by Jill Hufnagel

During a leadership development workshop last week with a diverse group of professionals, a young Black woman asked the white folks on the call to share what they fear as they approach justice, equity, diversity and inclusion (JEDI) work. After a few moments of palpable silence, two white voices offered responses. One white man said, “I’m worried I will get passed over for promotions and opportunities. I wonder if these days I would even be hired. . .” A white woman responded with concerns over her son’s ability to get into a choice college, the very school she attended. While this conversation was tense, it was also telling. It captures a couple of key themes just under the surface when JEDI work moves beyond the low-hanging fruit of quick fixes, listening tours, and unconscious bias training and into the hearts and minds of diverse groups of people facing an uncertain future. If we begin to interrogate deeply the beliefs and assumptions undergirding so many of our systems, we will come face to face with an ugly underbelly we’ve long denied.

“As the rules change, so does our ability to weave our way through the systems we’ve historically architected.”

Two largely unspoken fears threaten to take out even the most thoughtful JEDI interventions. If deep systemic change happens, 1) those of us with the privileges that come with knowing how to traverse myriad systems—from public school and healthcare systems to city councils and corporate America– may find ourselves lost and our compasses suddenly not so accurate and 2) we may discover that our kids don’t inherit the many birthright advantages we’ve freely enjoyed thanks to being white.

Accustomed to walking through life wearing the shield that white skin promises, we become incredibly adept at navigating the systems we work and live in. We know how to build and use connections; we know what to ask for and who to ask; we know where the short cuts are and how to find the shady spots. We speak the language of insiders and expect to be granted entry. Gaining a fairer playing field may well come at a cost. As the rules change, so does our ability to weave our way through the systems we’ve historically architected.

Of all that we amass for our children, and what we aim for them to inherit, privilege is a part of our unspoken, shared succession planning. What, asked that mom who longs for her beloved son’s success, will it take fromus if we collectively invest in a more just and equitable future? Embedded in her fear is a knowing—a knowing that her son’s fair skin has held value that may tank if we begin to extend that same privilege to his darker-skinned peers.

“Privilege is a part of our unspoken, shared succession planning.”

Beneath each of these fears is something more fundamental: an orientation to scarcity. The fires of this orientation are fanned by a fear that is palpable in this politically fraught moment. The idea that there’s not enough, that we’re not enough, that I’m not enough. Pan out from that scarcity orientation and we begin to hear just under the surface that there’s not enough equity to go around; there’s not enough time for the work of justice to take root; there’s not enough trust and safety to have challenging conversations, there’s not enough knowledge to know what to do. As we face the realities of systemic racism personally and organizationally, notice how the prevailing sentiment of scarcity shows up again and again and slinks into the driver’s seat. Scarcity drives us to fear loss rather than embrace possibility. Scarcity’s siren song causes us to rally around our own, to hoard provisions, to seek cover.

“As we face the realities of systemic racism . . . notice how the prevailing sentiment of scarcity shows up again and again.”

What becomes possible if we begin to work, think, connect, experiment, and legislate from a place of abundance? Boards that reflect those they serve; the eradication of homelessness and food insecurity; the elevation of a broad array of voices and in turn unprecedented innovation. To date, change has been incremental. For change to become monumental requires far more of us to own up to and claim our part of the mess.

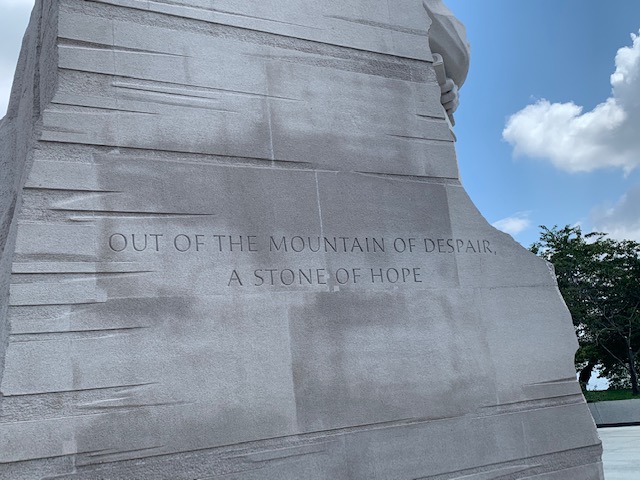

A few days ago, I visited the Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial in Washington, DC. That the only monument in the area to a Black American is placed across Independence Avenue from the city’s monument mecca is telling. Aspirational quotes that capture the humanity MLK called us all into are inscribed along the curved entryways that lead to a massive sculpture of King looking out across the tidal basin.

As I approached the monument, a young Black boy had his arms outstretched, pushing against the stone pedestal holding up MLK. His straining legs braced behind him, his young body believed. He believed that with enough might and energy, he could move that mountain. Chiseled into the mass above the four-year-old boy’s head were MLK’s words: “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.”

If my phone had been in my pocket at that moment, I know I would have taken his picture. I would have taken. I know how to take. Instead, I took in the story he was telling. I inhaled his belief in himself, and in a world of abundance where he was capable of moving marble. In that moment I saw all the ways that together we will take away his naïve belief in himself and in what he’s capable of. I heard what the world of scarcity will tell him about who he is and where he can go and what he can do. I flashed to what we will teach him about his place, how we will chip away at his strength, the ways he must carry himself to survive in a world that is afraid of him. I’m glad I didn’t have my camera. I don’t want to take another picture of loss. The photos of lost brown and black lives papering the chain link fence around the white house tell that story all too well.