Silos and Turf Wars

“This is America. We don’t share land here.” —John Dutton, Yellowstone (Paramount Network)

We all likely have seen “chained in the cave thinking and performing,” where this thinking and behavior becomes the thinking of trapped organizations.

Where disaster strikes, when the separation of different types of workers become victims of a grain entrapment incident, where the grain (the crop that has sustained their community possibly for generations) turns into quicksand inside 50-foot silos.

Shareholders, leadership, family, neighbors, and first responders, must put aside their differences to save their organizations from drowning.

When groups function within silos, that is more like cloistered walls of a cave with half-seen images on walls, taken as real in the shadows—these groups adopt false beliefs and make bad decisions.

These shadows are the illusory forms of obscured realities; at best, the symptoms instead of the causes.

Where information sharing (mindshare) between teams becomes scarce as information becomes a power in the silo game in the organization.

Unfortunately, this obsession with data and technique often becomes an addiction, Edwin H. Friedman said, that turns professionals into data junkies, and their information into data junkyards.

In this climate and an ensuing emerging culture, initially stated problems are not ‘the real” problems.

Blind spots and preconscious problems repressed by shadowy symptoms complicate organizational functioning and polarize climate and culture, leading to a cover your ass (CYA) or Trust your Neighbor but Brand your Stock mentality.

Treating the shadowy illusions as reality erroneously normalizes the abnormal (it’s still abnormal!). This kind of thinking is a sure way for executives to break trust with those that depend on them.

This style of thinking and the subtle nuances of its human dynamics trap workers, where disaster often strikes. Where workers suffer at the hands of leaders or managers who are playing “territorial games.”

A form of business play or sport in which activities focuses on protective behaviors to preserve leaders or managers organizational ‘territory’—the power or resources they have, that they are not willing to share with others.

Where “a turf conscious manager can grind genius into gruel.”

Creative spirits, motivated enthusiasts, and innovative drivers, Annette Simmons, says, in her book, Territorial Games: understanding and ending turf wars at work, become casualties of organizational turf wars.

We lose too many valuable resources, she claims, to the “friendly fire” of corporate turf wars.

Wars in which the fight is over currency: information is power, relationships, and authority (like command-and-control versus agile).

An organization (and even a farm), Salvador Minuchin, said, is a lot like a family having problems around a recent transition.

It is easier to help them, he claimed, than a family that has blocked adaptive negotiations over a long period.

“To confront a person with their own shadow,” Carl Jung said, “is to show them their own light.”

The critical takeaway here is that managing change (the subtle nuances of human dynamics) is not simplified; unrealistic behavior changes for the benefit of quick consumption that is easy, fast, or linear.

Nor is it faddish acronymic models, methodologies, templates, or toolsets, ad nauseam—reducing strategies, analyses, reports, or emails to a set of jargon-laced bullet points or “faddish infographics.”

Where accuracy and detail (nuances of human dynamics) are being pushed aside for the sake of a marketing segmentation plot, questionable sales pitches (change management licensing solutions, ad nauseam), as ways to fool the gullible.

A final critical takeaway is that change management (which, regrettably it has become) should not be like project management.

Change management is not submissive to project management; neither should project management be passive to change management.

Neither is change management timelines, the same as those for project management.

Managing change (or even change management), timelines, go well beyond project management—project management does not talk back, change management does. Logic is often slow. Fear is not.

Tunnel Vision

People see what they want to see and hear what they want to hear.

Unhealthy events happen when we passively monitor conditions without a need to respond.

We simplify the world to fit the structure of our prior notions—disregard evidence that disconfirms to this structure.

The relationship between tunnel vision, situation awareness (including assessment), and task performance challenge the complexity of handling multiple, interacting tasks, more often than a single, isolated one.

Tunnel vision like silos are trapping; once they snare us.

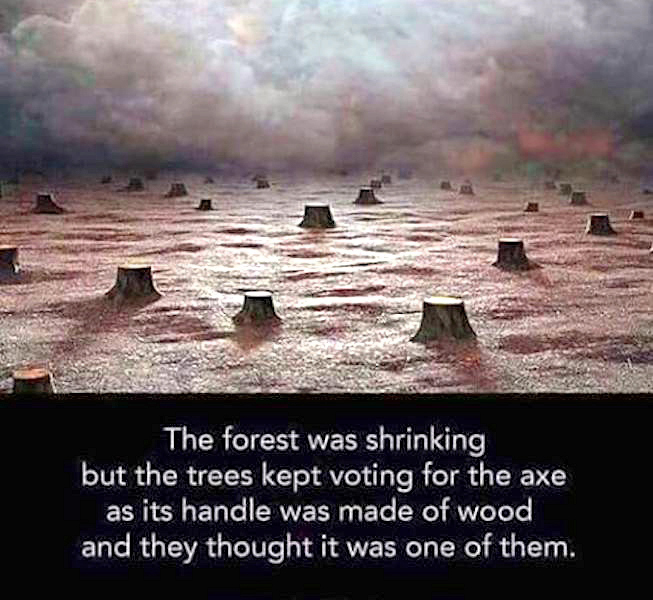

It becomes hard to set ourselves free from being stuck. Like the trees in the forest (in the picture above), we do not see genuinely what the ax is nor what it can do to us.

Everything, then, becomes our fault (learned-helplessness; an external locus of control versus an internal-locus-of-control).

Tunnel vision limits our common sense and perception. We see what’s in front of us, and not what we genuinely need to see.

Tunnel vision makes us blind to the opportunities around us. Instead of making progress, we remain stuck.

This vision creates illusionary views that partition or screen out early warning signals to us.

We miss these alerts because our attention is elsewhere.

Our passion nor our determination to work free from tunnel vision, as it is in silo-busting, is not enough to get us unstuck. We are working harder, not smarter.

We must shift our perspective. Doing so is how we break free of normalizing the abnormal (it’s still abnormal!); how we discover new solutions.

When we are not looking at the big picture of our reality, our emotional bandwidth begins to waste away.

Most of these reasons boil down to anxiety, fear, and stress.

“No thanks, I’ll stay here in my tunnel vision, or silo, where it feels safe.” Where I am holding tight, even repressing, further normalizing the abnormal (it’s still abnormal!).

Part of our fear of change is dealing with the unknown. This Japanese proverb frames this challenge well.

“Fear is only as deep as the mind allows.”

Engaging your workforce in transparency—facts and prospects for the future, make the unknown, known, and likewise, less frightening.

We cannot lead anyone, if we do not know, or see, precisely what we are going towards.

“We cannot lead our teams,” Max Heiliger argues, “to worship a torch because we think it is the sun.”

The ability to lead through change is an organization’s most valuable asset and leader’s most significant competency when they can do so.

It will determine which organizations can see and lead in the dark, and break free of chained in the cave thinking—those that will thrive, and those that will die.

“A narrow street is only as wide as the person that walks down it.” —Anthony Hincks

The Threat of Tribalism

They are badges of identity, he adds, not thought, and in a way, make thinking unnecessary—

“because they do it for you, and may punish you if you try to do it for yourself. To get along without a tribe makes you a fool. To give an inch to the other tribe makes you a sucker.”

I see this thinking and behavior in my consulting work in managing change with leaders, their line managers, and workers, who recognize their organizations as divided and compartmentalized.

Their immediate coworkers, and their department or function, as ‘special,’ alienating workers from other “tribes.” Regrettably, the very ones they must rely on to get things done.

The after-action-review, and lessons learned, remind me of what Rudyard Kipling once said in his interview, with Arthur Gordon, “Six Hours with Rudyard Kipling,” in The Kipling Journal.

“The individual has always had to struggle to keep from being overwhelmed by the tribe. To be your own man is a hard business. If you try it, you’ll be lonely often, and sometimes frightened. But no price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself.”

Nowhere are we seeing this more evident than now, during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Tribalism has been an inherent part of the human history.

Fear is a robust tool that can blur humans’ logic and change their behavior.

This logic and behavior affect consciously (and unconsciously) the way we think (processes) and act.

These processes bind leaders, managers, and workers into groups that allow them to make distinctions between “us” (members of the group) and “them” (outsiders).

Lilliana Mason, a political scientist, describes the psychology experiments, in her new book, Uncivil Agreement, that proves this behavior.

Where the common good means nothing and winning is everything—Which is the logic of American politics today.

The gambler’s money is like a river. Flowing one way. Our way …

Senator, you have never driven a road, walked a trail, or skied a mountain in Montana that didn’t belong to my people first.

This nation won’t give it back? So be it.

We’ll buy it back. With their money.

—Thomas Rainwater, Yellowstone (Paramount Network)