As I wrote my memoir, Small Fry, I tried to hear what I might describe as snippets of a barely-audible internal conversation. Two parts of me that look nothing like me, but that nonetheless are me, whisper to each other, and if I could get still enough to hear them, I could write. Listening like that, I didn’t feel like myself at all — I disappeared.

When I got a text or checked the news on my phone, the conversation vanished. I would snap back to my old self the way a sea anemone retracts when touched, all of its arms gone. I was Lisa on the earth again, 5’2”, with skin and clothing and opinions and nervous jokes. I’d lose the delicate voices for at least a day, maybe a week.

Still, when my writing lagged, I’d reach for my phone. I couldn’t help it! I’d read news and get a whoosh of satisfaction. In fact, I’d get more satisfaction reading an article than I might get from a whole day of writing. If I tried to write with the phone beside me, I’d check it more and more often. The life inside the phone swelled, my own project shrunk. The phone helped me skip boredom and uncertainty but those two states, however unappealing, are the only two roads I’ve found to my work.

Somewhere in the middle of the many years it took me to write the book, I moved to Brooklyn. A few days later, I carried my phone to a nearby café that served sandwiches and ice cream and played Ella Fitzgerald all day.

“Can I leave my phone here, with you?” I asked.

I happened to be dating again at the time, and also I liked my phone, and I liked my friends, and texts, and emails—so I didn’t want to rid myself of a phone entirely—but I also couldn’t have it nearby. I needed intermittence, but I didn’t have the discipline for it. If I hid the phone in my house, I’d just go find it again.

“I’m trying to write a book,” I said. “I find the phone distracting.” (I had a landline for emergencies.) I worried they’d think I was nuts.

“Yes!” said the young woman behind the counter. “I get it.”

We fell into a pattern. I’d drop off my phone at the café, they’d keep it in a folder below the cash register, and I’d retrieve it in a few days or a week. The feeling after dropping it off was lonely, but also wonderful: I had my whole day, my whole life, to myself. Why not write? Time expanded.

I’ve since moved away from that house and that café, but a poet friend recently introduced me to a food addictions lockbox he’d found for sale online. It has a timer on the top that can be set from a few minutes to a few weeks. My phone fits inside. When I need to focus, that’s what I use now.

In retrospect, maybe I wrote the book, in part, to expand time. My childhood was over, but it went too quickly. I wasn’t ready to become an adult until I’d lived inside it more, until I’d wrestled with it and it had blessed me. In the book, I wrote about one day when my father took me to play hooky—he’d taunted me with this new word, hooky, for a few weeks beforehand, and then, on the appointed day, he skipped work and I skipped school and we went to San Francisco. I’d assumed we’d play it again now that I knew what it was, but we never did. In writing the book, without my phone to distract me, I got to play it again. I got to spend time with my parents when they were both young until, finally, it felt like enough.

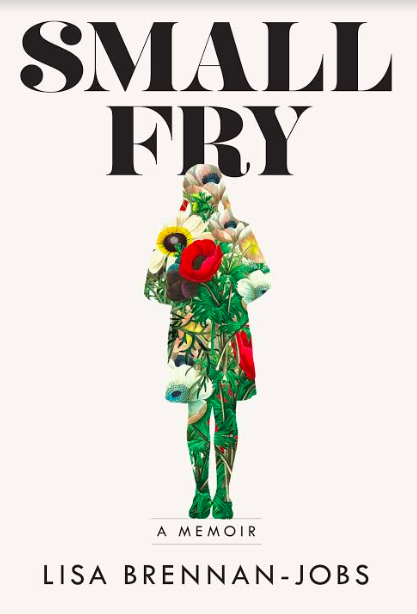

Small Fry is available now.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.