My dad died when I was twenty-four and in graduate school at the other end of the country. After my sister had told me the news, my mother soon called. She encouraged me not to come to the funeral. I was poor, she reminded me. She could not help me finance the travel to the funeral.

I was only too happy to take that guidance, using the expense as my excuse. I have deeply regretted that decision ever since.

___

Growing up, my family was highly avoidant about facing death. My parents came by this pattern in painful ways. My dad’s father had got up from the dining room table, walked into the kitchen, and never returned — dying on the floor of a heart attack and leaving my traumatized father with a lifelong source of fear and difficulty with loss.

My sweet, loving mother? The person who said “do not come”? I learned only after her death, from a long lost cousin found through a genetic website, that my mother’s mother had died of suicide (I’d secretly suspected that) and my poor mother blamed herself for her death. Ouch. No wonder.

My childhood makes so much more sense knowing those things. In an attempt to protect themselves from feelings of loss, both of my parents tended to wall off painful feelings in many different ways. And yet by avoiding loss, we lose contact with something else entirely.

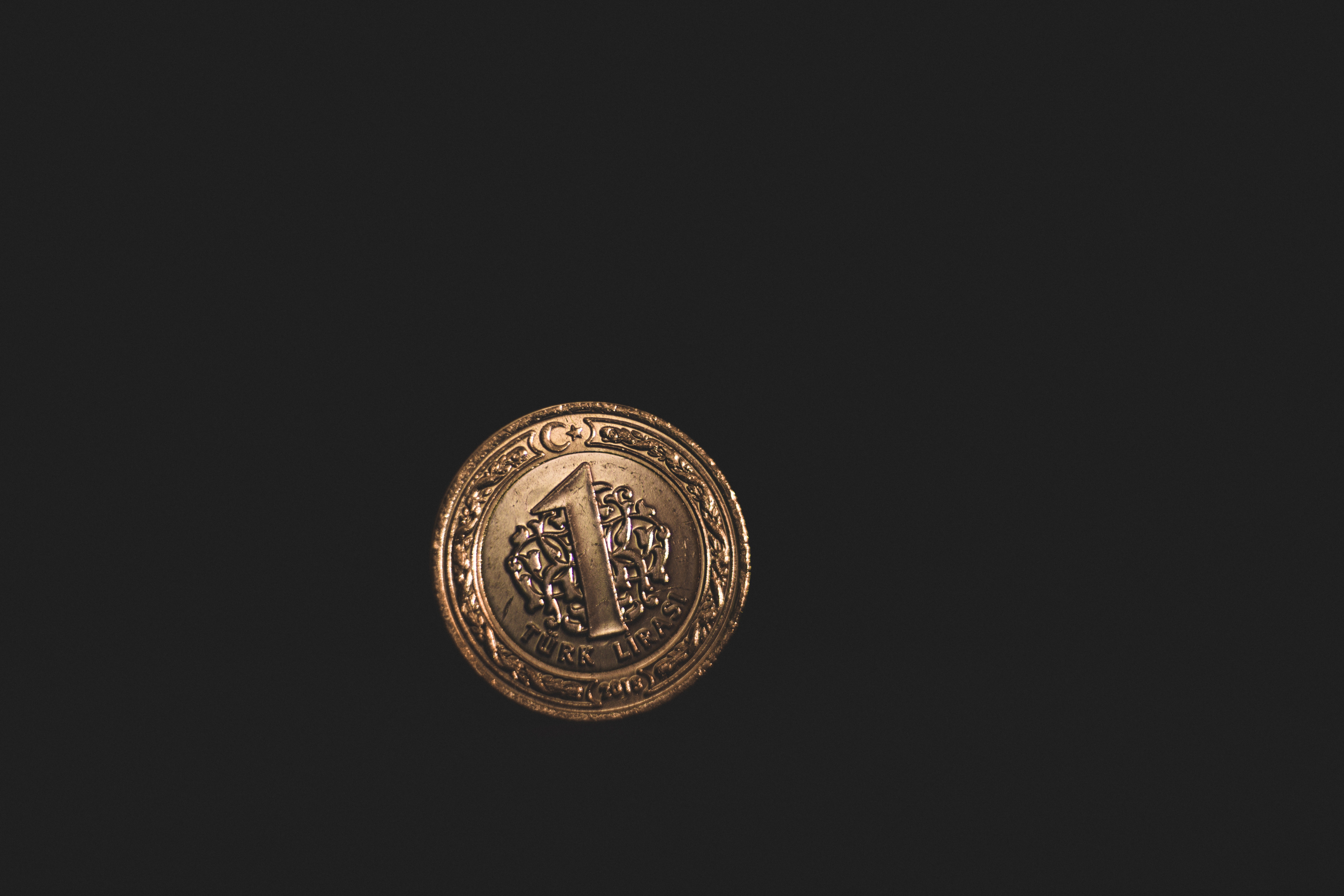

Because avoiding loss also means to avoid a part of ourselves that is loving. Loss and love are like two sides of the same coin. They are one thing – inevitably connected to each other. And if you can’t witness loss, it’s like love doesn’t matter.

As you go through life, you will experience loss in many shapes and forms: You will lose loved ones, relationships, future perspectives, important opportunities, property, security, and even parts of your identity when you change who you once were.

But by avoiding contact with the painful feelings of loss, you also limit your ability to express and experience love. The only way to shut yourself off from the pain of caring is to shut yourself off from caring in the first place. That is a lonely and empty place to be in. A recipe for depression. But the voice in your mind encourages it, saying “protect yourself”, “protect yourself” — when really it is actively harmful.

The more you open up to feelings of loss, the more you can connect to feelings of love. Your ability to feel one side of this coin shrinks and grows in relation to your ability to feel the other side. Personal loss is inevitable, but you have a choice how to respond to feelings of loss.

Poets tell us that willingness to feel loss scoops out a place in the human heart that can then contain love. We get not a drop more of love than we are willing to feel as loss.

I think the science of psychological flexibility suggests the same thing.

–––

A couple of years ago, I received a call from my sister, Suzanne. She told me my ninety-two-year-old mother’s pneumonia had taken a turn for the worse, and so I immediately got on a plane from Reno to Phoenix.

By the time I got to my mother’s bedside, she was no longer speaking or opening her eyes, but her head moved slightly when Suzanne said “Steven’s here.” I think she knew I was there. Surrounded by my sister and her grown children, I sat with my hand on my mother and watched over a period of hours as her breathing slowed and her body shut down. I sat and watched my mother die.

It was a precious moment. I was so thankful to be there and to honor her life and her love by feeling the pain of loss. Intensely sad, yes, but sacred.

You don’t eliminate loss. That’s not how it works. You open up to it because it’s how we know that love matters.