My writing partner, Stuart, would caution against author crushes. Should I tell him that I named my new electric car Joan Didion? This thought fluttered briefly the first time a notification flashed on my phone: “Charging of Joan completed.”

Why would someone name their car after an author? Well, if you’ve ever had to rely on books to help you survive life, you get it. I always chose irreverent and courageous female authors who left guides for that survival behind. In fact, I loved books before I loved writing.

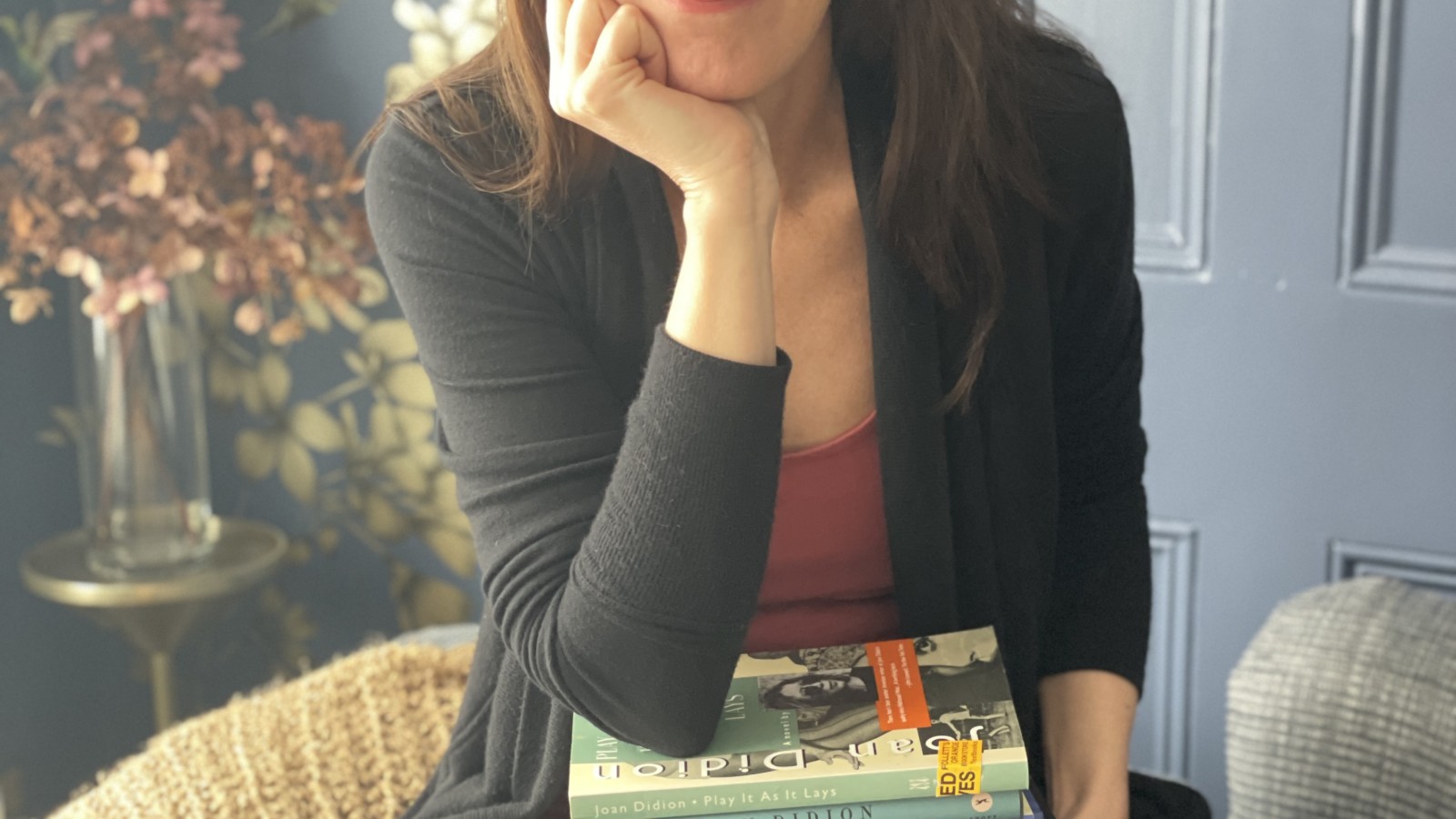

My crush on Didion began in college when I read “Play It As It Lays.” I still have the used copy I bought from Follett’s Orange Bookstore in Syracuse, New York for $6.75. Back then I didn’t write in my books so I don’t have a key to my favorite parts. But I remember the feeling when I finished: she was showing me how to stand inside my own darkness while still being able to take a look around. I wanted that.

When I began typing my own words, I wanted to write beautiful sentences. They’re how most of my author crushes begin. He looks shaken by this request, but still I monster on about it. Jenny Offill carving a moment in “Department of Speculation.” On and on she’ll go, the way she does when she thinks she doesn’t understand something and she’s scared, and she’s taking refuge in scorn and hypercriticality. A single sentence in Vivian Gornick’s memoir, “Fierce Attachments,” tells us everything we need to know about her mother.

Time is the school in which we learn. That’s Didion in “The Year of Magical Thinking,” her memoir about her husband’s death. She possessed the power to go through grief while witnessing it, which is how we make things make sense. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all. Didion again, in that book that made my crush run amok. I wanted to write and live like Joan.

When I read Didion back through time, I also wanted to be her in 1968. In “The White Album,” she published her own psychiatric report. She’d gone in for vertigo and nausea, but was kept there because of her “fundamentally pessimistic, fatalistic and depressive view of the world around her.” After a page-long reprint of her fragile mental health, Didion wrote, “By way of comment I offer only that an attack of vertigo and nausea does now seem to be an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.” Her packing list that year included 2 leotards, a mohair throw, cigarettes, bourbon and a typewriter.

Didion lives deep, lets herself off the hook, and never assumes she knows everything. I hoped reading her words would work like osmosis, but that’s not how writing or life go down well. The shift from reader to writer asked me to type my own way into living.

These days I read in between writing projects, but rarely during them. Didion’s new volume of essays, “Let Me Tell You What I Mean,” just arrived and I haven’t opened it yet. In advance of its release Time asked her what it meant to be the voice of her generation. Didion: “I don’t have the slightest idea.” I fell for her all over again, for a single line that is both humble and arrogant. I aspire to pull that kind of thing off. It’s okay to have stuff we love; it reflects the parts of ourselves that we’re working to grow into. And it helps us create our own stuff we love.

*This post originally appeared on the Book Architecture website.