A conversation with Kevin Murphy, winner of the MacArthur “Genius” Award and professor of economics at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business, on upward mobility, college loan debt, staggering health care costs, climate change and immigration.

When we think of wealth, we think of money. How rich are you? How many homes, cars and things do you own? How many vacations can you afford to take, and where do you stay? Kevin Murphy, the recipient of the Macarthur “Genius” Award and a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, encourages us to think of wealth in a much more holistic way. He stresses the importance of the family and K-12 education to prepare students to succeed in college and trade school. Murphy quantifies how providing opportunities for the underserved add up to greater prosperity for all of us. He makes a case for the immigrant as a driver of American economic prowess – both high-skilled and low-skilled. He offers guidance on how to spark conservatives to action on climate change.

At a time when upward mobility is backsliding, college loan debt just hit $1.5 trillion, immigrants are under attack and U.S. climate initiatives have been scaled back, a fresh perspective on how to get America back on track, from the expert who studies these things, is something each of us can benefit from. Economists take the politics out of the debate, and focus, rather, on what the historical data tells us about what works and what doesn’t.

Check out highlights from our conversation below.

Natalie Pace: Let’s start with the basics. Why is upward mobility stagnating in America?

Kevin Murphy: In recent decades, the rate of progress has slowed. Most people start their lives with very little in terms of financial wealth. The way that people have done better than their parents is that they were able to achieve more career-wise, in the labor market, than their parents did.

NP: Education is fundamental to getting a better job, right?

KM: Education and skills are more important today than they have ever been.

NP: We have more people entering college than ever. However, only 60% are graduating, and college debt just hit $1.5 trillion. Is this where upward mobility is stalling out?

KM: If you watch late night TV, it’s no longer kitchen gadgets that I remember when I used to watch late night TV. It’s now “Sign up with the University of Phoenix, with Arizona State, with New Hampshire, with the local tech college.” People are going to school. People are trying to get training. However, if you’re not well-prepared, if you didn’t get a lot of quality education and other skills when you were young, it’s very hard to be successful in college. If you want to think about economic mobility, don’t just think about financial wealth. Think about what people inherit from their parents more on the human capital side.

NP: That seems to be a key lesson that is missing from the college admissions scandal. You can’t cheat on tests to gain the skills you need to be successful in life.

KM: Education is a cumulative process. You build on what you already have. When you go to the 2nd grade, you build upon what you learned in the 1st grade. It keeps going on from there. Your success in 1st grade depends a lot upon what you did when you were three, four and five years old because that was the foundation. A lot of people wonder what we’re doing wrong at the college level. I think it’s more about what we are doing wrong before that. Why aren’t students prepared? If they are not prepared, the stakes are high. If they don’t succeed, they’re going to end up dropping out. They are not going to get the skills. And they’re going to end up with a pile of debt. We have to look earlier for the solutions. We’re not doing such a great job of educating a major fraction of our labor force. We also have problems with deterioration of the family.

NP: What role does altruism play in helping the community? Some neighborhoods can easily raise money to fill in the gaps of public education, or send their children to private schools. What does the research show about the commonwealth benefits of helping children in underserved neighborhoods, who are not getting the education in K-12 that they need to succeed in college and trade school?

KM:Our nation got as far as we’ve come by extending opportunities to a broader segment of the underserved population. We wouldn’t have gotten as far as we did, had we not done that. We’re not going to get as far as we could go, if we don’t continue to do that. When some kids in the community start out with poor quality schooling, and have relatively low levels of investment in them, that puts them behind the 8-ball. When they get behind in high school and try to go to college, it is very difficult because they just haven’t developed the skills and foundation they need to succeed. We need to expand the opportunity for the underserved in our neighborhoods, like we have in the past.

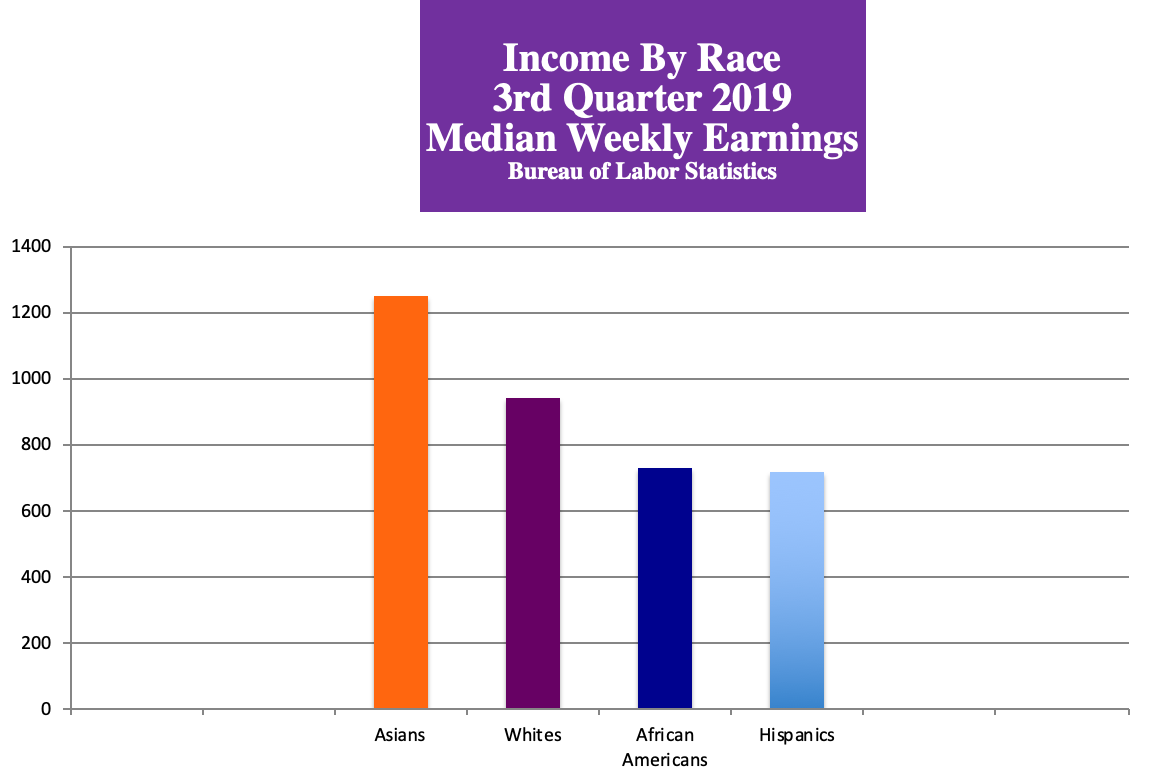

NP: We’ve seen Asians rise to the top of the income-earning demographic in America. In the 19th century, Asians were immigrating to build our railroads at the lowest wages in America, and were even prohibited from immigrating for a decade (in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882). Does the rise in income status to the top of the USA say a lot about their commitment to family and their investment in children?

KM: This does point to the value of the family. You see that same thing among many Hispanic families. Many Hispanics come here and they are very focused on investing in their children. Immigrants are a very big asset. Attracting high-skilled immigrants is a no-brainer. However, low-skilled immigrants are also a great asset because immigrants bring with them a focus on the future. Why would you go to a place where people don’t like you unless you are focused on the future? It’s not a lot of fun to leave your family and friends and go to a place where you are on the outside, where you don’t fit in so well, and maybe you don’t even know the language. People do that because they are focused on improving themselves and the lives of their children. Those are the kinds of people you want.

NP: Immigrants get blamed for taking jobs, but also for draining our health care system and other social benefits. Can we talk a little about health care in America? We spend more on health care than any nation in the world, at $3.5 trillion annually and 18% of GDP. Is this really something we can blame on immigrants, or is there also something fundamentally wrong at play here that is driving up costs?

KM: Life expectancy went up 30 years in the 20th century, which is an enormous improvement, but it has come at an increasing cost. Ultimately, cost containment comes down to having the buyer of the service worry about saving money. We don’t worry about people not having the incentive to build more cost-effective washing machines or toasters or computers. There, where people are spending their own money, there is an emphasis on building things better, but also a strong emphasis on making things cheaper. When people go to the store, they look for a price/quality trade-off. They say, “Well, this TV is $500 and this other TV is better, but it is $3000. I’ll have to go with the $500 TV.” That creates the incentive to make the $500 TV, rather than just make the greatest $3000 TV that you can make.

The markets for plastic surgery look nothing like the markets for other health care. They actually tell you before you go in what the price is. There is a range of prices. You can buy the high-end price, or pay the low-end price. It looks much more like all of the other markets that we’re used to. Why? Because people are spending their own money. When consumers are spending their own money, the markets respond.

That’s part of what we have to move toward – a system where there is more focus on the cost effectiveness of the treatments themselves. This is where the foreign models are not the answer. A lot of those just pay less to providers and suppliers.

NP: Anyone reading this will wonder how consumers can ever pay for their own health care when a trip to the hospital can bankrupt you. That is why so many Americans are paying an arm and a leg on low-deductible health insurance. There are already health savings accounts available that would move toward the consumer weighing in on choice and costs. However, they are not well-known, and health insurance companies have no incentive to sell them, when their own premiums will be cut so dramatically. (Yes folks, you could be saving thousands on your health insurance premiums annually, particularly if you are healthy.)

KM: I think more people would take it if they knew about it. Don’t give up! People have a lot on their minds. They don’t always respond, but just keep pressing. It may take 10 years for people to switch how they run their lives. But, we have to do that. We don’t want to get to a point where we spend 35% of GDP on health care. We need to make these products as attractive as possible to people. The benefits that I’m talking about require people taking it in numbers. If we have a marketplace where more people are weighing in on the price, the supply side of that marketplace will respond.

NP: If more people knew just how underfunded their pensions and other post-employment benefits are at these legacy corporations, they’d be very interested in the Health Savings Accounts. It’s the top of the market. Pensions and benefits are historically overfunded at this stage of the business cycle.

KM: If you think the corporate systems are terrifying, you should look at the state and public systems. They are terrifying squared. People don’t do such a good job of taking care of other people. We have to recognize that. That’s just how people work.

NP: That sounds like

the perfect lead-in, sadly, to talk about climate change. How can we, at long

last, provide the economic incentives for consumers to reduce their carbon

footprint, for corporations to stop offering single-use everything, for the

electric grid to be powered with clean energy and for plastics to be replaced

with something that doesn’t pollute our oceans?

KM: Ultimately, people have to be incentivized

through the prices they pay. You have to raise the price of carbon. If the

buyers can cheaply use less, they’ll do it. If the suppliers can cheaply use

less, they’ll do it.

The bad news behind a carbon tax is that for every dollar of climate benefit that it would generate, it generates a lot of tax dollars. A conservative estimate might be $20 in taxes for every dollar of climate benefit. So now, think about the battle lines in climate change. Does it look like a battle between people who care about their children and people who don’t care about their children? Or does it look like a battle between people who would like a bigger government versus people who want a smaller government? It looks like the second one, not the first one.

People don’t look at this as a choice of climate versus not climate. They look at it as a choice between big government versus small government. If we close the gap politically, we’ll have a much greater chance of success. That’s why I think the Green New Deal is politically a tough way to go. That’s going to run into more resistance than you need to tackle the climate problem.

The question is, “How do we deal with it without pitting the bigger government and smaller government forces against each other?” In principle, you should be able to do that.

MacArthur “Genius” Award winner

University of Chicago Booth School of Business professor

About Kevin M.

Murphy

Kevin

Murphy is the George J. Stigler Distinguished Service Professor Economics at the

University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He is the first

professor at a business school to be chosen as a MacArthur Fellow. He was

selected for “revealing economic forces shaping vital social phenomena

such as wage inequality, unemployment, addiction, medical research, and

economic growth.” In addition to his position at the University of

Chicago, Murphy works as a faculty research associate for the National Bureau

of Economic Research. He primarily studies the empirical analysis of

inequality, unemployment, and relative wages as well as the economics of growth

and development and the economic value of improvements in health and longevity.