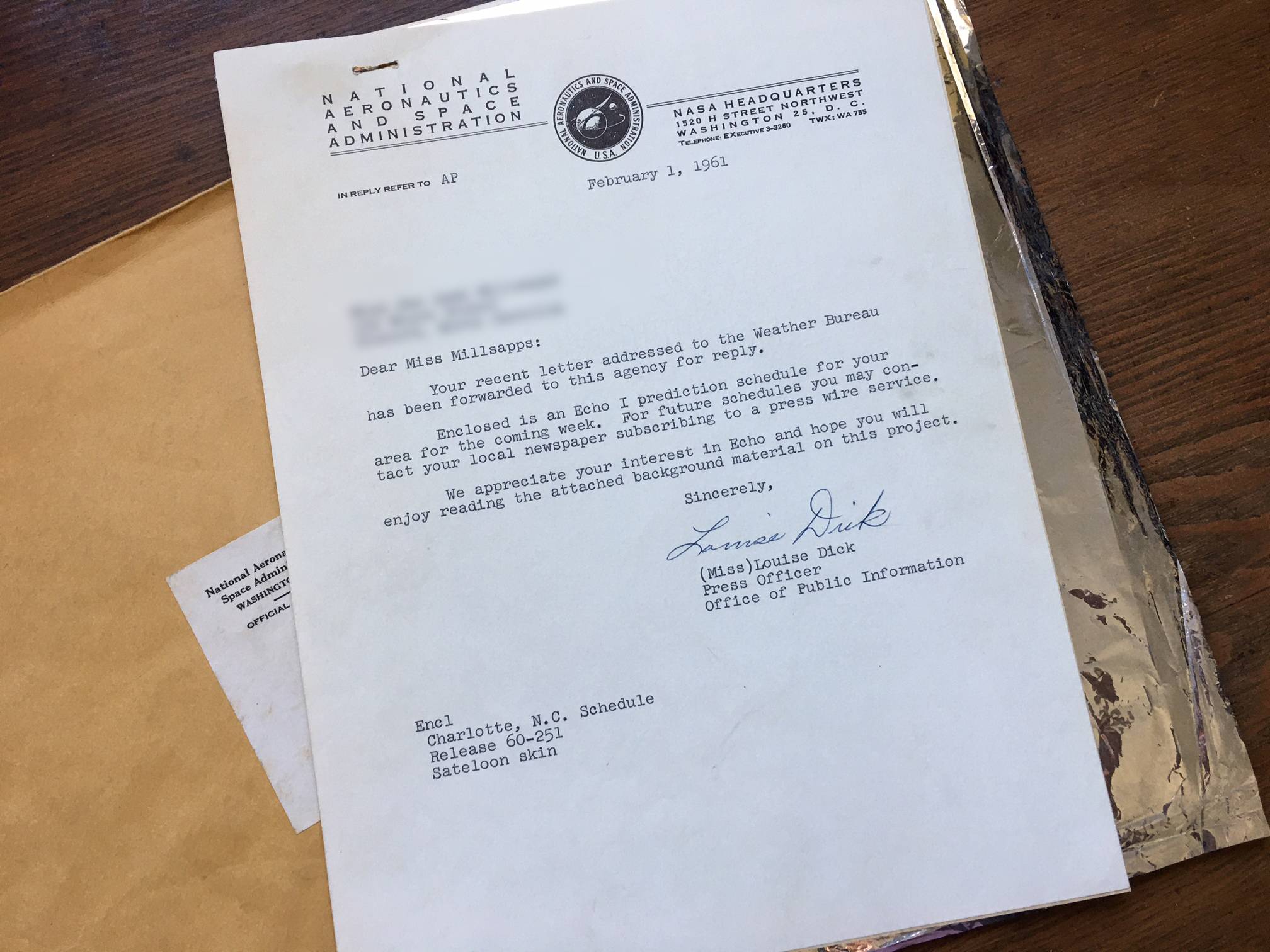

My family watched it nightly (I think the local newspaper published a viewing schedule). My little nerd self went a step farther: I sent letter to NASA, and got back a sheet of the Mylar used to cover satellite, plus an information packet, treasured artifacts of the early space age I’ve kept for 60 years.

Less than a year after Echo was launched, a few carefully selected humans joined the satellites we’d sent into space. Most of us could not see ourselves in these celebrated men, an exclusive community of spacefarers that would not reflect the diversity of humankind for many more decades. But Echo, who continued orbiting until 1968, reflected all of us. Stepping outside on those cloudless evenings in the early sixties, anyone who took a look could see himself or herself in space – mirrored there in the satellite’s shiny surface.

We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us. ― Marshall McLuhan

Jan Millsapps is a space age kid who still participates in space-themed activities, evidenced by her novels Screwed Pooch and Venus on Mars, and her award-wining documentary Madame Mars: Women and the Quest for Worlds Beyond. She serves as a volunteer mentor for the UNOOSA’s Space4Women initiative, and will be hosting an Oct. 5 virtual event for World Space Week on how women use satellites today.