Mental illness is now blamed for the outbreak of school shootings wreaking havoc on communities. Far less is discussed about the huge risk for victimization among those with serious mental disorder—or the clear reductions in violence when people with severe mental illness receive evidence-based treatment.

Beyond schizophrenia and psychotic forms of bipolar disorder, mental disorders include the more prevalent conditions of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and ADHD. The opioid epidemic is wreaking havoc around the nation. Suicide rates are rising in all age groups, with suicide now the number-one global cause of death for girls and young women aged 15-20 years.

The mental health crisis is real.

People with the most severe forms—featuring hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia—have limited insight into their conditions. Until recently, it took only a brief report by a psychiatrist, plus a willing judge, to place such individuals in snake-pit public mental facilities, often for the rest of their lives. In the 1960s and 1970s civil rights were extended to “mental patients,” as involuntary commitments were greatly restricted during the deinstitutionalization movement, guided by both humanitarian ideology and cost-containment.

Now, far too many individuals with severe mental illness live under freeways or on Skid Row. Vast numbers crowd underfunded urban jails and prisons. Few, if any, legal means exist to enforce treatments that are desperately needed. The long-term economic cost is huge, as mental health and substance abuse disorders devastate academic performance and job productivity and lower life expectancy by an average of 10-25 years. These conditions result in major financial losses for families, communities, and the country at large, measurable annually by over a trillion dollars worldwide.

Throughout history, mental-health conditions were thought to emanate from evil spirits or weak personal will. Poor parenting was blamed during most of the 20th Century; more recently, ‘bad’ genes have been the culprit. In truth, like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, mental illnesses are shaped by genetic vulnerability as amplified by trauma or serious life stress.

Cures do not yet exist, but evidence-based treatments can greatly facilitate recovery. Yet a 10-year gap exists between the noticing of core symptoms and pursuit of treatment—because of ignorance, shame, poor access to care, or lack of financial resources.

Americans know far more about mental health than 60 years ago, but attitudes have hardly budged since the silent 1950s. In fact, three times more U.S. citizens now believe that mental illness is associated with violence, thanks in part to stereotyped media images. Without access to care, the vicious cycle becomes self-perpetuating.

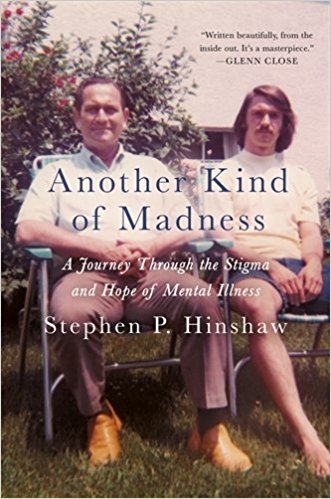

I learned the hard way. Growing up in a warm, academic Midwestern family, I was baffled by my father’s periodic disappearances for up to a year at a time. Unspoken was that he was placed in barbaric mental hospitals for bouts of wild mood swings and irrationality, misdiagnosed as schizophrenia since he was 16, when he jumped from the roof of his family home with the belief that his “flight” would signal the free world to stop the oncoming Nazi threat. Despite his barbaric stays in some of the country’s worst mental facilities, he survived and eventually thrived in his chosen field of philosophy.

When my sister and I were young, during the 1950s, his doctors ordered complete silence, telling him and my mother that disclosing the reason for his disappearances would permanently destroy the children. Would an oncologist tell parents never to disclose cancer to the children? It’s unthinkable. But as for mental illness, the shame was so great that the topic was deemed off limits.

Like most kids in situations of silence, I took on the blame, wondering what I’d done wrong. It wasn’t my first spring break from college that Dad revealed his bouts of chaos amidst his achievements as a philosopher. I became entranced with psychology and soon helped to diagnose him correctly with bipolar disorder. Yet fighting the terror that I might lose my mind and be placed in a mental hospital, I suffered major doubts and real depression. More recently, I’ve become dedicated to reducing the stigma enshrouding the entire topic.

Progress is at hand: People are now discussing mental health more openly. Pursuing therapy is viewed a sign of strength, not weakness, even in the NBA. Yet disclosure of mental disorder can still prevent one from renewing a driver’s license, serving on a jury, or maintaining custody of one’s children.

At the policy level, we must continue to fight for mental health parity and enforce anti-discrimination laws. A far more humanized set of media images is needed. And investing in evidence-based treatments will yield major long-term savings and ease the tragic personal and family-related burden of mental disorders. For each of us, a stance of compassion can fuel our success as a species.

People with mental disorders are not “them”—a deviant, flawed subspecies, but us: our children, our parents, our relatives, our closest contacts, even ourselves. Mental health is one of the last frontiers for human rights. We all lose by remaining silent and allowing stigma to fester.