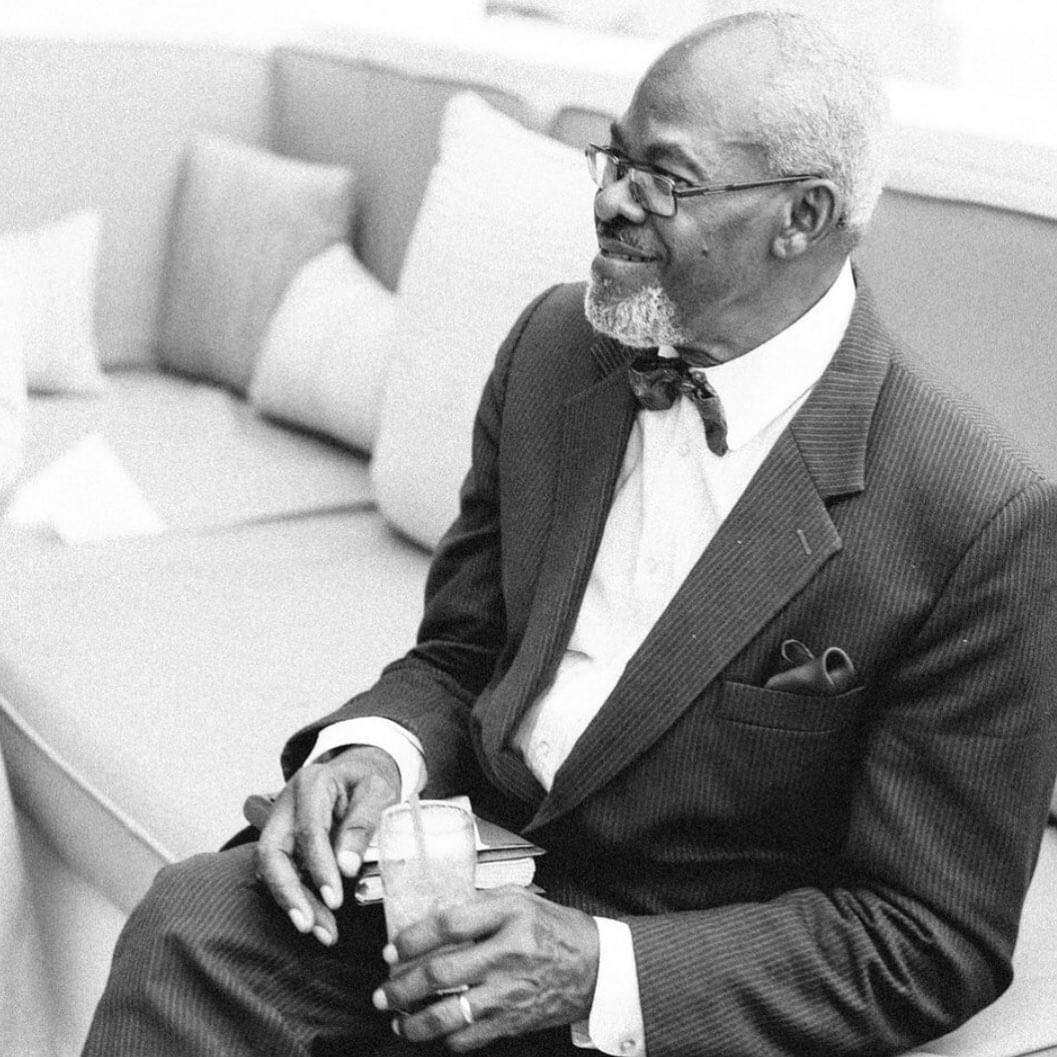

“You’re as good as any, and better than many.” For as long as I can recall, my father’s favorite saying has been my personal mantra. As a Black girl growing up in a white-dominated world, being equal to or better than others was a heady way to imagine myself, but it was an idea that my father earnestly wanted me to believe. I did and it turned out to be my greatest gift, inoculating me from the virus of white supremacy and the otherwise crushing weight of living in a racist world.

Learning to Love Myself

Dad was a scholar of racial ideology and dynamics, so knowing that he had a brown-skinned, woolly-haired daughter to raise, he embarked on a mission of counter indoctrination for my malleable brain. My days began with effusive, heartfelt compliments about my appearance – statements like, “Good morning, pretty girl!”, or “How is my beautiful daughter doing today?” His words were cringeworthy to me, especially in my teenage years when the boys I dated heard him saying them too. That all changed one day when I listened to a famous Black actress discussing how unattractive she felt growing up because of how different she looked from the images of beauty that surrounded her. It was only then that I realized that my father’s efforts resulted in me never once thinking that I was ugly.

Of course, there were times that I subscribed to some of the beauty standards that were societally pervasive yet alien to my most natural self. For a handful of years I used chemicals to flatten my hair’s pattern and before returning to wearing my tresses the way they grow out of my head, I even dabbled with a version of the late 20th century half-straightened, oily mess of a hairdo known as the “Jheri curl”. I eventually abandoned those styles but beyond my hair, I had other Black features with which to contend, yet my father’s standard of equal to or better than was the one that stuck in my mind. It was not a standard characterized by definitions – it never mentioned my kinky coils, my ample round bottom, or my rich cocoa skin. The standard was simply me; it was whatever constituted who I am. I couldn’t define it but I knew that I embodied it. That knowing made me decide that I was just fine; that whatever my nose looked like must be attractive since it was the only nose that had ever sat squarely on my face – the same face that my father constantly reminded me was beautiful.

Maximizing my Mind

Despite contradictory gender and racial beliefs in society, Dad signaled to me that my intellect was at least as remarkable as anyone else’s, regardless of their relative status in the world. When I would tell my father things that I had learned, his mouth would open wide in amazement and his eyes would bulge with approving wonder and surprise. My heart fluttered each time he did this, and an irrepressible grin would form across my lips. I adopted the feeling that I had something important to say and that the world needed to hear it, so I began broadcasting my knowledge to anyone who would listen. At five, I approached strangers to tell them that “psychology is the study of the mind”. By six, I was rattling off the spellings of multisyllabic words for my teachers and my parents’ friends.

It was all very obnoxious. It was also what has led me to value my voice and raise it loudly in every space I occupy. It spurred in me a lifetime of protest and community building and notoriety and revolt. It made me believe that elite institutions and rarefied rooms of corporate power were as much my domain as our family’s own backyard. It freed me to weigh my goals and achievements against my own ideals, rather than sizing them up against a bar of white achievement, which mental health experts now know to be a debilitating practice for people of color to employ.

A lot is currently being written about anti-racism and the plight of Black parents who are tasked with raising children in a racist world. The prevailing advice tells parents to be intentional about discussing race with children. They should. It recommends ensuring that children have outlets for their own activism to feel empowered and hopeful. This is an integral part of my parenting framework SHAPE, which melds the best research available with real-life experiences to guide the parenting journey.

Yet for all that I have learned in my decades as a child development specialist and as a mother who birthed and co-parented three African American young men, one thing is clear: an overdose of affirmation and acceptance is the most effective vaccine a parent can administer to their child. My father’s framing of me as “equal to or better than” has been the basis of my self-love, self-care, and unrelenting commitment to change. On this and every Father’s Day, I am grateful.