We who grieve are exiled in our society. Exiled by the turning away of a face so that they do not witness my agony. Exiled by the silence left as friends and family drift away. Exiled by the lack of recognition of this universal experience. Soon enough we sit in solitary confinement feeling as if no one else has ever felt what we feel. — Stephanie Ericsson

My husband, Marty, died of a sudden illness at age 39. A virus disguised itself as a cardiac cell and lured his white blood cells into feeding on his own heart, cell by cell, until the once powerful muscle was rendered useless. The virus that caused his illness strikes people of any age, randomly and insidiously.

Five months after Marty died, my friend Sadie phoned me. I took a deep breath and squeezed a sofa pillow to my chest as I talked with her.

Sadie and her husband Sam had been couple-friends of ours before Marty got sick. They were stalwart supporters during Marty’s illness, but our relationship had recently become strained in a way that I couldn’t identify.

She asked how I was doing. Haltingly, I told her that I was still struggling.

“Still?” she sighed. We sat in awkward silence.

Finally she said, “I’d always heard it was common for a widow’s friends to eventually stop calling after her husband’s death, and I always thought that was terrible. But now I understand.”

“Excuse me?” I heard myself say in a small, distant voice.

“Yeah,” she said, “it’s uncomfortable for me to be around you because you’re still in so much pain. Marty’s death makes me realize that what happened to you could happen to me and I can’t stand to think about it.”

More awkward silence.

Then, “I just want to be honest. Maybe we could just get together and go see a movie. The distraction would probably be good for you.”

Somehow I extricated myself from the excruciating conversation and hung up. I slumped in speechless disbelief as her words seeped into my pores.

Sadie was honest. But at what cost? In the midst of my traumatic loss, she abandoned me…

Because she was uncomfortable.

Anguished and forsaken, I screamed at the silent phone, “YOU’RE uncomfortable?! Try waking up in my empty bed every morning!”

***

I know Sadie had the best of intentions. She didn’t mean to hurt me, and she really wanted to help.

Unfortunately, we live in a culture that espouses positive thinking for every circumstance and solution-focused answers to every problem, so most people have no idea how to respond to a friend or loved one who’s going through something that cannot be fixed.

Situations like these leave us reeling:

- my husband’s sudden and random death when I was 30 years old and the mother of a still-nursing infant;

- my friend, a vibrant artist/father in the prime of his life who became debilitated by inoperable cancer;

- the daughter of one of my friends, a virgin who was brutally date-raped at age 17;

- one of my psychotherapy clients, a mother whose only child died of cancer at age 15; and

- another client, a mother whose only child developed a ravaging mental illness during her college years that pushed her to the brink of homelessness.

Bereavement, terminal illness, unspeakable violence, mental illness — these are only a handful of irrevocable life events that can yield indescribable suffering and grief in normal, everyday lives. There is simply no “making it better” when someone has sustained these kinds of life traumas.

The awful truth is that such agony can only be endured, not cured. This kind of pain is inconsolable.

In our culture, when we encounter a situation like this where we can’t fix the problem, we have no idea what to do to help. So we’re awkward and inadvertently hurtful, like Sadie. Or we don’t want to end up embarrassing ourselves by saying the wrong thing, so we say nothing.

On top of that, most information out there about how to help grieving loved ones consists of practical lists of tasks you can do or gifts you can give. Those lists are better than nothing, but they don’t do anything to quell the underlying fear and clumsiness you feel. So even when you offer a casserole or show up for a house-cleaning, you’re still left to approach your friend with stilted discomfort.

As a widow and a therapist who’s studied and helped with grief for 26 years, I’m going to offer you different way.

I’ll explain why you feel inept in the face of grief or trauma, and why our culture’s standard approaches to helping with grief don’t work. With that foundation of understanding, I’ll give you some gentle guidelines that will help you reach out to your friend with empathy and shared vulnerability… in order to offer care that truly helps.

Social Brains, Wired for Caring, Inadvertently Drive Callous Behavior

The stronger the love, the more the pain. Love itself is pain, you might say — the pain of being truly alive. — Joseph Campbell

Whether you want to face it or not, it’s inevitable that you or someone you love will eventually encounter some form of inconsolable suffering.

Social reactions to this kind of anguish are varied, but most of the time when someone is experiencing raw, irrevocable grief, almost everyone is uncomfortable around them, like Sadie was around me. No one knows what to do or what to say. Even my fellow psychotherapists are frequently stymied when it comes to effectively helping people with these kinds of losses.

Why is this so? If wrenching grief is ubiquitous to the experience of being human, why do most people react with such intense discomfort?

Your human brain is wired to be socially connected. An integral part of that social connection is a biological caregiving reflex: When you detect distress, especially in people you deeply care about, a kind of mirror-image distress occurs in you. That is, your loved one’s pain makes you feel viscerally upset in a way that draws you to attend to their pain and to try to assuage it. This reaction is normal, and it can generate healthy care and concern. (See John Bowlby, Jaak Panksepp, and Mario Mikulincer/Gail Goodman.)

However, when someone you care about experiences an irrevocable loss or trauma, you’re faced with a loved one’s distress and grief that cannot be soothed. The only thing that will truly comfort them is to bring the dead person back to life, to make the cancer or mental illness go away, to undo the rape.

The absolute truth is that you are powerless to change the conditions that are generating their pain, so you are powerless to comfort them. Therefore you as a caregiver feel utterly helpless at the very moment your biology is demanding that you render aid. (See Ossefort-Russell in Porges.)

When your caregiving reflex is hindered in this way, the natural order of things is thrown into chaos, and psychic distress occurs — for you! The need to help is so basic to you as a biological creature that the distress of helplessness, if left unconscious, can be overwhelming and can cause you to strongly defend against it.

Unfortunately, unconscious involuntary self-protection against caregiver helplessness is exactly what twists well-intentioned help into a mockery of soothing. Your mind builds a firewall of illusions that keep the burning reality of the randomness of life, your ultimate lack of control, and the inconsolability of grief and suffering from scorching you.

When your searing biological gridlock also occurs within our always-on-the-upswing culture that treats any kind of pain or vulnerability with contempt, it’s no wonder you have no training for how to truly help grieving or traumatized friends who are swamped by unbearable emotions.

You are most likely similar to Sadie, unconsciously hunkered down in your bunker of illusory safety, banishing the truth of immutable pain from your mind, clinging to the idea that there’s something you can do to make the other person get over their pain (so that you can stop feeling so bad).

So you blunder about with awkwardness when you face a griever. You thrash around saying and doing things you think are helpful, but which are in reality quite hurtful since the hidden underlying purpose of your actions is to alleviate your own anxiety.

Common Caregiver Missteps to Avoid

When dominant narratives become so deeply embedded in a society, even those whom they oppress end up internalizing them. — Ursula K. LeGuin

So that you can learn to do something different, let’s look at 6 common, misinformed caregiver attempts at help . These stem from the thwarted caregiver instinct, so they ultimately end up being isolating and hurtful to grievers:

1) You offer solutions or advice

You advise hope. You make suggestions for activities that will make the person feel better. You point out positive aspects of the situation. You express certainty that your friend will be okay, maybe even stronger than ever before. You tell your friend you’re worried about her — maybe if she knows she’s making you upset she’ll take your advice and get better.

“Don’t isolate.” “Be sure you do your grief work.” “Crying it out is good.” “You should distract yourself so you don’t cry so much.” “You need to get out more.” “You should stop doing so much.” “Volunteer work will help you focus less on your pain.”

Truth: Solutions and advice are reflexive, tone-deaf ways of trying to “fix” the problem of distress and grief. As I said above, there is no fixing this problem. Most of the time, especially in early grief, the very suggestion that your friend might ever feel better feels like an affront. It’s easy for you to look in from the outside and think you know what needs to be done, but there’s no way you can understand what it’s like to be inside the body of the person who’s lost everything. If you’ve been through something similar, you may have a better idea of what it’s like than the average bear, but no two people experience loss in the exact same way.

2) You offer reassurance in the form of clichéd platitudes

You have no idea what to say, so you parrot generalized statements you’ve heard from others, or trite sayings that convey your own beliefs.

“He’s in a better place.” “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” “She wouldn’t want you to cry.” “Time heals all wounds.” “At least he’s not in pain any more.” “God doesn’t give you more than you can handle.” “It could be worse.”

Truth: Platitudes such as these come across as uncaring and even insulting. There is nothing about any of these statements that speaks to the present experience of your friend’s devastation. They suggest certainty and sense at a time when your friend’s world has exploded and absolutely nothing is certain and nothing makes sense. These stale sayings subtly or not-so-subtly minimize or invalidate the pain your friend is feeling, and imply that he should buck up and not feel so bad.

3) You avoid mentioning the loss, the dead loved one, or the painful situation

You avoid the subject because you don’t want to make a mistake, or you don’t want to upset your friend.

Truth: Your friend is already upset. Not mentioning a loss or a terrible event leaves her alone with her feelings. Your silence tells her that her distress is unwelcome in your presence.

4) You point out that “negative” emotions are bad for health, so your friend should focus on “recovery” and “resilience”

This one is a special case of advice (see #1). You’ve fallen prey to our societal belief that painful feelings are evidence of illness that needs to be cured, that we should all focus on the positive all the time, and that we should “bounce back” quickly when adversity strikes.

Truth: Sadness, grief, anger, distress, disappointment, and other painful feelings are normal, healthy responses to difficult life events. It’s only when painful feelings are disallowed that they fester and become distorted and cause problems. Devastating life events permanently change us, and they take time to integrate into a life. Telling a friend who’s deeply grieving that he’s hurting himself with his pain is not only insulting, it can also cause him to feel ashamed or afraid because he can’t possibly turn the pain off and bounce right back to a life that’s been annihilated.

5) You extend vague offers of help

You want to help, but you don’t know what to do, so you offer generalized help for the future.

“If you need anything, just call.” “Let me know if you need help.”

Truth: Your friend is overwhelmed and will have a hard time identifying a need or reaching out to ask for help.

6) You talk about how upset YOU are

I’m not talking about sharing in your friend’s sorrow in a connected way. I’m talking about bleeding your unfiltered reactions and emotions about the devastating event onto your friend; or sharing your “honest” discomfort about your friend’s messy emotional state. (Like Sadie did with me).

You sob uncontrollably. Or you say things like: “I haven’t been able to stop crying.” “I know just how you feel.” “This has shattered my world.” “I feel so uncomfortable being around you.”

Truth: Yes, devastating life events affect everyone in a community. You’re probably hurting, too. You do need to find someone to talk to about your feelings. Your painful emotions also need to be expressed and not invalidated or dismissed. But you need to talk to someone besides the griever about your feelings. Pouring your unfiltered emotion onto your grieving friend demands that she take care of you in the midst of her pain. Your need for comfort adds to your friend’s already heavy burden.

***

None of these common attempts at help actually comfort grievers or traumatized people. They suggest fixes for unfixable problems; they minimize or avoid the searing truth of unfathomable pain; and they ultimately abandon grievers at the time when they most need social connection. Which is certainly not what you intend…

You’re Not a Bad Person For Not Knowing What to Do. I’ll Help You.

The true leaders of mankind are always those who are capable of self-reflection. — Carl Jung

I’m not trying to shame you or make you feel bad for reacting to your loved ones’ losses and traumas in these unhelpful ways. It’s biologically natural for your reflexes to move you to act in this manner, especially in a society that offers no other model for responding to horrendous life events.

What I am trying to do is to bring this dynamic into your awareness so that you can choose to respond differently and more helpfully.

While your brain is indeed wired to reflexively respond to your loved one’s distress with the caregiving impulse that seeks to alleviate their pain (as discussed above), your human brain also possesses the unique capacity for self-awareness. When you can step back and become aware of your automatic responses, you have the power to decide whether it’s wise to actually act automatically or not.

It’s out of respect for you that I’m calling your attention to the underlying dynamics that drive your hurtful grief responses, and to what your reflexive actions might be and why they’re hurtful.

Instead of telling you “don’t do these bad things and do these helpful things instead” as if I’m simply teaching you some new rules, I want help you understand your own inner workings. You’ll expand your own emotional intelligence and capacity for feeling when you understand what’s driving your instinctual responses and why you’d choose to respond differently.

With the backdrop of understanding the underlying biological discomfort that drives your impulse to fix your friend’s pain, and the fact that your friend’s distress needs to be borne rather than cured, I’m going to show you what to do instead.

Real Help: Companions in the Darkness

Painful feelings, borne alone, can be unendurable; together with a trusted companion, they can be borne, which is the first and crucial step in their eventual transformation. — Diana Fosha

The nature of what a social human brain needs when it’s in the midst of distress will tell you how to respond to your grieving friend: What a social brain needs when forced to face intense and overwhelming emotions — such as those your friend is experiencing at a time of loss or trauma — is to feel a resonant connection with caring others. We feel that connection when we feel understood.

As difficult as it may be, to truly help your friend you need to learn to become conscious of and to bear your wrenching inability to help, to choicefully set aside your defenses against your helplessness. Then step toward your friend’s suffering.

Allowing your own heart to crack open and then bearing to stand next to your suffering friend with that raw and open heart —bearing witness to the knowledge that the pain must be borne and that nothing will fix it — is the deepest act of love there is.

When you can bear to know at least a fraction of the enormity of your friend’s anguish and still remain present with her, you’ll begin to see that there is nothing to be done. With humbleness, you can empathically resonate with the inconsolable nature of the pain and sit caringly in its midst.

Approaching devastating pain this directly requires courage. You might need your own support to do it. But you’ll find that it’s worth it.

In the humility of accepting your helplessness, you’ll be able to join with your friend in the darkness of the pain that simply is.

In the joining, your friend is no longer isolated, so the darkness is not quite so dark.

In the joining, you as a helpless helper bear some of the weight of the pain, making it a tiny bit easier for your friend to hold.

In the joining, your friend’s pain may become unstuck and begin to move.

***

Being present like this is the best gift you can offer. To expand on this gift, I’ll give you some concrete ways to bring this presence to your friend.

5 Ways to Offer Presence to Your Grieving Friend

Generous listening is powered by curiosity, a virtue we can invite and nurture in ourselves to render it instinctive. It involves a kind of vulnerability — a willingness to be surprised, to let go of assumptions and take in ambiguity. — Krista Tippett

Here are 5 gentle guidelines that can help you offer grievers the kind of companionship that makes their unbearable journey more bearable. More than a list of rules, these guidelines offer you ways of being that can inform each interaction with your grieving friend:

1) Be present with love

Be willing to listen without offering advice. Bear to hear questions that don’t have answers. Develop the capacity to sit through tears, expressions of anger and confusion and hopelessness, and times of numbness, for as long as it takes. Be willing to say, “I don’t know.” Be willing to have your worldview shattered.

It’s okay to show emotion yourself. Tearing up or sharing your sorrow can help your friend feel understood, as long as you maintain your ability to cope with your own emotions, as long as you don’t allow your feelings to escalate to the same level of intensity as your friend’s feelings, and as long as you’re not asking your friend for comfort. If you can be touched by your friend’s experience yet still remain a strong container for her, that’s ideal.

It’s also okay for you to hold hope for your friend’s future, but inside yourself. Your friend will NOT want to hear about how much you believe that he will eventually heal. But within your heart, you can hold a gentle confidence in your friend’s ability to move through the pain and to heal. Buoyed by your own inner confidence, your actions will come through as compassionate and supportive.

2) Familiarize yourself with the nature of grief

When you haven’t experienced intense grief yourself, witnessing the grief process can be frightening and confusing. If you learn about grief, your own fears can be calmed.

I’m not suggesting that you spend hours reading about grief. There’s a lot of misinformation about grief in our society anyway — like the falsity of the 5 stages and all that. But I offer several easy-to-access resources that describe the nature of grief and that debunk common myths our society purports about grief — some interviews, an e-book, some papers. Click here for those resources.

Alternatively, ask your friend if there’s something he’s read about grief that has particularly helped him and take a look at that to understand where he’s coming from.

Grief isn’t static, so your friend’s feelings will shift and change moment-to-moment. When you’re being present and you understand this quality of grief, you’ll be likely to recognize your friend’s cues about when he wants to sit with you in the feelings, and when he wants to be treated like he’s just an old friend you’re having dinner with.

If you become familiar with what grief looks like, you’ll understand what’s happening as you watch your friend make it through her pain. That way, what you see in front of you won’t be so daunting and bewildering. When you’re less afraid, you’ll be able to remain calm and steady as you support your friend.

3) Learn whom to talk to about what

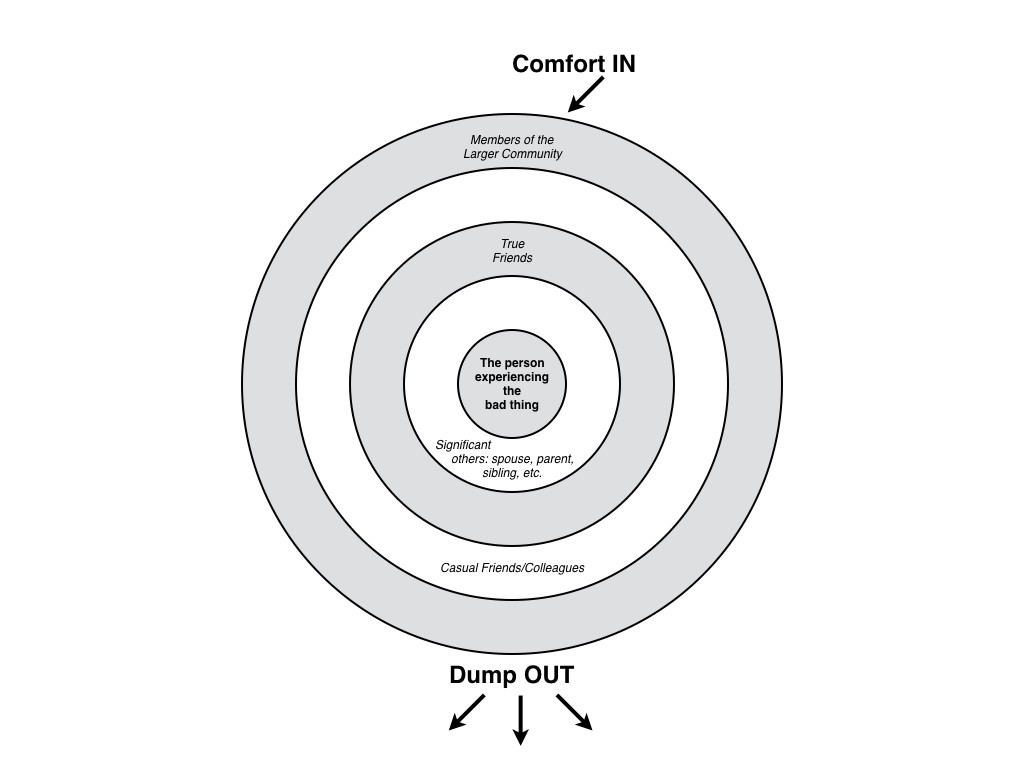

The best resource I’ve ever seen for figuring out “how not to say the wrong thing” to someone who’s going through a terrible time was in a 2013 article in the LA Times by Susan Silk & Barry Goldman. It’s called Ring Theory, and it’s so good I’m going to summarize it here.

Look at this diagram and then read about what to do with it below:

Here are the rules. The person in the center ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can kvetch and complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, “Life is unfair” and “Why me?” That’s the one payoff for being in the center ring.

Everyone else can say those things too, but only to people in larger rings.

When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the center of the crisis, the goal is to … provide comfort and support.

If you want to scream or cry or complain, if you want to tell someone how shocked you are or how icky you feel, or whine about how it reminds you of all the terrible things that have happened to you lately, that’s fine. It’s a perfectly normal response. Just do it to someone in a bigger ring.

The overarching and easy-to-remember rule is Comfort IN / Dump OUT. That is, whenever you’re talking to someone who inhabits a smaller ring than yours, offer presence and comfort; if you need to vent or get help, turn to someone who’s within your own ring or in a larger one.

4) Make the implicit explicit

Sometimes, when you don’t know what to do and you don’t know what to say, when you don’t know if they want to talk about their loss or whether they want to be distracted, the best thing to do is to name what’s going on. (Note: This is NOT the same as blurting out whatever you’re thinking in an unfiltered way, as in the list of unhelpful actions above.)

In a kind and open-ended way, you can say things like:

“I’m so sorry. What you’re going through is so big that I can’t even find words.”

“That sucks. That shouldn’t have happened to you.”

“Sometimes when I get upset my mind goes blank, and that’s what’s happening right now. Please know that I’m here for you even if my words are garbled.”

“I care so much that I don’t know what to say.”

“Trying to say something feels like it would minimize what you’re going through.”

“I feel drawn to give you a hug. Do you want a hug?”

“I’m open to talking about it if you want to. And I’m fine with talking about something else if you want to get your mind off of it.”

Then follow the lead of your friend. Whether they cry, change the subject, hug you, stiffen, say they’re fine, or anything else, let your next step emerge from the cues they give you.

Naming that you don’t know what to say or do, naming that obvious (that the situation is awful), or naming that you’re open to following their lead —all while being open and present — are all better options than saying nothing.

5) Offer specific help (with caveats)

Grievers have a hard time thinking and a lot of difficulty identifying what they need. So instead of offering vague, generalized help like in #5 above, make concrete, specific offers:

“I can come over and walk the dog on weekday mornings.”

“I can bring you dinner next Thursday.”

“I can come over for two hours on Saturday to help you with any tasks that need to be done.”

However, when making these offers, remember these 3 caveats:

- Always ask if it’s okay before you haul off and do something. You don’t want to clean up the kitchen and inadvertently throw out the last candy wrapper the dead spouse left on the counter. And sometimes people need time alone and don’t want someone dropping in with dinner.

- Don’t assume that your friend has suddenly become incompetent or helpless. At times, she’ll need assistance with basics that you’ll be surprised by; at other times she’ll want to do things on her own to remind herself that she’s still alive.

- Making the implicit explicit around offering help can make all this easier, too. Say something like, “I’m offering to do [task x] to help you, but I don’t want to interfere. Please tell me honestly whether you want me to do this or not.” Or, “You may want to do this yourself, but I have time and would be happy to help.”

I hope these guidelines will give you the courage you need for bringing the best of your presence to your grieving friend — with vulnerability and shared humanity.

Bearing to Witness Suffering Heals Us All

To have a compassionate culture, it boils down to two words. It boils down to being able to ask someone, “You OK?” Just the idea that you are acknowledging the possibility that something bad has affected someone, … just really kind of taking a second to inquire in a real way about how someone is doing matters. And even if they don’t tell you, and even if they lie to you, it will probably have a beneficial effect. I mean, what I hear from trauma [and loss] survivors — what I’m always struck with — is how upsetting it is when other people don’t help, or don’t acknowledge, or respond very poorly to needs or distress. … How we behave towards one another individually and in society can really make a very big difference in the effects of environmental events on our molecular biology.— Rachel Yehuda

The key to all help we offer to grieving friends is for us to learn to bear our own unease in the face of the helplessness we feel as caregivers when we witness inconsolable suffering in our loved ones. When we do, we can face the natural caregivers’ anxiety that drives us toward hurtful suggestions for “fixing” inconsolability and choose to respond differently,

When we have the courage to be present and undefended in the midst of our loved ones’ anguish and the helplessness it generates in us, a dark and shimmering beauty emerges.

Softness settles into our eyes when the clouds of innocence are stripped away.

Bearing the unbearable together engenders enlivenment and compassion.

Shared pain moves and breathes.

When we are connected in the utter depths of the human condition, gratitude and appreciation radiate and we sense what it means to be fully alive.

A Free E-Book to Help With Grief:

- If you or someone you care about has experienced a loss, CLICK HERE to download a copy of the FREE e-book Your Grief is Your Own: Dispelling Common Myths About Grief

Originally published at medium.com