“Why had Dad chosen that first spring break, in April of 1971, to start the process of filling me in on his history? Couldn’t he and Mom have somehow opened up earlier, averting all those years of shut-down? I got the answer during one of my talks with Dad when I was in college. With a wistful look in his eye, he said that when Sally and I were quite young, he’d been extremely worried about what to tell us about his bouts of psychosis and hospitalizations. Shouldn’t we at least know something, he wondered to his doctors, especially as we got older?

Yet Dr. Southwick, his main psychiatrist, quickly responded. “Never discuss mental illness with your children,” he told Dad; “any such knowledge will permanently destroy them.” Unconditionally and professionally ordered, the entire topic was off limits. Mom was part of the pact as well.

Talk about stigma! During the 1950s the psychiatric profession forbade family members from knowing about the very forms of illness under its care. Would an oncologist direct a patient never to divulge his or her cancer to family members, including children—or a cardiologist, heart disease? It’s unthinkable.

But mental illness was so shameful that banning all discussion was believed to be therapeutic. Our family’s role-playing was off and running, professionally sanctioned—even ordered.

This stance is, quite literally, mind numbing. Stigma is another kind of madness, the worst kind of all, far beyond mental illness itself. Enforced silence—motivated by shame and advocated until recently by the mental health profession—produces disastrous consequences for all involved. Of course, disclosure to one’s family, friends, or colleagues is always a matter of timing, judgment, and prudence, but we must fight the default assumption that opening up is disastrous.

Once I turned 18, perhaps Dad reasoned that I was no longer a child, so that any disclosure at that point wouldn’t go against the medical advice he’d received. Or maybe he was finding it impossible to pretend any longer. Given the one-way nature of our conversations, I never asked. But if I could reconfigure history, what might our family have said all those years ago about Dad’s condition?

I can’t really imagine, because of the magic act we tried to pull off every day. But saying almost anything might have taken away the sharp edge of blame, anger, and terror that were my barely acknowledged companions.

My colleague at Harvard Medical School, the noted child psychiatrist William Beardslee, has developed a form of family therapy for situations in which one or both parents has a major mood disorder, like depression or bipolar illness. Beyond the individual treatment needed by such parents, this therapy targets the huge tendency to hide what’s happening inside the family. In other words, it directly addresses silence and stigma.

During the program, the therapist encourages the parents—initially without the children present—to work to find clear language to capture the family’s experience. Understandably enough, most parents initially resist such disclosure: They’re too young to understand; wouldn’t it just hurt them? Why would we open up about such a shameful topic? Yet through prompting and coaching from the family therapist, the parents develop a narrative that their children will comprehend. Eventually the family convenes and the therapist guides the parents to talk about Mom’s absences, Dad’s anger, family drinking patterns, time off work, or whatever the particulars may be.

The goal is to prevent what too often happens, which is that the children blame themselves. In fact, when families experience problems but nothing is said, kids usually take on the blame by internalizing the conflict. This stance may appear puzzling, but at least the child maintains some control over the situation—and this perspective is probably better than believing the world to be a cruel, random place. Yet such responsibility clearly increases the child’s self-blame and guilt, enhancing later risk for depressed mood. With open discussion of the family’s realities, this process of internalization may be headed off at the pass.

Children in families receiving this form of family treatment, now called “Family Talk,” function better immediately afterward than children in more traditional family interventions. Even more, and intriguingly, their risk for developing mood disorders is substantially reduced up to four years later.

The implications are remarkable: Although part of the risk for mental illness is transmitted via genes, and strongly so for bipolar disorder, another part of intergenerational transmission is related to communication. Even in our biochemical age, breaking the silence is essential.”

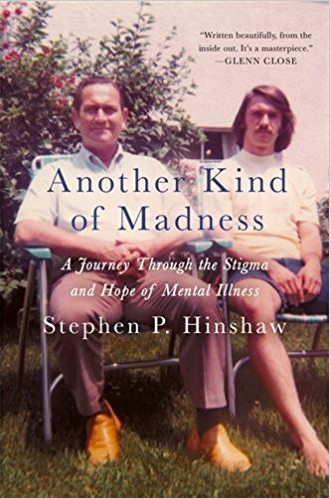

Excerpted from Another Kind of Madness: A Journey through the Stigma and Hope of Mental Illness by Stephen P. Hinshaw, Ph.D.