‘Scales’ was probably the film I most yearned to watch in Venice.

Ever since viewing Shahad Ameen’s Doha Film Institute supported ‘Eye & Mermaid’ at the Dubai International Film Festival four years ago, I knew this was a filmmaker I would forever more keep on my cinematic radar. And of course, she proved me right.

‘Scales’ just won the Verona Film Club Award for most innovative film in the Critics’ Week section where it premiered. Ameen proved that her unique vision and world outlook not only make for great entertainment but teach us something about the future of filmmaking.

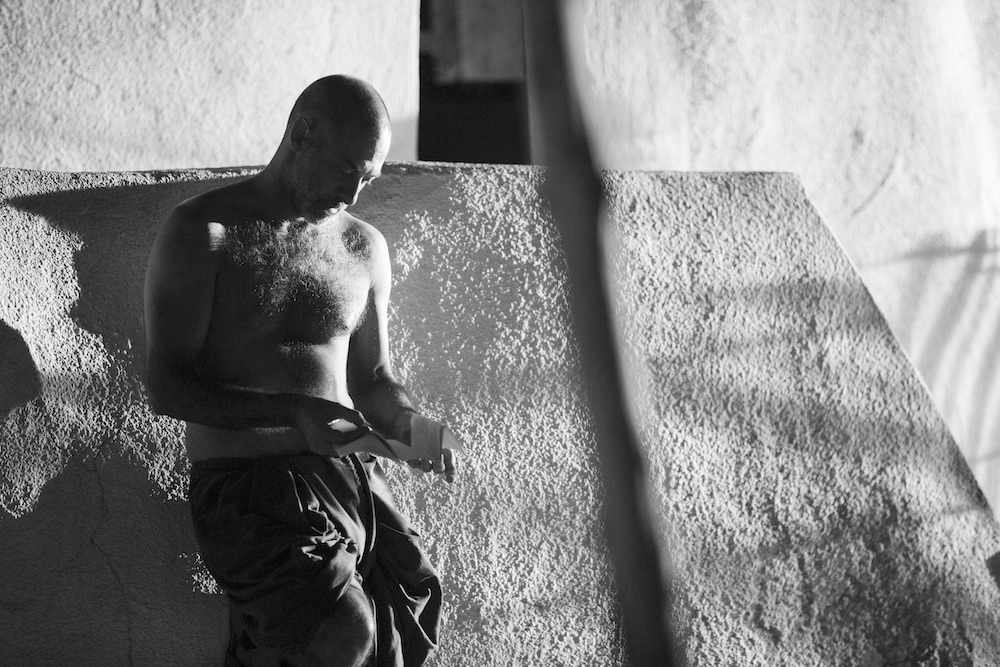

Shot by DoP João Ribeiro in stunning black and white, concise and precise, as well as a beautifully acted film — with a cast that includes Baseema Hajjar as Hayat, the protagonist and Palestinian wonder actor Ashraf Barhom as the antihero Amer — ‘Scales’ outdid my expectations. It is co-produced by ImageNation Abu Dhabi, with producers R. Paul Miller, Stephen Strachan and Rula Nasser, as well as executive produced by Mohamed Al-Daradji and Majid Al Ansari. In the project’s early days, ‘Scales’ also received a development grant from DFI which of course gives credo to cinema’s unifying power in this age of squabbles in the Gulf.

Giona A. Nazzaro, the General Delegate for Venice Critics’ Week, said the following about ‘Scales’: “I was aware of the project for a long time. I was also aware of the previous short Ameen had done [Eye & Mermaid]. Obviously there were great expectations but the film was even stronger and bigger than I expected. It was stronger and bigger in a very interesting way because it’s a film that does not show off. It’s a film about the craft itself of filmmaking, it’s about how you reshape the world with the tool of cinema and it’s one of the most interesting and challenging coming of age stories of the last years.”

That, and the fact that the film features an Arab mermaid, at a time when we are having trouble even seeing an African American mermaid, makes it all perfectly groundbreaking.

To sit across from Ameen, we are from different generations and varied cultural backgrounds, I kept thinking how in awe I am at this woman, who has come to the realization that it’s great to be a woman this early in life. It took me many more years, and I still struggle with it at times. To me Ameen is this incredible representation of what a Saudi modern woman truly is, and yet she is also so international in many ways. Ultimately, I do believe she does the work of a 100 ambassadors for her country, Saudi Arabia.

Following is my interview with the wondrous Shahad Ameen, from the garden of the Hotel Quattro Fontane on the Lido, in Venice.

‘Eye & Mermaid’ is where the idea came from and yet it’s all so different. But it still explores this theme of women and freedom. How did that short film become ‘Scales’?

Shahad Ameen: I remember as soon as I had finished ‘Eye & Mermaid’, I’d already begun writing ‘Scales’. What I wanted to do in the script was make sure I didn’t repeat myself. So I needed to tell another story, in that same mermaid world, with the same concept in a sense. If I was going to repeat myself, why do it? I already told my story in ‘Eye & Mermaid’.

A lot of people were thinking this was the feature length version of your short film…

Ameen: No no. I would have never done that. ‘Eye & Mermaid’ for me stands alone. I never meant it to be a two-parter. They are both different films and I wanted to explore different stories. I’m not the kind of director or human being to keep repeating myself. I would get bored.

In ‘Eye & Mermaid’ I explored the effect that has on girls, but I did not continue the story of the journey of the kid. That’s what I was missing. In a way in ‘Eye & Mermaid’ the father was the antagonist, and I hate that word, but he was the one doing the horrible things. In ‘Scales’ I wanted to explore the relationship of girls with themselves, when they grow up in societies treated like second-class citizens, treated like someone who is different from those around them. I wanted to see what that does to a girl.

In a way, I wanted to explore what that did to me. Through ‘Scales’.

And you have a very good father figure, like Hayat in the film, you have that kind of relationship with your father.

Ameen: For sure. I have a father who is definitely a feminist in his own right. I have an older father, he is in his 80s now, and he grew up — imagine being in Medina where he’s from, being that man back then. When we were born, I have six sisters, four brothers, and he was a big supporter of the girls. He was hard on the boys but with the girls he really gave the full support. He was against certain things in life, he was against wearing the hijab, he did not support that idea whatsoever. For a man who grew up in his generation he was definitely ahead of his time, in the way he raised us.

He put education and our own self worth ahead of everything in life. I wanted to show that in the story. I did not want men to be the antagonists. I wanted them all to be victims of circumstance, because at the end of the day, that’s what we all are. But I also hate victim’s stories so I made Hayat discover her own way to avoid being a victim.

I love that you placed your story in this dystopian near future where human beings have to survive because they have exploited everything. How is that important to your story and to you as a human being?

Ameen: I kept repeating a poem to my aunt and in it, it says we keep repeating our same mistakes. It’s as if we’ve lived for four hundred years and are still in the same circle that does not change. It stays the same, unless someone stands up and says “hold on, I think there is something more, I think we need to change!”

I think you saw that in ‘Scales’. It’s funny, when you look at it it’s very obvious that they need to change. It’s very obvious for an outsider. But when you are inside a culture, where you are inside in the reality, it’s very hard to change.

We still do it today, we argue about climate change, as if it’s a legend. It’s obvious, it’s here.

Ameen: They are stuck, as we are. It’s a universal story of them being stuck in this cycle that goes on and on, as we may be, until someone comes along and says “do I want to be like my parents and my grandparents?” Or do I want to respect what they had and build on that. That’s the true reality of the film, is where Hayat is the one who breaks the cycle. She unknowingly perhaps journeys through breaking the cycle. For me that was very important.

You’ve chosen an actress who represents you physically, so how much of Hayat is actually you, Shahad? And how much are you the other characters too?

Ameen: She’s definitely much prettier and much more charming! Around the time when we were shooting, by the second week of shooting, by the end when I would watch the frame, I would think “is Baseema acting like me or am I acting like her?” I felt that either she was having my reactions in life or I am having hers. Maybe when I saw her, I thought she had an understanding like me of her worth as a woman. She had an understanding because she grew up in a society that told her you’re not good enough and yet she decided to become an actress at age six. She’s from my hometown [Jeddah]. When we shot ‘Layla’s Window’ my short film, she was seven and then for ‘Eye & Mermaid’ she was ten, and for ‘Scales’ she was twelve.

But I think I’m the other characters in the film. A lot of people when I was writing the script everyone used to confuse our names, Hayat and Shahad when giving me notes. And I love that one of my mentors, when watching the film said to me, “I love that Baseema made it her own.” I was much more tomboyish, much more feisty, much louder. But I built a world, I was very confident and a lot of people weren’t with me, a silent world. I needed a city where people are sacrificing their own daughters to eat them! It’s the reality of how disposable women are in the Middle East, and how disposable our problem is. It’s not big enough, because it’s not a male problem — from their perspective. Because men don’t feel our problem, and our emotions and pain, then it’s not a world-wide problem. This is my chance to talk about it.

In the West you may not be as aware as a woman, because you still have privileges but we are treated as lesser beings, as women.

It’s less subtle in the Middle East but it’s definitely a world-wide problem!

Ameen: Yes, you’re right. I was talking to an Italian friend, and she was like “but we don’t need anything else, we have everything as women,” and I said “no, no, you think you have everything but if you give anyone for a second the opportunity to take your rights away, why would they give them to you?” No one is going to fight for you.

How do you feel when people say, “well, you’re not really a proper Saudi woman” or are surprised by your outspokenness and strength?

Ameen: I get upset. I remember I did an interview once with a Danish channel and they were like “but you’re not really Saudi?” When I was traveling in New York people would say, “but you’re like us, you’re not really Saudi.” And I’m like no, no sorry, I’m Arabic and I’m very proud of my Arabic heritage. It’s what made me who I am. I’m very proud of being Saudi and I’m even proud of the dis-privileges, if that is even a word, that being Saudi has given me. Because it really showed me who I am. Every person who went through being discriminated against and not receiving privileges, that’s a good thing!

This is what the globalized community has given us. A world where we are aware as Saudis of the rights we didn’t have and yet we are very Westernized, in the way that we studied abroad and we understand different cultures. And what we stand for the most is acceptance.