Prior to Covid-19, I mostly thought about strangers as warnings to my children. Around the time I first began teaching my daughter Izzy to not talk to strangers, we were standing in line at Panera. She was scrutinizing the people behind us so intensely that I was about to tell her to stop staring when she pointed and said, “Mommy, are those the strangers?”

“Well, those are strangers, but not the strangers.” I shot the couple a friendly smile to show I wasn’t one of those hyper-vigilant moms who’s mistaken fear for security. I’m wary in public, but I also want my children to know that the world is full of mostly good people.

In fact, strangers can sometimes bring certain comforts, like the ones who offer presence without the freight of intimacy. Take the nun I found in a rest stop on the Massachusetts Turnpike. I was on my way back from a trip to Smith College, and exhausted. It was damp with the threat of snow, but I was still sweaty from the adrenaline of speaking to a group of students about women’s equality at work. All I wanted was a McDonald’s cheeseburger, a guilty pleasure I justify only when traveling.

It wasn’t the kind of place I was expecting to find connection. Rest stops have lots of potential to attract the strangers. So when I collected my cheeseburger and fries, I spied a booth, and then directly across from it…a nun. She seemed at home there, relishing a Big Mac and large fries. I gave her a quick smile as I passed and she looked from me to her food with what felt like guilt. I fantasized that she escaped her convent once a week to come here and indulge in secrecy.

My last stop before leaving Smith had been to see Kathy McCartney, the president. She and I had talked about spirituality, the MeToo movement, and its impact on women. On my way out, she gave me one of her last bound copies of a speech she’d recently given. I tried to let her keep it, but she said, “No, no. Take it. You should have it.” I wanted to read it in the parking lot, but Kathy had let me use her parking spot and I felt like I’d been in it too long already.

In my booth, I pulled out her speech and read it while I ate my fries. A page into Kathy’s words I was crying. She wrote that suffering can soften us and open us to the world, and included a Mary Oliver poem that called darkness a gift. I don’t cry in public, but there I was wiping my eyes with rough McDonald’s napkins. The nun must have noticed because we were facing each other, but she kept her eyes down. She was either giving me space, or happy to have some of her own, but it felt like we understood each other.

Which was cool because I didn’t want to have to pull it together. I’d been on all day, trying to be a perfect female CEO. My tears were, in part, a release. When I was leaving, there was a shorter route to my car through the side door, but I walked past the nun’s table. I caught her eye and said, “Sometimes only McDonald’s will do.” Her red cheeks spread into a wide smile and she nodded. I imagined her watching to make sure I got back to my car safely.

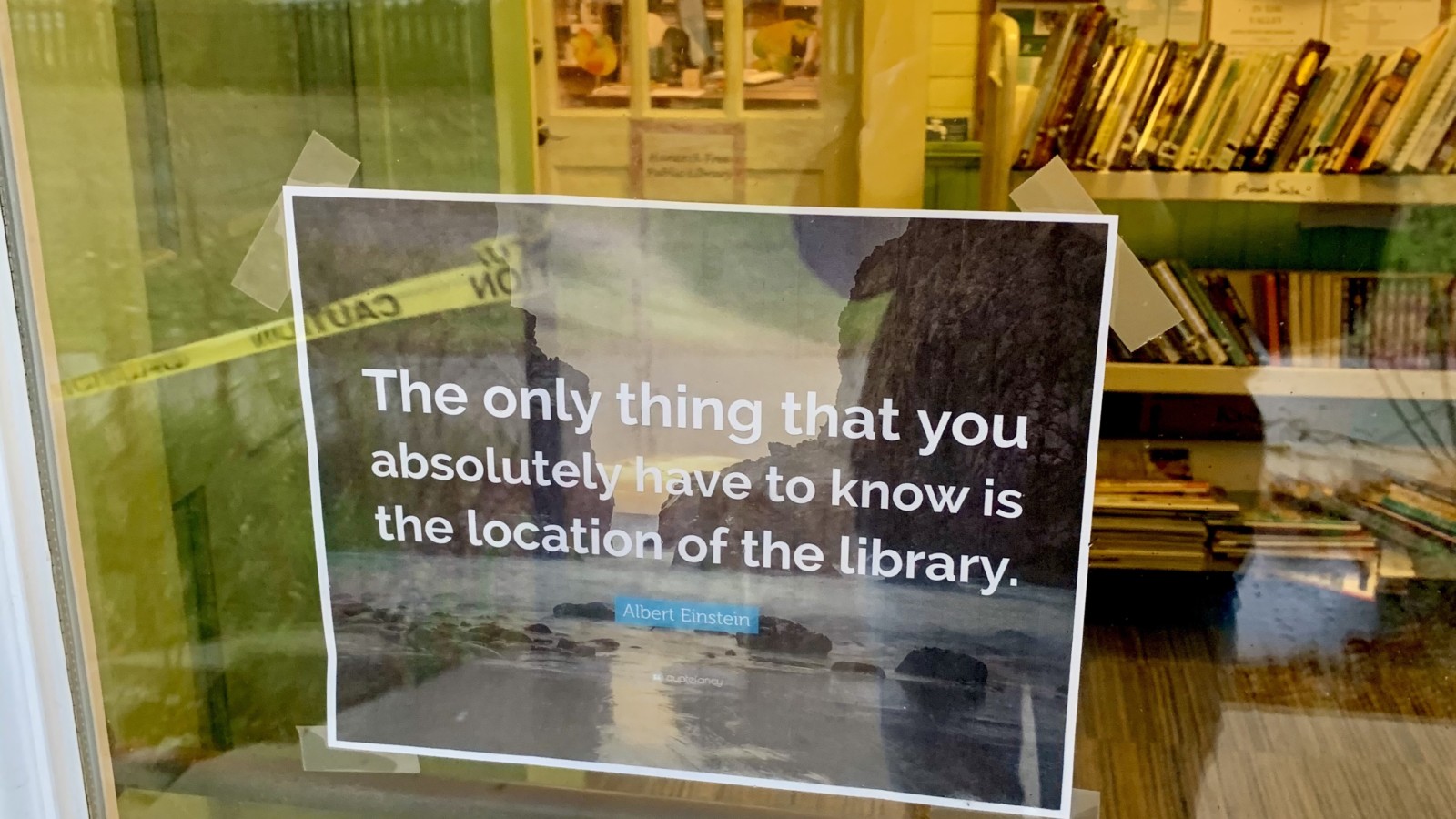

Another pre-pandemic encounter with a stranger provided even more than witnessing; some strangers can drop in on moments to stitch us back together. One Tuesday morning, I was returning some children’s books to my local public library on my way to work. The books were overdue, and I was about to be too. I was taking a 10 a.m. call from my car, wondering if I’d have a chance to use the restroom before a 10:30 meeting. Internally, I was complaining. Do I need to schedule bathroom breaks on my calendar? How does a library not open until 10 a.m.? What about people who have jobs?

An elderly man was also waiting, albeit much more patiently, and he introduced himself as Sheldon. We chatted for a few minutes until a man working at the library opened the door a crack, seemingly to loosen the latch so they could open, but then he turned back to go inside. Sheldon asked, “Can we go in now?” He was doing this for my sake.

The library employee wasn’t having it, “No! The library isn’t open yet! 10:00 a.m.!” He pulled the door closed and locked it again. It was 9:56. So why did he even do that? I fumed to myself.

Sheldon turned to me, “There are two kinds of people in the world, and he’s the other kind.” Now we were allies. I asked what he was doing at the library. In a neat bundle, he carried a stack of poems that he’d written on a typewriter over many years. Each morning, he came here to convert them into digital copies.

He told me he lived alone now, and read me one of his poems about love. Then he said, “You know, you can’t launch every campaign. Some people challenge the world, but all we can really do is take care of the people who are in front of us.”

This stranger, I thought, was sent. It was as though everything had been orchestrated so I could hear his message — the waiting, the rude man at the library, the poems. There may be fewer strangers than we think. During the pandemic’s isolation, I lost sight of this insight. But as massive vaccinations signal a hopeful end, I’ve realized something about the strangers. I want them back.