Boredom is getting interesting. Recently, the World Economic Forum has a video about the value of letting your mind do nothing at all:

Take a moment, sit back and just relax. Read more: https://t.co/9U0aLUER72 pic.twitter.com/9pj2ULPFdb

— World Economic Forum (@wef) July 26, 2017

It’s kind of a follow-up to a piece by Silicon Valley author Jordan Rosenfeld about why we should “Learn how to be bored instead” of constantly reaching for our phones during down moments. And don’t expect praise for boredom to disappear: Manoush Zomorodi’s book Bored and Brilliant, based on her radio series of the same name, will be out this fall.

Since writing The Distraction Addiction and Rest, I’ve become more of a fan of taking those moments and just doing nothing at all, staring into space and letting my mind wander. At the very least, such moments give my mind a break from the normal buzz of everyday connected adult life; at their best, they give my mind time to explore new ideas, and even come up with new insights. And it’s not just adults who benefit from this downtime: letting children be bored, giving them the opportunity to exercise their creativity and entertain themselves, turns out to be good for their long-term psychological development (not to mention their parents’ sanity).

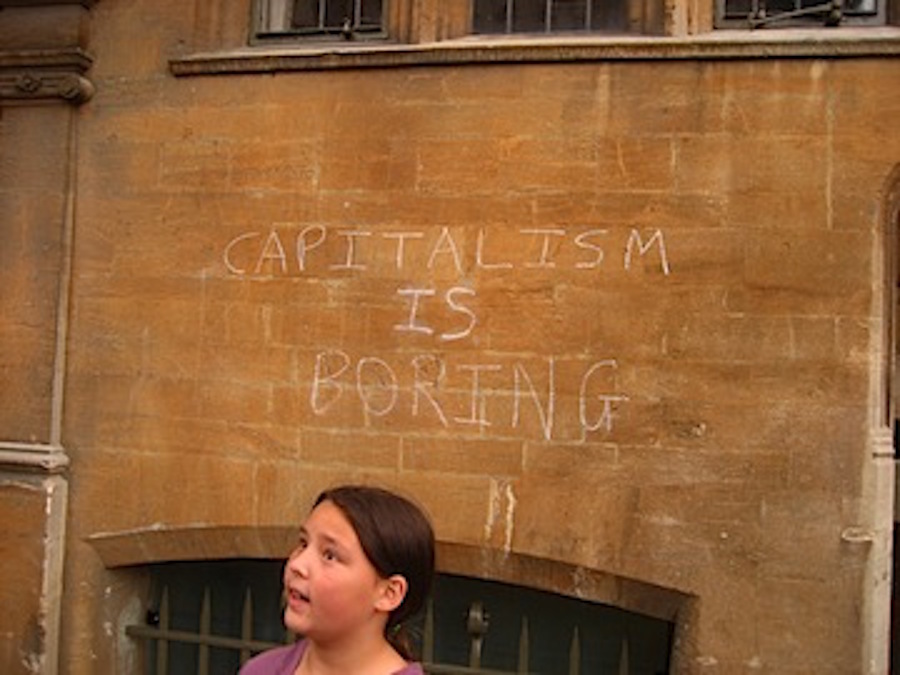

These titles reveal a gap in our language about boredom and downtime. These authors aren’t really advocating “boredom,” per se, but something else: a recognition of the opportunities that those moments when you don’t have to focus on anything provide. Those moments are not merely negative spaces defined by an absence of stimulus, but are positive spaces that should be respected for what they can bring us. The problem is, we don’t have a really good term for them.

I argued in a recent essay in Maria Shriver’s Sunday paper that boredom isn’t a state that’s determined by the world around us. It’s conjured by us. Boredom isn’t like a thermometer that measures how dull our environment is. It’s a more complex reaction of our selves and our surroundings. We might be bored by a movie that we’ve seen many times; we might find a conversation at a reunion dull because our lives and our classmates’ have gone in very different directions; or we might find a place dull because we were dragged there by our stupid parents who think riding around on stupid boats on a stupid river is fun.

The good news is, if boredom isn’t a barometer of how interesting or dull the world is, that means we can control it. We don’t have to treat idle moments as occasions to whip our smartphones. We can recognize that when the world doesn’t offer us stimulation, it’s offering us a gift, not punishment.