I tell people I got into public relations because I wanted to be a writer. The catalog for Syracuse’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications listed writing as a core PR skill, and I was too practical to major in something more creative. However, I think the real reason is it gave me an opportunity to practice my niceness. In my family, we lived by the axiom, “If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.”

In high school, I honed these skills working at a gift shop that sold collectibles. The radio was tuned to “light and easy favorites” and the glass cases were lined with cherubic figurines and ceramic animal statues. Our top-sellers were Dept. 56 Christmas villages. Some customers put additions onto their houses to display their collections.

Every fall, Dept. 56 released limited edition pieces, which were gone in a day. Customers who came away empty-handed blamed us, of course, some yelling to speak with the owner. To manage them, I played a game with myself. No matter what the customer said, I wouldn’t raise my voice, or even appear upset. When I didn’t have anything nice to say, I smiled and got Linda. She had a way of standing up for the truth without escalating things.

Not much had changed when I founded my company, Inkhouse, except there was no Linda to go and get. I was Linda. I was 31, full of hard work, and terrified that I was in over my head. My mantras were “Fake it until we make it” and “We’re in the image business.” To pair with the H&M dress people often mistook for a Diane von Furstenberg wrap, I bought Jimmy Choo heels. I coifed myself into an entrepreneur for my mostly male clients. I was going for respect and likability. “Clients don’t fire friends, they fire vendors.” Another early mantra.

We had three clients and I’d arranged for the CEO of one to be on the cover of a Time supplement. He was on the other side of the world at the scheduled interview time when the reporter called me. “Your client isn’t answering,” he said. “I’m available now, or tomorrow, but my deadline is tight.” I called the front desk at the hotel where my client was staying and convinced them to knock on his door.

When my client came to the phone, he yelled, “What do you think you’re doing?! I could’ve been with a girl! When I get back to Boston I’m going to fire everyone!” He carried on for what felt like a long time while I coached myself to sit there and take it. In my part of the world, the sun was setting while I drove to a networking event, my “fake it until I make it” clothes drenched in sweat.

When he finished, I took a deep breath and said, “It sounds like there is a lot to talk about when you get back, but the reporter is on the other line. Do you want to talk to Time?” He did.

I wanted to fire this client, but I couldn’t afford to, and I also didn’t have the guts to. He apologized a few weeks later and I felt vindicated. I’d won the gift shop game again. It never occurred to me that I could hold him accountable for bad behavior.

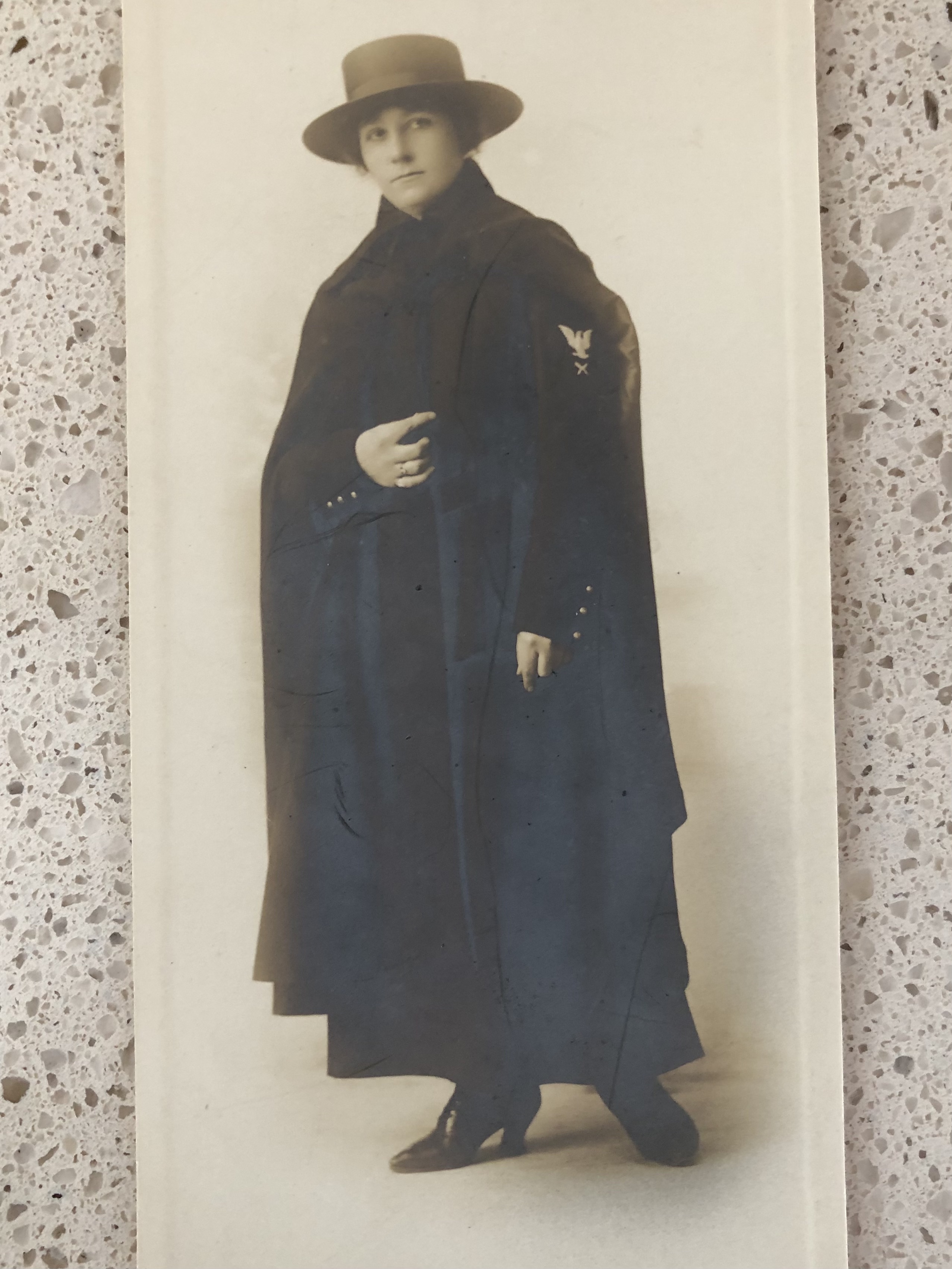

Wilda Coleman in her WWI Navy uniform.

And so, you may ask, do I come from a long line of people pleasers? Surprisingly, no. In my parents’ attic, there is a photo of my great-great-aunt Wilda Coleman wearing a military uniform. She’s confident with her shoulders back while she stares straight into the camera. During World War I, Wilda got into the Navy on a technical error. The 1916 Naval Reserve Act stated that “any U.S. citizen” could join. Wilda was one of 11,000 women, called Yeomen (F) or “Yeomannettes,” to enlist. Yeomen (F) received the same pay as men who shared their rank, which was almost unheard of in civilian life. These Yeomannettes hoped their service would convince President Woodrow Wilson to give women the vote.

What did those Navy men say to Wilda when she showed up? When she spoke about her time there to the Columbus Dispatch on July 31, 1963, the year the Equal Pay Act was passed, she didn’t mention it. She said she was only like “any young folks out for excitement.” I don’t know what she was out for, but she saved that uniform for almost 50 years. It was obviously a symbol of great pride.

Her sister-in-law, my great-great-grandmother Martha Hudiburg, was born in 1891. Women were just gaining legal status then — a fact which continually blows my mind. In America, until the 1880s we operated under the coverture laws we adopted from England. A married woman, a “feme covert,” was “dependent like an underage child or a slave, and could not own property in her own name or control her own earnings, except under very specific circumstances.”

Martha though didn’t seem to care about laws or tradition. She divorced her husband, went on to live with multiple men and never married again. She also ran a bookie ring from her home. When my father stayed with her as a kid, he said she was always on the phone saying numbers. But he also talks about how Martha stayed with them for a month each summer. She lay in bed giggling with his sisters late into the night telling them stories. He texted me, “She was the life of the party.”

I recently came into possession of Martha’s bed. It’s beaten up, but my daughter Izzy and I put it together in our driveway before packing it off for restoration. I ran my hands down its posts and sat on the wood slats hoping to absorb a little of what it knows about giving the middle finger to the way things are.

Martha and Hilda were trailblazers. I should have been able to assume their mantle, given that I grew up in the 1980s when things supposedly were more equal. That equality was a cover though. You can read it in the manuals with advice for women in the workplace published at the time. “The Ambitious Woman’s Guide to a Successful Career” from 1982contains a section header called “Is Your Personality a Plus?” The answer is no. There are also sections called “How You Sound” (you should be more feminine so you don’t threaten the men) and “Sex with the Boss” (it may “prove detrimental”). These were manuals on how to play my gift shop game: shut up and try not to piss anyone off.

The first time I lost that game on a large scale, Inkhouse had about 15 employees. We’d won our largest account and the CEO was terrible. He sent emails on Sundays about non-emergencies that said, “Call me immediately.” He yelled at one of our best employees who’d spent the day at his office managing media interviews. She came back in tears, and I knew we had to choose her over the client, to choose culture as our business model.

Today, Inkhouse has grown to four offices and 130 people. Gone are the 80’s maxims of faking it until you make it. Now, our agency values line the entryway at Inkhouse’s headquarters in a pretty series of fonts that still bear bold lines to get the point across. “We aren’t order takers.” “We use good judgment.” “We are accountable.”…“We are kind.” Kind, not nice.

I’ve been imagining Wilda as she put on her 1918 Navy uniform for her 1963 newspaper photo. And Martha sleeping in that bed for her whole life, reinforcing the base with metal rails at one point. I think of these items as tuning forks for nonconformist souls. If I follow their vibrations, maybe I’ll keep my grandchildren up late giggling while I tell them stories about breaking the rules.