When death is imminent or when it occurs, family members gather to connect and console one another in ceremonies and home visitations. In the Irish culture of my mother’s ancestors, this time is described as the “thin time,” the time when the veil between the worlds is lifted, and important truths and long kept secrets are often revealed.

As my son Kenneth lay in a hospital bed in our living room, now transformed into the dying room, relatives gather on the sun porch. I overhear their discussion of my younger brother, Kenneth who I named my son after. They spoke of his disappearance, and the recovery of his body by hunters nearly two years after he had disappeared. Eavesdropping from the other room I learned details and facts I’d never heard anyone speak of.

To Whom Do We Belong and Who Belongs To Us

Searching photographs after my sister’s recent death, and in preparation for her memorial I find an image of my sister’s first love, a handsome dark-skinned man I never got to meet. Our logical, usually fair-minded father’s unanticipated racism would not allow her to bring him into our house. I treasure the images I find of his and my sister’s beautiful daughter, given up for adoption at birth, partly to spare all of them the pain of family estrangement. One of the happiest day in my sister’s life was when her daughter, then grown, found her. They talked for 8 hours non-stop on the phone to “meet one another and catch up.” Lynn found us around the time of my father’s funeral and though she has declined our invitations to continue a connection since those first couple of years, we’re all grateful that we got to meet her and the mother who raised her when she joined her daughter in attending my daughter’s funeral.

To Whom Do We Belong and Who Belongs To Us

My husband had always known that his father, the youngest member of a “his, hers, and ours” family structure, carried much unhappiness because some of his close relatives refused any communication after his parents died. The estrangement lasted the rest of his life, keeping his children from knowing many of their relatives, or having any clear idea of what caused this family riff.

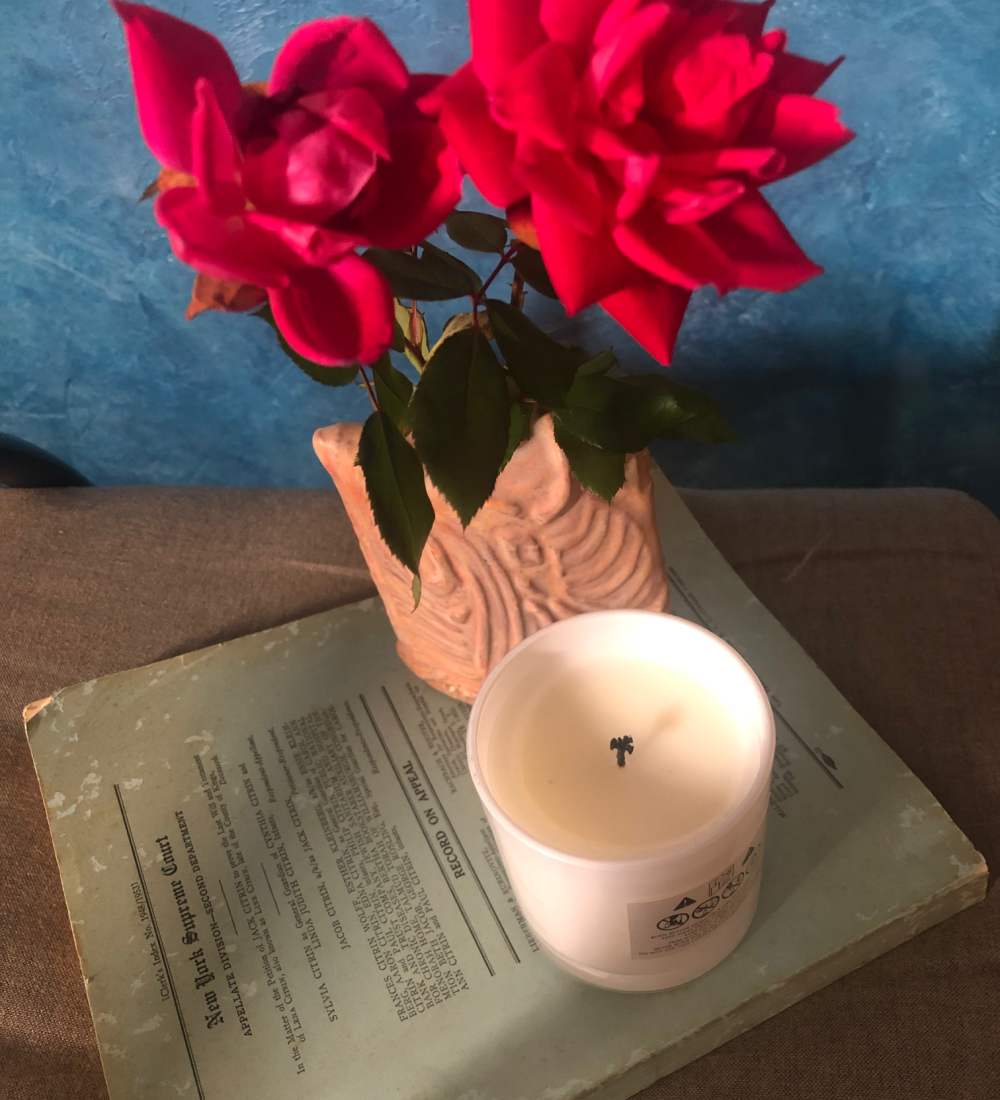

After Rich’s mother died, I was given the job of cleaning out her closet as we prepared to put her condo on the market. In the recesses of her closet, behind the shoes and the hanging, less frequently worn formal clothes, I found a dusty 200-page blue book. It was a transcript of a law case tried before the New York Supreme Court where family members and their heirs challenged the will of Richard’s grandmother which contained dispersion of funds from the family business. Richard and his brothers had been told there was such a court battle around the time Rich was born and that its outcome changed the laws of the State of New York regarding inheritance. Here were all the details–who said what in response to what questions under oath. There were 13 attorneys listed on the cover of the transcript which supported what Rich and his brothers had been told that most of the money had gone to the lawyers when the matter was finally settled. Reading this document, we could now see why family relationships did not survive the damage these proceedings caused.

To Whom Do We Belong and Who Belongs To Us

When my husband and I, after 14 years of marriage went through a divorce in Nebraska in 1975, I was a family therapist. It was with great sorrow that I had to admit that, though I had helped many client couples repair their relationships, I could not do that for my own family. Since my husband was unwilling to involve a counselor or mediator to help us resolve our differences, I knew I couldn’t play all the roles necessary to the mediation process; the objective third party, the wife, the mother, all at the same time.

My work with families had shown me the risk to our three children and ourselves if we pursued an adversarial process through the courts – a win for either side is a lose-lose for both. I got my husband to agree, that since we couldn’t make a good marriage, we could dedicate ourselves to making a good divorce. We worked out the terms ahead of time and hired a single lawyer. We appeared in court, only to be sent away. “I am not convinced that everything has been done to save this marriage,” the judge said. “This couple have three children and are asking for joint custody. They are represented by one lawyer and are planning to hold property in common. I am sending them to court ordered family mediation,” he said as he tapped his gavel on the podium.

Though there were few processes to support us as we transformed our family structure into a now common two household arrangement, it worked out well, especially for our children that we remained partners as parents. When I remarried my second husband joined the parenting team, often referring to my children’s bio-dad as his “husband-in-law.”

Estrangement from a family member is one of the most painful life experiences according to Karl Pellemer, author of the book, Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them, yet this type of loss has not been on most people’s radar until relatively recently. From his 10-year research on the issue in his Cornell Reconciliation Project Pellemer estimates that more than 65 million people suffer such riffs. Another author Kylie Agllias in her book, Family Estrangement: A Matter of Perspective looks at these losses that feel like a death through the lens of Attachment Theory, Bowen Family Systems Theory and Grief and Loss theories. “Whilst data suggests that around 1 in 12 people are estranged from at least one family member this topic is rarely discussed or researched.

It does help to know that we are not alone if an estrangement happens in our families. Like many other kinds of loss, removing the stigma allows us to support one another and compare notes on ways to heal it.