The following is an excerpt from my book, Un-Lonely Planet.

***

It was a chilly Friday night in October, and I had no plans. I was about to text my friend Duncan when, no surprise, I get a group text from the very same man. “Crew!” he said. “Going to see this amazing documentary about a men’s group in Folsom Prison called The Work. Opening weekend. Let’s go support!”

Two hours later and I was sliding into my seat in a half-filled movie theater.

The first moment of the film is a low, guttural chant: “Zim- bah-way.” It’s being bellowed out by James McLeary, a large black man wearing a yarmulke, who stands in the center of a circle of men. Every time he finishes one call, the rest of the group responds with a noise that comes deep from their belly: “Shoo!” The sound sends a chill up my spine.

For the next ninety minutes, I am more gripped by a film than I have ever been in my entire life.

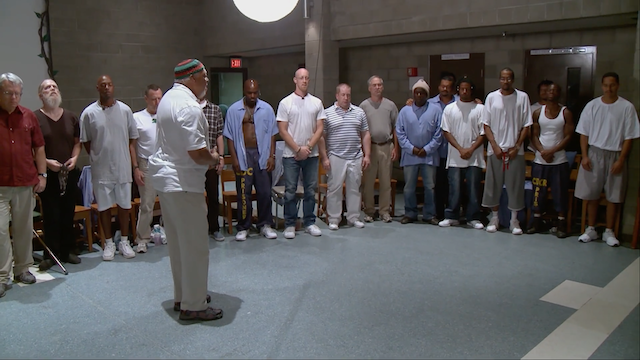

The Work is an inside look at a men’s group inside of Folsom Prison. Half of the participants are prisoners; half are men from the outside. The cameramen sit within the group circles, which gives viewers a painfully intimate look into the process of men who are working through decades of emotions they have been forced to stuff away. As you can imagine, it’s not pretty when the layers begin to peel away.

In one electric moment of the film, a man realizes he’s been holding something in that he needs to say to his dad. Immediately a facilitator asks him to pick someone in the group to serve as a representation. Once chosen, that symbolic father figure stood on the outside of the circle. The rest of the group surrounded the man, asking him what he wanted to say to his father. They pushed the person in the center, telling him that he wasn’t a real man, until his anger finally starts to boil. He begins pushing against the arms of the men and screaming: “Why won’t you spend time with me? Why won’t you spend time with me?” Again and again, he throws himself against a wall of men.

Finally, he collapses. His body relaxes, and a smile crosses his face. Something has been released.

As Gethin, the film’s director, later told me:

“You’ll never feel a container like that one. It’s electric. You can touch it. There’s magic, and it’s hard to put your finger on. Yet I’ve just had too many experiences where I’ve seen a man transform and thought, ‘This is impossible.’ And that kind of change can happen because we really take the time to set the space. We make it safe. There’s poetry. There’s chanting. Plus, the men in prison are really fucking committed. They know this matters, and they only have three or four days. Then they’re done. They’ve got to put their armor back on and go back into the world of Folsom.”

When the credits have rolled and the lights go up, the entire theater is dead silent. My body is covered in goosebumps.

At that moment, some of the crew from the film are there to take questions. One of them is the man who led the chant!

Finally, a woman raises her hand. “Can you do the chant with us?” she asks. “Yes!” I call out, grinning. There’s a pause, and I worry that I offended him. Thankfully, he looks at us both, smiles, and stands taller. “Alright,” he says. “Everyone stand.”

Immediately, the entire theater rises as he calls out the first “Zim-bah-way.” It reverberates throughout the theater. We answer back: “Shoo!” He calls again. We respond. Faster and faster we chant, until he finally puts his hand up, signaling us to stop. The room quiets, and the air feels electric.

Because of that screening, both Duncan and I felt connected to Gethin. We wanted to supported him however we could—and to become his friends. That’s how I ended up sitting with Gethin in a coffee shop, asking him how he got started in the world of men’s work in the first place.

It turns out, Gethin used to think group therapy was bullshit. In fact, when one of his friends invited him to The Mankind Project—a facilitated retreat for men to process emotions and discuss masculinity—he completely ignored him. Yet his friend was determined. Every time he saw Gethin, he would ask, “Have you done it yet?” And every time, for six years, Gethin responded with a “Fuck off!”

Sometime during the seventh year, Gethin couldn’t sleep. He was tossing and turning in bed, staring at the ceiling. Then, out of the blue, a thought popped into his brain: “That Mankind thing my friend keeps telling me about? I need it, and I need it now.”

All Gethin knew about The Mankind Project was that it gave men an initiation ritual into manhood. According to his friend, it helped men leave behind their childhood and step into who they truly are. That used to sound stupid to Gethin. He didn’t understand why diving into childhood wounds would be helpful, or why these guys felt like they weren’t truly in their “manhood.”

But, for some reason, something had shifted in him. He realized something was missing in his life, but he couldn’t figure out what it was. Yet he was confident that he was going to find it through Mankind Project.

The next morning Gethin called his local Mankind Project chapter and found out they were hosting something called “The New Warrior Project” in a little over a week. Without even hesitating, he signed up.

I asked Gethin what he needed from that experience. After pausing for a moment, he said, “I knew I needed to shed something in order to step into manhood. Rituals for that don’t exist in our society anymore.”

Looking back twelve years later, Gethin realized that he started healing from his childhood during that weekend. “I wouldn’t say I had the worst childhood,” he told me. “But there were things I’d picked up along the way that I needed to put down.” He also felt like he tapped back into a sense of inner knowing that he’d lost through the years. “Thanks to The Mankind Project, my inner voice, or my inner intelligence, came back. I’ve learned to trust it and hear what’s right and when I’m faking things.”

Men’s work is so transformative for Gethin that he still goes to a private weekly men’s circle, called an “I group.”

One moment in his years with these men really stands out to Gethin. They were doing some work and something bothered him. “I can’t even remember what it was,” Gethin remembered. “I was just sitting in my chair, kind of rocking.

And I told the guys, ‘I just to want to fall on the floor.’”

With that, one of them looked him dead in the eyes and asked, “So, why don’t you?”

So, surrounded by men who he trusted completely, Gethin got on the ground.

“I just fell on the floor like I was eight years old, feeling terrified,” Gethin said. “In that moment, the little boy in me was feeling unseen and unheld. Something at work had triggered it, and I needed to recognize that. And I needed to let it go. The other men around me just witnessed it, and it felt amazing. That helped me realize and express the part of me that just wanted to curl up and hide because I’d been hurt.”

Gethin told me that his group is like church for him, with a small difference. “The problem with religion is guilt. Original sin. Sometimes I come to group and I’m uncomfortable. I’m in a bad mood. But I show up, and all of me is welcome.”

Resources

- Watch The Work here

- Learn more about Inside Circle, the organization behind The Work

- Learn about The New Warrior Training Adventure