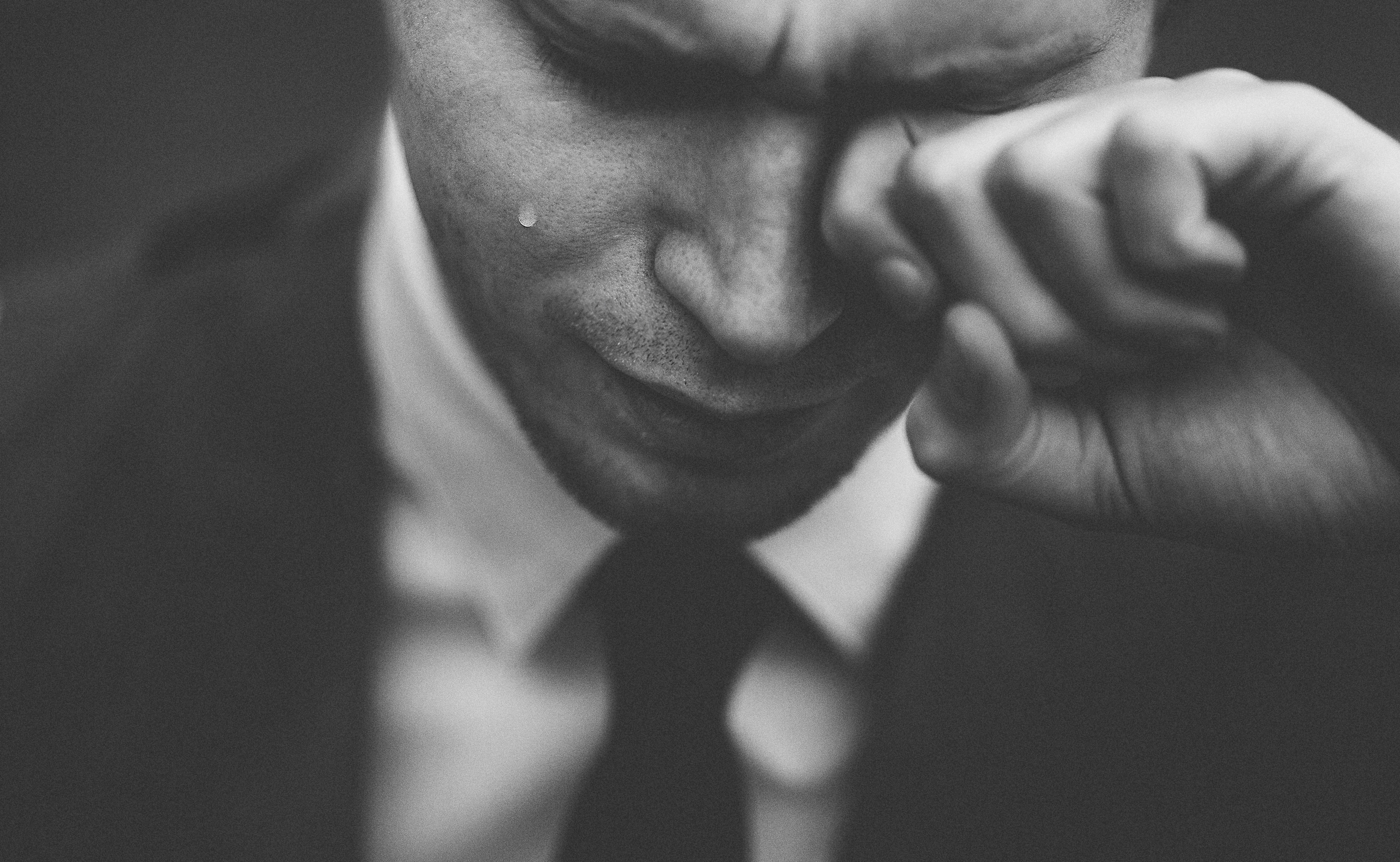

How to spot the signs that employees are hitting a mental brick wall.

We all have down days at work when we find it hard to fire up enthusiasm for our job. But when does that lack of fire turn into burnout – and what can you do if the thought of your workplace leaves you in a blazing depression?

The idea of burnout as a syndrome has been around for decades but has been put into sharper focus by the World Health Organisation, which officially recognised it as an ‘occupational phenomenon’ that needs to be addressed.

The organisation says that burnout is not a medical condition but is emotional exhaustion – a syndrome that results from extreme workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.

Burnout can lead to serious physical, mental and social consequences but it is usually a very slow burn rather than a dramatic, sudden conflagration. So employees – and their employers – have time to spot the symptoms and do something about it.

According to David Ballard, co-editor of The Psychologically Healthy Workplace: Building A Win-Win Environment For Organizations And Employees, job burnout is “an extended period of time where the demands being placed on you exceed the resources you have available to deal with the stressors”.

The WHO says it is characterised by three things – feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance, negativism or cynicism to your job; and reduced professional efficacy.

A 2018 Gallup survey found that nearly 25% of 7,500 full-time employees felt burned out at work most or all of the time with 40% of them feeling burned out at least some of the time. However, a similar study of 1,500 people by the American Psychological Association found that only 8% were experiencing burnout frequently, while a quarter said they had burnout at least some of the time.

Some experts remain sceptical that job burnout is any different than mental wellbeing problems seen in other areas of life. American psychologist Irvin Schonfeld believes what many people call workplace burnout is merely ‘normal’ depression. He argues that workers are avoiding labelling themselves as depressed because of the stigma associated with the condition and that the phrase ‘burnout’ is much more acceptable to an employer.

He says a diagnosis of depression could jeopardise someone’s job. “It’s much easier to say, ‘I’m burned out by my job’ than ‘my job depresses me’,” he adds.

But the intervention of the WHO means that burnout, however you define it, is much more on the radar of employers, who can look out for it in the workplace and act accordingly.

This may be resulting in more reporting of the phenomenon or it may mean more of it is on the rise, as people’s jobs become more stressful in a digitised, multinational world.

According to the Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, burnout is having a growing impact on workplaces, in particular in advanced economies, and cases are reported more frequently at times of economic crisis

“While there are no firm numbers of how prevalent burnout is, some professional bodies report a rise in the reporting of the condition,” says clinical psychologist Dr Russell Thackeray. But he adds: “It may be that the rise is simply the result of the condition itself being recognised.”

So what are the symptoms? Employees may feel burnout when they think they are not making an adequate contribution to their organisation or do not feel their efforts are appreciated; have conflict when it comes to their role; have an overload of work or what is expected of them is not predictable or clear.

Burnout is more likely when an employee expects too much of themselves; never feel that the work they are doing is good enough; feel inadequate or incompetent; feel unappreciated for their work efforts; have unreasonable demands placed upon them or are in roles that are not a good job fit.

“Some people also have burnout following a high point in life when the ‘come down’ after the event arrives,” adds Thackeray. “The ‘next mountain’ can be a challenge when you’re burned out.”

Because burnout can have a devastating effect, hitting the health and performance of employees at all levels of organisations, prevention strategies are considered the most effective approach in addressing it. And one of the first ways to do that is for people – especially managers – to be able to spot the signs.

The majority of employees experiencing burnout stay at work. Being aware of changes in attitudes and energy can help with early identification. Employees may not realise that they are dealing with burnout and may instead believe that they are just struggling to keep up during stressful times. But stress is usually experienced as feeling anxious and having a sense of urgency, while burnout is more commonly experienced as apathy, helplessness or hopelessness.

A worker may be experiencing burnout if they have reduced efficiency and energy; increased frustration; more time spent working with less being accomplished; lowered levels of motivation; increased errors; fatigue, headaches, irritability or suspiciousness.

The employee may also be showing signs of self-medication with alcohol and other substances, sarcasm, negativity, self-doubt, poor physical health or increased absenteeism.

People who have suffered from burnout report that it is a slow journey back to good mental wellbeing and a complete reappraisal of their life was needed before they could start to recuperate.

Recovery takes anywhere from six weeks to two years, with an average of six to nine months. Most sufferers describe recovery as a life-long journey with many benefitting from talk therapy, including group counselling. Medication may also be involved.

Most people make significant life changes around how they take care of themselves and how they think about themselves, how they do their work and how they conduct their relationships.

Self-care strategies include minimising or eliminating alcohol and caffeine; developing and following a healthy eating plan; taking time away from work; ensuring that the recovery process includes the development of a healthy approach to work; exercising or walking in green space and finding a creative outlet, such as painting or gardening.

“The good thing about burnout is that it can be fixed,” says Thackeray. He suggests incorporating meditation, gentle exercise and reconnecting with a sense of fun and laughter in the daily workplace routine. “This combination of renewal approaches works well to manage anxiety and stress management,” he adds.

But while recovery is highly probable, the most effective – and most efficient from an employer’s point of view – way to solve burnout is to stop it from growing in the workforce to start off with.

So what can an employer do to prevent burnout in their employees? Here are some suggested strategies:

- Provide clear expectations for all employees and get confirmation that each employee understands them

- Make sure employees have the necessary resources and skills to meet expectations

- Provide ongoing training to employees to maintain competency

- Help employees understand their value to the organisation and their contributions to the organisation’s goals

- Enforce reasonable work hours, including, if necessary, sending employees home at the end of their regular workday

- Help assess workload for those who feel pressured to remain working beyond normal business hours

- Set reasonable and realistic expectations. Organisations should be clear as to which activities require the highest standards and when it is okay to lower the bar and still meet business needs

- Encourage social support and respect within and among work teams

- Support physical activity throughout the working day

- Strongly encourage the taking of breaks away from the work environment

- Consider how leadership approaches might impact employees at risk of burnout

Certainly, employers need to take the issue of burnout seriously. If an employee is sitting at their desk slowly being less productive, quite apart from the duty of care their company has in looking after them, it may be the bottom line that is suffering, too.